It’s my pleasure today to be taking part in Helen Hollick’s Christmas Party blog hop. Although this was originally focused on Christmas celebrations, several participants, including me, write about places and times where Christmas is unknown. Scroll to the end of the post for the complete list of participants and blog links.

It’s my pleasure today to be taking part in Helen Hollick’s Christmas Party blog hop. Although this was originally focused on Christmas celebrations, several participants, including me, write about places and times where Christmas is unknown. Scroll to the end of the post for the complete list of participants and blog links.

So after casting about for a few culturally-appropriate festivals, I decided to go with an Ugaritic festival, The Hunt. This is suited to the work-in-progress The Flame Before Us, due to be released early next year.

Of course hunting of itself was a regular part of life in the Levant, and much of the time had no particular religious angle. But it seems, from occasional textual mentions and a certain amount of interpretation of archaeology, that from time to time this ordinary secular pursuit was elevated into a sacred ceremony. The perhaps tenuous connection with Christmas is that here in the UK, there has been for many years a custom for landowners to ride out fox hunting over the Christmas holiday. This is typically regarded as senseless and brutal by city dwellers, but is still popular in many rural areas, where it is seen as an essential part of community life and wildlife husbandry. By law nowadays it has been watered down to a less violent version where foxes do not in fact get killed, and a lure rather than a wild animal is pursued. Such measures would be unthinkable in ancient Ugarit.

One of the Ugaritic texts alluding to this idea of The Hunt is The Birth of the Gracious Gods. In one part of this, the goddesses Athirat and Rahmay go out from the presence of the chief god El in order to hunt. The goddess Anat has a hunting bow which features strongly in some other stories. Gods got involved as well as goddesses – usually what one might call “second tier” rather than centrally important deities. Similar ideas are found in texts from other Bronze Age locations in the Levant and Mesopotamia – and indeed across in ancient Greece a little later.

To appreciate the role of The Hunt, a basic threefold division of terrain must be understood. There are populated settlements – cities, towns, and the daughter villages linked to these. A high proportion of the religious literature which has survived focuses on urban life and urban worship. Around these places was the sown land – not just planted fields, but also pastures for flocks. These were regarded as part of a town’s territory and (by and large) were clear of dangerous predators and wild game. Outside that again was the wilderness. This was the province of the wild things.

Our textual record of religious actions to do with the sown land and the wilderness is scant. We are told of sacred processions which go out from the town into these peripheral areas, lay symbolic claim to them, and then return. And the offerings which are recorded are often typical of the zones concerned – dairy produce or domesticated animals on the one hand, and wild animal sacrifices on the other.

The sacred dimension of The Hunt has to be understood from this perspective. Men went out from their homes into the unknown wild places, and, if skill and divine favour coincided, came back again with bounty. Archaeology loosely supports the idea that The Hunt could have a sacred dimension – we find places where considerable numbers of wild animal bones – deer, gazelle, mountain goat, and so on – are found in clusters around altar sites. In terms of the overall diet, such wild food forms a relatively small component, so these finds suggest that from time to time these animals formed part of religious ceremonies.

It may be important that the law code in the biblical book of Deuteronomy specifically allows slaughter of undomesticated animals outside the system controlled by the priesthood – perhaps recognising not only the food value but also a long-standing custom of informal sacred observance. If so, then the practice seems to have attracted the criticism of later – and generally stricter – generations of priests, and the practice is scarcely mentioned favourably in later books. Perhaps the patriarchal story of Jacob and Esau remembers something of this; Jacob is at home in the domesticated world of the sown land, while his brother Esau delights in the wilderness – The Hunt.

Back at Ugarit, we do not know how often, or by whom, The Hunt was celebrated. In The Flame Before Us, I have taken the narrative liberty of assuming that it was not just for the elite, but a male pursuit shared across a broad social range. This would make it loosely analogous to watching sport today, which cuts right across other measures of status and rank. So here following are a selection of extracts from one strand of The Flame Before Us, scattered through the book.

Tadugari is a high-ranking Ugaritic official, currently a refugee with his wife Anilat and the rest of their family following the sack of their city. Khuratsanitu is a personal guard.

Tadugari is a high-ranking Ugaritic official, currently a refugee with his wife Anilat and the rest of their family following the sack of their city. Khuratsanitu is a personal guard.

Tadugari turned back again to look downhill. Little eddies of onshore breeze stirred the cloud bank, allowed glimpses of the sea beyond the city. At this distance it looked calm, placid. He wore a confused, haggard expression.

“It was to be the hunt tomorrow. One of the king’s own sons wanted me to ride beside him on the chase, and sit beside him at the feast. I won’t be able to do that now. How will I earn his favour again now that I ran away?”

Anilat stared at him in disbelief, and her voice sharpened in anger.

