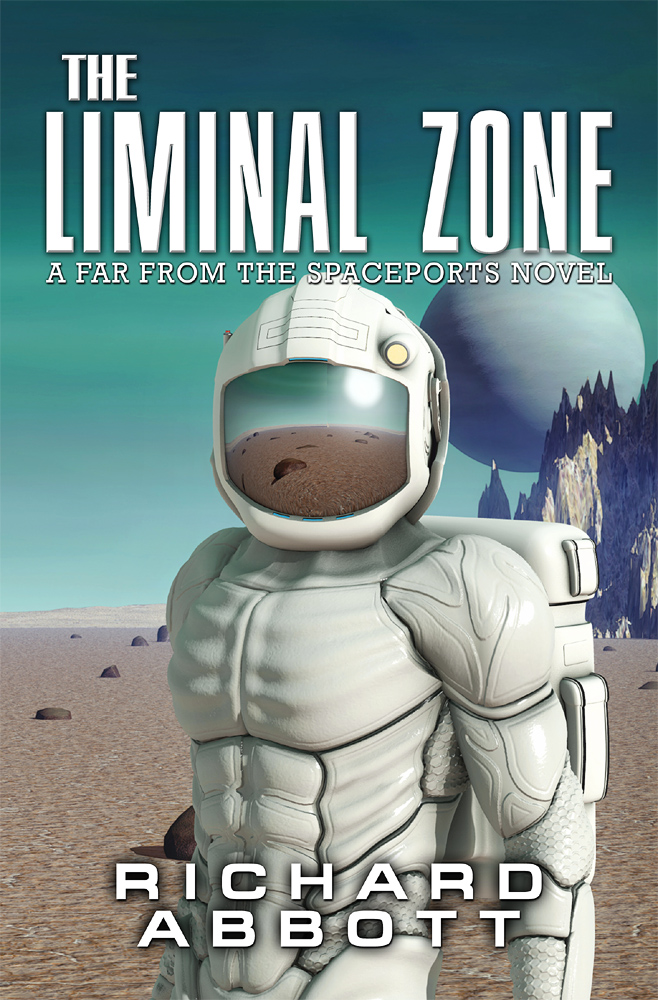

Well, it’s almost time for The Liminal Zone to see the light of day. The publication date of the Kindle version is this Sunday, May 17th, and it can already be preordered on the Amazon site at https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B087JP2GJP. The paperback version will not be too far behind it, depending on the final stages of proofing and such like. I am, naturally, very pleased and excited about this, as it is quite a while since I first planned out the beginnings of the characters, setting and plot. Since that beginning, some parts of my original ideas have changed, but the core has remained pretty much true to that original conception all the way through.

