So, picking up the story where l left off two weeks ago, it’s time today to look at science fiction set in the near future from its author. Last time the focus was mainly on stories set hundreds of years in the future, where the problem is often that the technology seems pitched at too low a level. But there are different pitfalls with telling a tale in the next couple of generations. Here, an author may well assume that all kinds of things will happen quickly, when in fact they take much longer.

Flying cars are a stock image for a lot of stories, including Back to the Future and Bladerunner. Now, cars have changed in lots of ways over the span of my lifetime, but they don’t fly (and we still don’t have hoverboards). Yes, periodically there are optimistic announcements that they’re in development, but they certainly aren’t normal consumer items. The future bits of Back to the Future are set in 2015, and the original Bladerunner in 2019, so both are very contemporary.

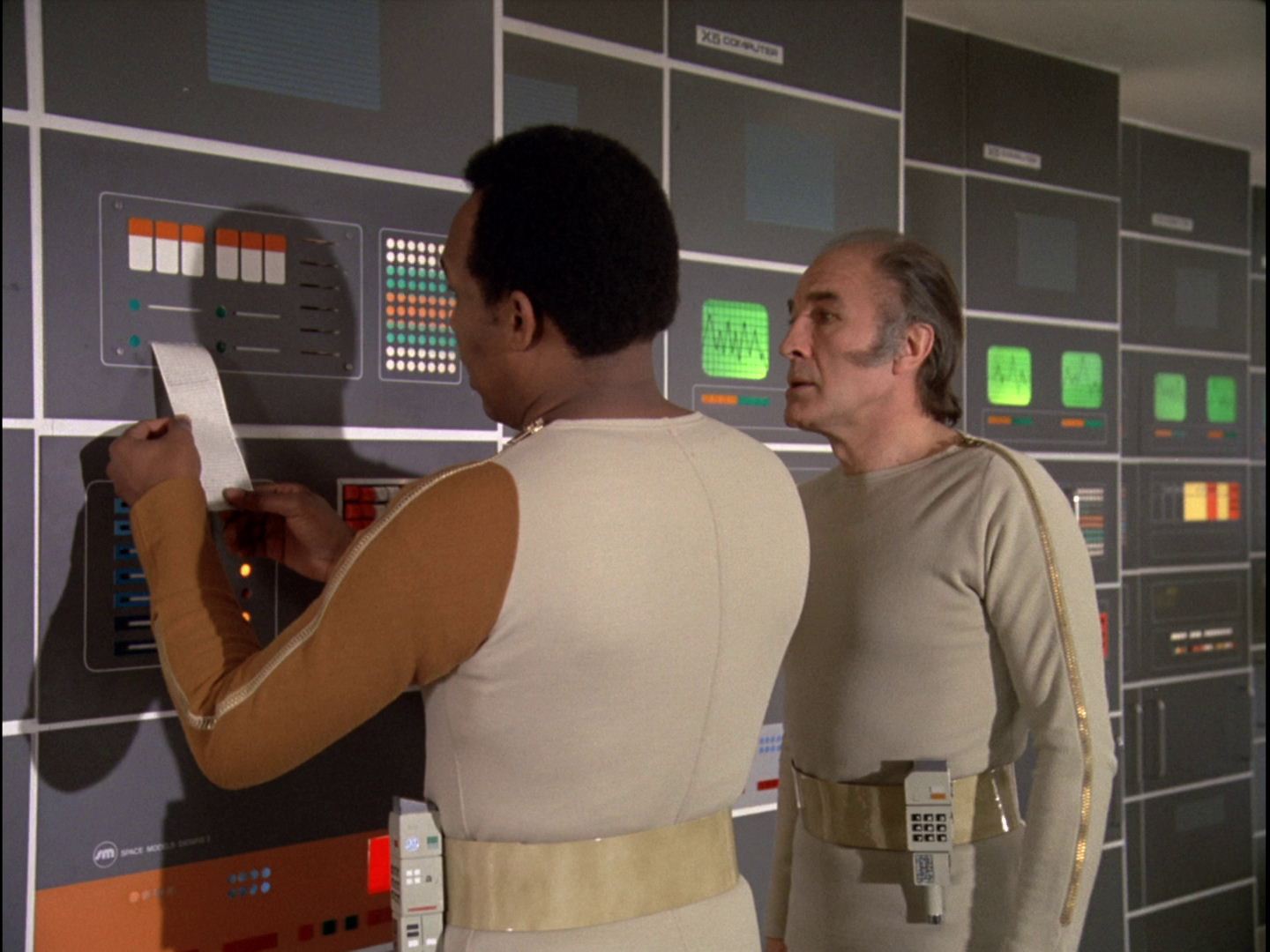

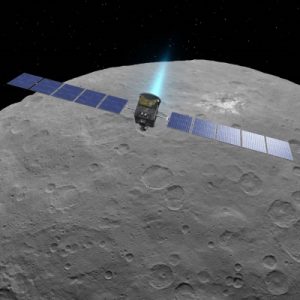

Likewise, lots of science fiction authors assumed that we would have a moon base well before now, and that manned space missions would have visited other places in the solar system. One of my favourite books, Encounter with Tiber, written in 1996, thought it credible we would have a lunar base by around 2020. Space 1999 and the TV series UFO were even more optimistic. The prominence of the ISS, orbiting a mere two or three hundred miles from the Earth, was not often imagined, nor the enormous success of unmanned exploratory probes. Missions like Dawn, to the asteroid belt, or New Horizons, to Pluto and beyond, don’t feature. Still less the Hubble space telescope, or the LIDO gravity wave detector, which spectacularly hit the news this week.

Social change seems profoundly hard to predict. Orwell’s 1984 still has the capacity to grip us with its stark picture of state control, but actually its vision of the future is wrong in all kinds of ways. A great many authors assumed – with good reason – that a third world war would take place in the 20th century. EE (Doc) Smith’s Triplanetary simply had “19–?” as the setting for an atomic missile war, following after “1918” and “1941”. Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep (the short story behind Bladerunner) presupposes a war and heavy resulting pollution behind the drive to spread to other planets, and the construction of android replicants as labourers.

But all of these stories remain worth reading. We often judge the value of a story more for its human drama, and its ability to convincingly present a human response to crisis, than for the accuracy of its timeline. That is as it should be, I think.

I sometimes read criticisms of fiction which focus on the correctness or otherwise of minute details in the text, and sometimes they miss the point. Most of us don’t know the exact terminology of the parts of modern American handguns, and most of us wouldn’t know if the wrong word was used – yes, I read a scathing comment from one reviewer on just this subject a while back. But if the story holds up, most of us don’t mind. Then there’s my own area of expertise – programming. I find it hilarious when expert coders are depicted in films as hammering out on a keyboard at lightning rate without looking at either their hands or the screen. We just don’t work like that. A great deal of time is actually spent in copy-and-paste from geeky sites like StackOverflow (followed by a fair amount of careful reconfiguration). But if the story’s good, I’ll happily overlook that.

There’s certainly a place for research, and good research, in any area of fiction, but not pursued, surely, at the cost of the story and all of its other dimensions alongside the factual ones. So yes – science fiction stories set in the near future often do get things wrong, but often that doesn’t really matter.