“How can you be thinking of the hunt? My city is ruined. My mother died, and her body was treated vilely before my eyes. My brother and sister are gone, and I have to believe them dead. Out of all this I have my own three children, and my brother’s two. And all you can talk about is missing the hunt?”

He hunched down under the torrent of words and said nothing. She looked around in exasperation. The hillsides around the hut were empty and desolate, and the west was shrouded and gloomy. It was a bitter place.

…

…

Ahead of them Anilat could hear the two men talking. Tadugari was once again lamenting the hunt that he would not be able to join. Her thoughts filled briefly with a burning rage: was there nothing else to talk about?

To her surprise, though, it seemed that Khuratsanitu had also been a regular participant. The common soldiers apparently had their own part in it alongside the nobility, and all shared alike in the drinking afterwards, regardless of rank. The anxiety that had been building within her for several days suddenly burst out.

…

…

[“Should we not stay in Shalem rather than go on further?”]

“The Mitsriy land is good. But the journey to reach it can be desolate and harsh, depending which way we choose. I hope it does not come to that; better by far to find that Shalem is the safe harbour that we have been looking for all this time.”

“Sir, look, they still have the hunt in the Kinahny lands. You have often spoken of how you missed it: you could enjoy it again here. I do not think the Mitsriy have it, though. I hear they snare fish and birds, rather than hunt wild beasts.”

“Their great kings boast of the hunt. But I have not heard that others in their land go out like that. But see, you and I could enjoy it together again: it would not be me alone.”

“Then, sir, would it be so bad to stay among the Kinahny? Their ways are more like ours than those of the Mitsriy. You would find a place among the nobility here; I could serve with their guardsmen. Should we stop here rather than continue south? Surely it is a long way yet if we kept going.”

Other participants are listed below… please follow the links and check them out! Please note also that some items may not be accessible until Saturday 20th December so be patient.. there is some great holiday reading here.

Thank you for joining our party now follow on to the next enjoyable entertainment…

1. Helen Hollick : “You are Cordially Invited to a Ball” (plus a giveaway prize) – http://tinyurl.com/nsodv78

2. Alison Morton : “Saturnalia surprise – a winter party tale” (plus a giveaway prize) – http://tinyurl.com/op8fz57

3. Andrea Zuvich : No Christmas For You! The Holiday Under Cromwell – http://tinyurl.com/pb9fh3m

4. Ann Swinfen : Christmas 1586 – Burbage’s Company of Players Celebrates – http://annswinfen.com/2014/12/christmas-party/

5. Anna Belfrage : All I want for Christmas – http://tinyurl.com/okycz3o

6. Carol Cooper : How To Be A Party Animal – http://wp.me/p3uiuG-Mn

7. Clare Flynn : A German American Christmas – http://tinyurl.com/mmbxh3r

8. Debbie Young : Good Christmas Housekeeping (plus a giveaway prize) – http://tinyurl.com/mbnlmy2

9. Derek Birks : The Lord of Misrule – A Medieval Christmas Recipe for Trouble – http://wp.me/p3hedh-3f

10. Edward James : An Accidental Virgin and An Uninvited Guest – http://tinyurl.com/o3vowum and – http://tinyurl.com/lwvrxnx

11. Fenella J. Miller : Christmas on the Home front (plus a giveaway prize) – http://tinyurl.com/leqddlq

12. J. L. Oakley : Christmas Time in the Mountains 1907 (plus a giveaway prize) – http://bit.ly/1v3uRYy

13. Jude Knight : Christmas at Avery Hall in the Year of Our Lord 1804 – http://wp.me/p58yDd-az

14. Julian Stockwin: Join the Party – http://tinyurl.com/n8xk946

15. Juliet Greenwood : Christmas 1914 on the Home Front (plus a giveaway) – http://tinyurl.com/q6e9vnp

16. Lauren Johnson : “Farewell Advent, Christmas is come” – Early Tudor Festive Feasts – http://wp.me/p1aZWT-ei

17. Lucienne Boyce : A Victory Celebration – http://tinyurl.com/ovl4sus

18. Nancy Bilyeau : Christmas After the Priory (plus a giveaway prize) – http://tinyurl.com/p52q7gl

19. Nicola Moxey : The Feast of the Epiphany, 1182 – http://tinyurl.com/qbkj6b9

20. Peter St John: Dummy’s Birthday – http://tinyurl.com/nsqedvv

21. Regina Jeffers : Celebrating a Regency Christmas (plus a giveaway prize) – http://tinyurl.com/pt2yvzs

22. Richard Abbott : The Hunt – Feasting at Ugarit – http://bit.ly/1wSK2b5

23. Saralee Etter : Christmas Pudding — Part of the Christmas Feast – http://tinyurl.com/lyd4d7b

24. Stephen Oram : Living in your dystopia: you need a festival of enhancement… (plus a giveaway prize) – http://wp.me/p4lRC7-aG

25. Suzanne Adair :The British Legion Parties Down for Yule 1780 (plus a giveaway prize) – http://bit.ly/1r9qnUZ

26. Lindsay Downs : O Christmas Tree, O Christmas Tree – http://lindsaydowns-romanceauthor.weebly.com/

Thank you for joining us – please read, enjoy, and leave comments to encourage all the participants!

