Grimspound is a Late Bronze settlement in Devon, in a rather wild and remote part of Dartmoor. I went there years ago – about which more later – but my present focus on it has been because of listening to the track of that name by the prog rock group Big Big Train (it’s on the album of the same name).

Now, my visit to it was with two friends as part of a summer trip down to the west country in the university holidays – a considerable part of the time was spent sampling local ales and ciders, including a particularly memorable evening in Exeter. One of the three of us was studying archaeology, and took us over to Grimspound: a long drive on remote roads followed by a walk of a little over a mile to the ancient monument.

Looking back, this was one of the most significant parts of the whole time away for me – I had been curious, in a vague sort of way, about history before that, but never really about ancient history, or prehistory. The way that my friend talked about Grimspound, and what we know of the culture that spawned it, caught my attention and kindled a fascination for these remote times. That holiday was a very long time ago – over 40 years now – but the fascination has remained with me ever since.

Now, the opening stanza of the song goes:

What shall be left of us?

Which artefacts will stay intact?

For nothing can last

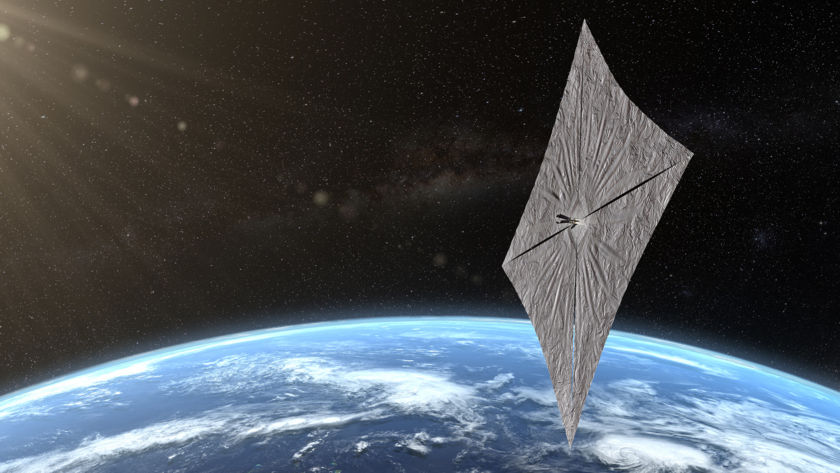

– rather melancholy, perhaps, and the whole song has the feel of a lament. But like so many of the Bronze Age and earlier monuments I see up here in Cumbria, there is a sense of enormous loss. Typically, the places where these sites are found – presumably each a thriving nexus in its time – are desolate and remote, located far from the locations that we prefer in our own age. The adjacent picture is taken on Eskdale Moor, nowadays a vast and empty expanse between Eskdale itself and Wasdale, but back in the Late Bronze a busy spot which has left us numerous enigmatic remains.

Hence the lyrics of the song. Grimspound, White Moss on Eskdale Moor, and a whole host of other similar relics have left us perplexing hints as to a lost culture. These places were thriving settlements, or religious centres, or trading markets, or reminders of political alliances, or… something. We just don’t know what, and the loss of that sense of human activity occasionally weighs very heavily. No doubt at the time they expected that their way of life would be remembered by those who came after, but we have forgotten it, and no longer have any clear understanding of what the stones and their alignments signify. So we too should be asking, what will remain of us?

It’s nice to imagine that in a modern world, with writing commonplace and electronic recording devices readily available, that everything will remain – the dull and dreary along with the exciting. But perhaps not. Even within the electronic age, we have a great deal of information stored in formats, or on storage media, which can no longer be accessed. Go back a few years, and the problems multiply. As some know, I have recently finished walking Hadrian’s Wall – built during an age when writing was reasonably common, and as part of an empire which was at times slightly obsessed with recording minute administrative details. But you cannot walk the wall without becoming aware of how little we know of that structure. What, for example, was the function of the Vallum? There are lots of suggestions, but no consensus. Why did the design specification change between laying the foundations and building the wall? Even – and this is such an obvious thing – how much toing and froing was there from one side to the other on a daily basis? So much of the wall is a riddle, and there are many questions we would love to ask of those who built and lived along it.

If, as I hope and expect, humanity starts to settle on other planets and moons than Earth, I wonder how long it will be before are descendants lose touch with things that we take for granted. It’s something of a trope in science fiction – Isaac Asimov’s books presuppose that the location of Earth is lost, and scholars debate endlessly which of several contenders was the original cradle planet. But I’m not so much talking about the loss of sense of a home planet – it’s more the loss of how life was lived that intrigues me here. I have very little idea how my British forebears of a couple of thousand years ago lived, even with all the artefacts that have survived. Go back another thousand years to the time of Grimspound and Eskdale Moor, and I have vastly less idea. What will remain of us?

Here, for the curious, is the YouTube link to the Big Big Train song (https://youtu.be/Aaf1XDtWVNk)…

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(40)/discogs-images/R-1039597-1196004245.jpeg.jpg)