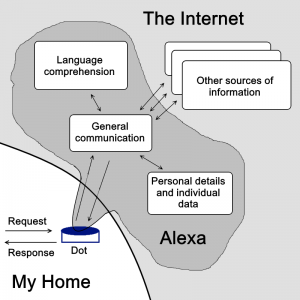

I often think about – and blog about – machine intelligence, both its current state and future possibilities. But artificial intelligence is only one small field of study in a very large and open-ended terrain. News articles on the topic of possible extraterrestrial intelligence are relatively common, even though we have not yet detected anything that can confidently be ascribed to alien sources. Closer to home, we still don’t really understand the spectrum of human intelligence in all its different manifestations, including emotional and social astuteness as well as problem solving and pattern matching.

To add to that, I’ve been reading a fascinating book exploring the various kinds of intelligence seen in the bird world – The Genius of Birds, by Jennifer Ackerman. Perhaps many of us have watched videos of tool-using corvids such as the New Caledonian crows (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cbSu2PXOTOc), or grey parrots demonstrating feats of speech and language comprehension going way beyond simple repetition. But avian intelligence goes well beyond these exploits, which we instantly relate to because they mirror human acts and occupations.

For a long time it was thought that since birds have no cerebral cortex, they were necessarily incapable of reasoning and abstract thought. The cortex appears in the tree of life after mammals and birds parted company. But recently it has become clear that birds simply use a different organ in their brain – the dorsal ventricular ridge, which in fact develops from the same part of the embryonic brain in a bird, that the cortex does in a mammal. The way that neurons cluster, connect, and participate in learning is the same in a bird brain as a mammal. Basically, both the birds and the mammals had to adapt to new circumstances after the natural disaster that killed off the dinosaurs – and they did so using remarkably similar strategies. The different biological frame of the two families disguises many places where a common solution has emerged.

What has this to do with writing? Well, birds can be routinely found in my science fiction stories – I assume that at minimum the more adaptable ones would find ways to survive as we spread out beyond Earth. It’s interesting to speculate which ones will accompany us.

This post is far too short to describe in any detail all the various ways in which birds display intelligence. If you want an overview of that, I recommend the book! But in brief, birds show their intelligence in a variety of ways, just like humans do. There are huge differences between species – corvids are good at problem solving, sparrows and members of the tit family are excellent at group dynamics, chickadees can remember and accurately mimic hundreds of sounds, Arctic terns are prodigiously good at navigation, herons spend considerable time and effort training their young in the art of catching fish. And so on. We tend to notice the exploits of birds which most resemble our own – like crows and parrots – but it’s always worth taking a step back to question our own blind spots. Even the birds we often dismiss as particularly stupid, often have some particular faculty at which they excel.

But as well as variation between species, individual birds of the same kind differ in particular ways. One is bolder, another more cautious. One solves particular problems much more easily than his or her siblings. Again, not very different from human beings.

It’s a sobering thought. Along with a handful of animals, a few birds have found their way into folklore. Odin had his ravens. Several Egyptian and Indian deities have bird emblems or companions. Hawks and eagles have frequently being used as symbols, though more often for their martial prowess than their wits. But by and large, we have rather looked down on birds, especially in the last century or so, imagining that their behaviour was driven purely by instinct rather than rationality. With the cumulative weight of evidence that has emerged over the last few decades, ancient anecdotal tales are metamorphosing into a consistent picture.

So while we’re trying to find intelligence out elsewhere in the galaxy, or to build it with our own hardware and software, let’s also give a thought for the surprisingly clever and adaptable creatures who already share our environment.

As for play? The final video is of a snowboarding crow in Russia (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3dWw9GLcOeA)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3dWw9GLcOeA