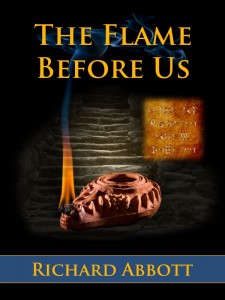

So, the cover piece today is the third individual element of the whole, being an oil lamp nicely lit. Ian and I had a lot of fun tracking down a suitable lamp and working out how to get a good flame with olive oil. Other than being manufactured within the last year or so, this is a pretty good match to an oil lamp of the era described in the story.

So, the cover piece today is the third individual element of the whole, being an oil lamp nicely lit. Ian and I had a lot of fun tracking down a suitable lamp and working out how to get a good flame with olive oil. Other than being manufactured within the last year or so, this is a pretty good match to an oil lamp of the era described in the story. Today I want to look at one specific kind of writing – cuneiform tablets. These are usually surprisingly small, and incredibly densely packed with information. One wonders how, in dim light, it was possible to read the contents at any speed. One’s expectation is that the surface will be rough like a brick, but (unless the tablet has been physically damaged over the years) the surface is typically surprisingly smooth.

Today I want to look at one specific kind of writing – cuneiform tablets. These are usually surprisingly small, and incredibly densely packed with information. One wonders how, in dim light, it was possible to read the contents at any speed. One’s expectation is that the surface will be rough like a brick, but (unless the tablet has been physically damaged over the years) the surface is typically surprisingly smooth. The most common cuneiform tablet is written using the Akkadian script – a character set where a symbol represents a syllable rather than a single letter. Akkadian was used as an international written form for well over 2 millennia, and on a smaller scale for nearly 3. It was used by different scribes to capture several different spoken languages – exactly like modern English letters are used today – so today’s reader of the tablet has to not only decipher the syllabic signs, but then identify the specific language being used. Another form of cuneiform, using the same technology to produce tablets, is found in Ugarit, on the Syrian coast. Ugaritic employs a smaller sign-list representing a true alphabet, closely related to modern Arabic but of course visually quite different.

The most common cuneiform tablet is written using the Akkadian script – a character set where a symbol represents a syllable rather than a single letter. Akkadian was used as an international written form for well over 2 millennia, and on a smaller scale for nearly 3. It was used by different scribes to capture several different spoken languages – exactly like modern English letters are used today – so today’s reader of the tablet has to not only decipher the syllabic signs, but then identify the specific language being used. Another form of cuneiform, using the same technology to produce tablets, is found in Ugarit, on the Syrian coast. Ugaritic employs a smaller sign-list representing a true alphabet, closely related to modern Arabic but of course visually quite different.

Tadugari is a high-ranking Ugaritic official, currently a refugee with his wife Anilat and the rest of their family following the sack of their city. Khuratsanitu is a personal guard.

Tadugari is a high-ranking Ugaritic official, currently a refugee with his wife Anilat and the rest of their family following the sack of their city. Khuratsanitu is a personal guard. I guess what has remained the biggest disappointment for me in Ursula LeGuin’s words is the sense of establishmentarianism in them. She persevered at writing kinds of literature which were, in the early days, not reckoned to be “proper” genres at all. Now they are accepted, and she herself has been accepted – which is fantastic. But does that then mean that the establishment becomes the norm? Perhaps all it has done is tried to absorb what was – and hopefully still is – a voice of dissent.

I guess what has remained the biggest disappointment for me in Ursula LeGuin’s words is the sense of establishmentarianism in them. She persevered at writing kinds of literature which were, in the early days, not reckoned to be “proper” genres at all. Now they are accepted, and she herself has been accepted – which is fantastic. But does that then mean that the establishment becomes the norm? Perhaps all it has done is tried to absorb what was – and hopefully still is – a voice of dissent. The Summer Queen follows the life of Eleanor of Aquitaine (Alienor here, a more accurate representation of the name) up to the point where she is about to arrive in England as the new queen of this land. She is already a highly travelled and shrewd ruler of her own territory and others, and the expectation is set in the reader that things are on the up, after some unpleasant experiences in the first part of her life.

The Summer Queen follows the life of Eleanor of Aquitaine (Alienor here, a more accurate representation of the name) up to the point where she is about to arrive in England as the new queen of this land. She is already a highly travelled and shrewd ruler of her own territory and others, and the expectation is set in the reader that things are on the up, after some unpleasant experiences in the first part of her life.