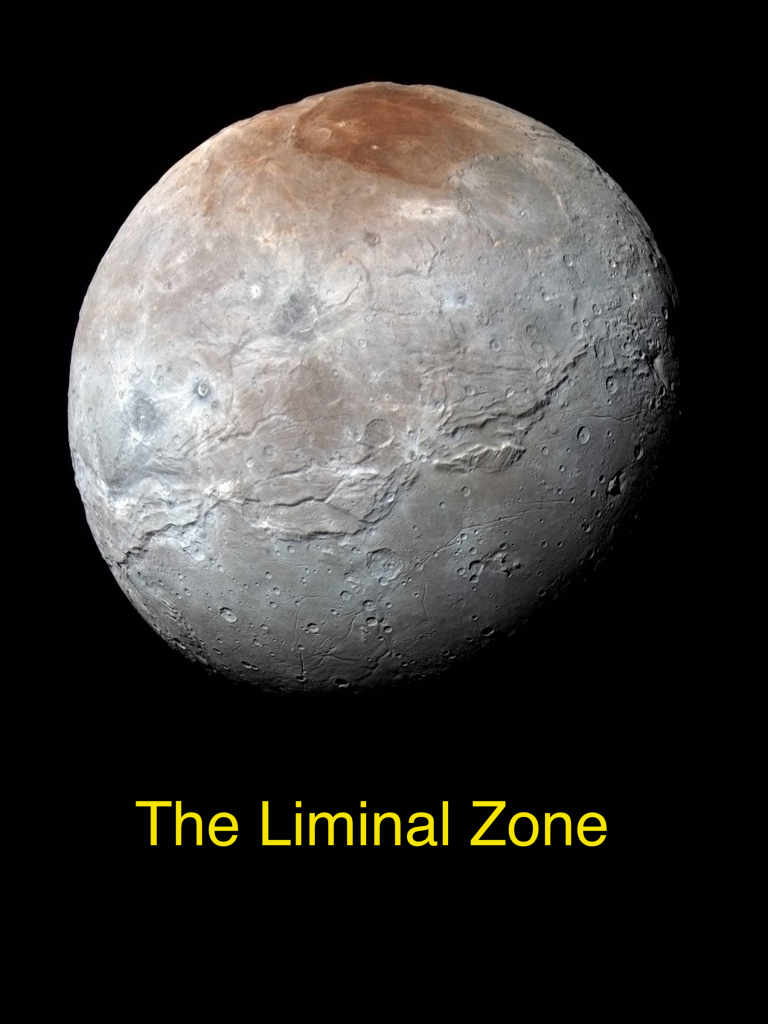

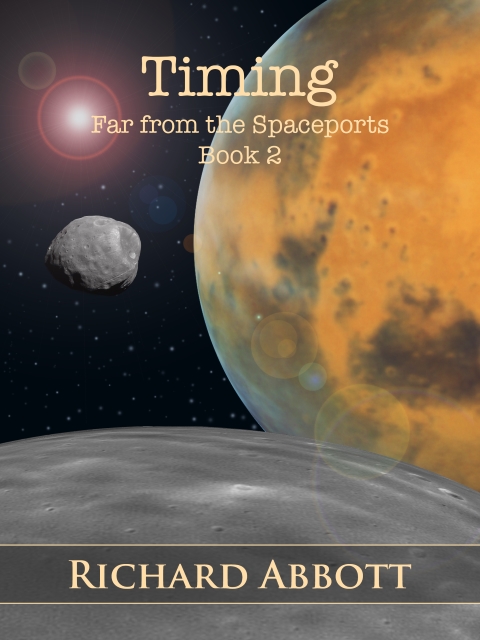

But I thought for today I’d talk a little bit about my particular spin on the future development of the solar system. My time-horizon at the moment is around 50-100 years ahead, not the larger spans which many authors are happy to explore. So readers can expect to recognise the broad outlines of society and technology – it will not have changed so far away from our own as to be incomprehensible. I tend towards the optimistic side of future-looking – I read dystopian novels, but have never yet been tempted to write one myself. I also tend to focus on an individual perspective, rather than dealing with political or large-scale social issues. The future is seen through the lenses of a number of individuals – they usually have interesting or important jobs, but they are never leaders of worlds or armies. They are, typically, experts in their chosen field, and as such encounter all kinds of interesting and unusual situations that warlords and archons might never encounter. The main character of Far from the Spaceports and Timing (and a final novel to come in that trilogy) is Mitnash Thakur, who with his AI partner Slate tackles financial crime. In The Liminal Zone, the central character is Nina Buraca, who works for an organisation broadly like present-day SETI, and so investigates possible signs of extrasolar life.

Far from the Spaceports, and the subsequent novels in the series, are built around a couple of assumptions. One is that artificial intelligence will have advanced to the point where thinking machines – my name for them is personas – can be credible partners and friends to people. They understand and display meaningful and real emotions as well as being able to solve problems. Now, I have worked with AI as a coder in one capacity or another for the last twenty-five years or so, and am very aware that right now we are nowhere near that position. The present-day household systems – Alexa, Siri, Cortana, Bixby, Google Home and so on – are very powerful in their own way, and great fun to work with as a coder… but by no stretch of the imagination are they anything like friends or coworkers. But in fifty, sixty, seventy years? I reckon that’s where we’ll be.

