Last week’s blog post, all about alcohol and law, triggered a number of interesting discussions, and one of them (from a Goodreads friend) has inspired this post. It all started with my brief comment about the prospects of brewing on the ISS, up in the microgravity of low earth orbit. But before we get into space, let’s think about what happens during fermentation. (I’m going to mostly focus on beer in this post but similar comments could probably be made about wine).

People have been brewing beer for many thousands of years – in Egypt the process was well-organised long before 2000BC, and the earliest confirmed evidence for beer-making that I am aware of is from the 5th millennium BC, at Godan Tepe in modern Iran. I strongly suspect the history is much longer, and that more evidence will turn up in time.

Beer making has been credited with all kinds of benefits to humanity, including driving an early wave of technological development. Quite apart from the enjoyment factor. Back then, and for a great many years subsequently, beer was made in open fermentation vessels – basically very large pottery containers, semi-porous and so holding on to residues of yeast and the like. It was often a spin-off of the bread-making industry, seeing as how you needed yeasts and grains for both. Both bread- and beer-making have had, at times, vaguely magical or alchemical associations – these very ordinary foodstuffs are hidden away in a very ordinary vessel, and over the course of a few days they transform into something quite extraordinary. In early times, hops were not added (this seems to have been introduced in the middle ages), but people did sometimes add other flavourings such as fruit or spice extracts.

Now, during fermentation the yeasts work with the various sugars in the raw mixture, together with oxygen in the air at the top surface, and convert these into alcohol and CO2. The process is self-limiting – yeasts eventually kill themselves in too high a proportion of alcohol, so fermentation slows and stops. A brewer can choose whether to let the process go on to completion, or stop it early. An early finish means lower abv (alcohol by volume… the strength of the brew) and a sweeter drink. In olden days, I suspect brewers had conventions about how many days to leave the mixture – nowadays brewers have a more mathematical set of targets to do with final abv balanced against taste. Also, large breweries are very interested in keeping consecutive batches consistent about strength and flavour, whereas a domestic brewer, or someone in pre-industrial days, was less bothered about this.

Finally, carbonation. If you are brewing in an open-top vessel, all the CO2 generated simply goes out into the air. And if you are brewing at room temperature, especially in a hot climate like Egypt, not much gas is held in the liquid anyway. Nowadays we brew and store beer at specific temperatures in order to achieve a target level of carbonation. The colder the beer, the more gas it can retain, and then release as the drinker opens it up at room temperature. You brew for the preferences of your target market – lots of fizz (as in many lagers) or hardly any (as in many real ales).

That brings us onto the specific issue that triggered these fine discussions. What happens in low gravity? Not a problem in ancient Egypt, but looking ahead it’s an issue we will want to solve. Consider a modern fermentation vessel – a cylinder, usually with a cone at the base, and considerably taller than a person. As yeast ferments here on earth, different groups of yeasts arrange themselves at different levels in the vessel – some near the top and others near the bottom. This reflects slightly different ways in which they turn the sugars into alcohol… the sugar level varies in a gradient as you go up and down the vessel. As the yeast becomes exhausted, and starts to die because of the alcohol percentage, the yeast particles sink into the cone, taking with them some of the other residues like hops, grain particles and so on. The beer slowly clarifies by itself, though most brewers also use specific methods to end up with a clear rather than cloudy beer.

That’s fine here on Earth… but in orbit several problems arise. First, there is no real sense of up and down. So a yeast that is used to being near the top of a vessel, with its preferred environment of sugars and whatever, does not know where to go. Likewise, as they finish their job and die from overindulgence in alcohol, there is no “down” direction into which they can settle. Finally, there’s no particular reason why the liquid would stay in one clump – you could easily end up with several disjoint blobs of liquid, with varying proportions of the yeast you had added, each fermenting to different extents.

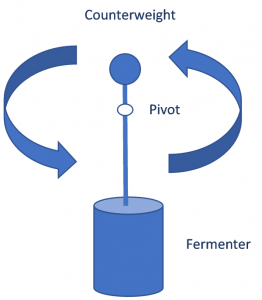

So this was the point I got to in my Goodreads discussion, which triggered several follow-up chats here in Grasmere. Not that we’re (yet) planing on an orbital version of our various beers and ales, but it is good to be ready for the future! The best answer we could come up with was to artificially introduce a sense of up and down by means of a kind of slow-speed centrifuge. Not so fast as to drive all the solid matter to the outside too quickly, seeing as you need it spread through the liquid at first, but fast enough that the liquid stays in one body, and the yeast can tell which tell which way is up and down. (As a side issue, you’d probably want two of these, rotating in opposite directions, so as not to off-balance the space station itself).

The fermentation will generate CO2, and you don’t want to just dump that into the cabin air supply, so you capture that with a safety valve coming out along the spindle (the “top” of the vessel). That can then either be kept for later use – as many breweries fixed here on Earth do, so as to reuse a resource which costs real money – or fed slowly back into whatever air-purification system takes your fancy. When the time comes to clarify your beer, you just spin the centrifuge faster and let the solid particles accumulate in the “bottom”, taking the splendidly clear beverage out of the “top”.

Bottling would be an interesting task, since yet again it is something that here on Earth relies on gravity as well as some back-pressure to get the liquid where you want it to go. But if you’ve successfully got this far, I’m sure that the final stage of getting your finished beer into some kind of container would not be an insuperable problem. In orbit you want low carbonation anyway – the last thing you want is for some rogue container to fob frothy mix all around the interior of your capsule. So you keep the whole thing chilled, to hold the gas in suspension in the liquid, and in any case you aim for a quiet liquid rather than a lively one! And voila – you have Orbital Beer, and happy astronauts…

As mentioned very briefly in Far from the Spaceports, concerning the legendary Frag Rockers bar,

“You’ll need to go to Frag Rockers to get anything decent. Regular fermentation goes weird in low gravity. But Glyndwr has got some method for doing it right. He won’t tell anyone what.”

For the curious, here is a British Museum video of recreating an ancient beer-making process based on what we know of ancient Egypt…