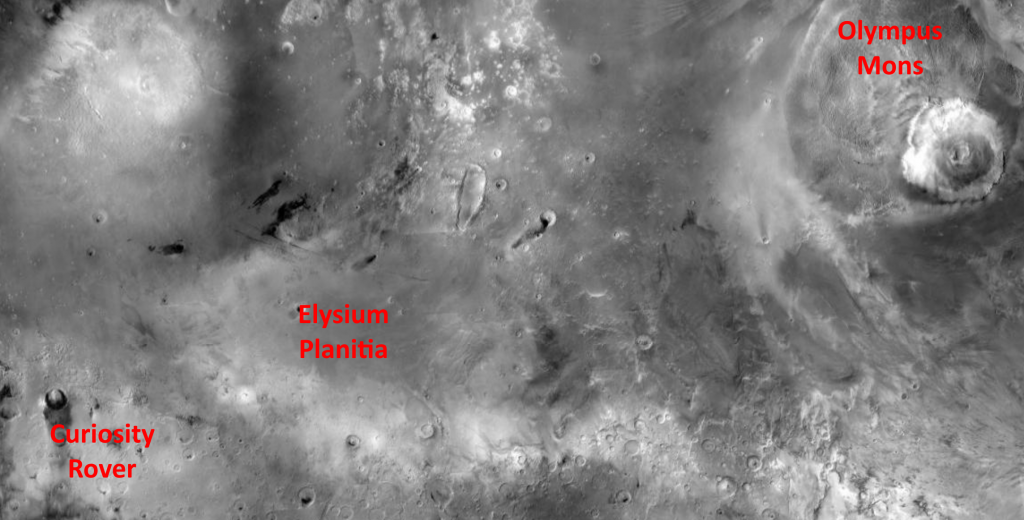

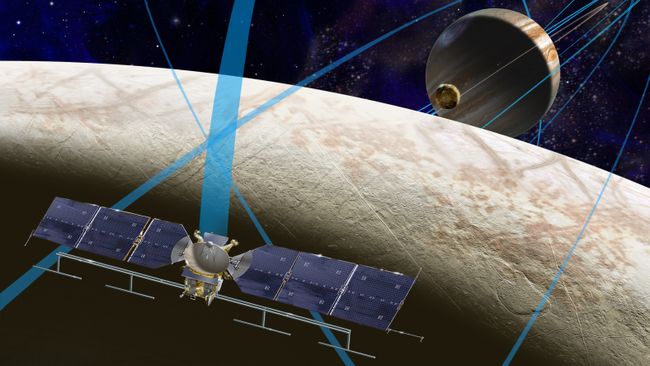

The second major pillar concerns solar system exploration. Within that same timespan, I suggest that there will be habitable outposts scattered widely throughout the system. I tend to call these domes, or habitats, with a great lack of originality. Some are on planets – in particular Mars – while others are on convenient moons or asteroids. Many started as mining enterprises, but have since diversified into more general places to live. For travel between these places to be feasible, I assume that today’s ion drive, used so far in a handful of spacecraft, will become the standard means of propulsion. As NASA says in a rather dry report, “Ion propulsion is even considered to be mission enabling for some cases where sufficient chemical propellant cannot be carried on the spacecraft to accomplish the desired mission.” Indeed. A fairly readable introduction to ion propulsion can be found at this NASA link.

I am sure that well before that century or so look-ahead time, there will have been all kinds of other advances – in medical or biological sciences, for example – but the above two are the cornerstones of my science fiction books to date.

That’s it for today, so I can get back to sorting out the paperback version of The Liminal Zone. To repeat, publication date is Sunday May 17th for the Kindle version, and preorders can be made at https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B087JP2GJP. As a kind of fun bonus, I am putting all my other science fiction and historical fiction books on offer at £0.99 / $0.99 for a week starting on 17th.