The third and last of this short series on orbits was inspired by a Chinese science fiction film I have been watching on Netflix, together with an analysis I read of the science proposed. The film is The Wandering Earth, and is based on a novella by Liu Cixin, who is perhaps better known as the author of the splendid book The Three-Body Problem. Chinese science fiction is interesting to read – of course it is based on the same sorts of postulated scientific breakthroughs as European or American books, but the perception of recent history is very different, as is the kind of future society that we might expect to live in. There is an assumption that international cooperation will happen naturally in a crisis, led by Chinese technology and expertise. It’s a refreshing change (for a European) than the typical assumption many American authors make, that a world government would be bound to be based on American soil and largely staffed by US citizens!

Now, The Wandering Earth is set some forty years in the future, in which the sun is rapidly expanding, and humans are forced to try to migrate the entire planet Earth to a new home in the neighbouring star system, Alpha Centauri. The entire journey is expected to take something like 2500 years. It’s a bold twist on the idea of the generation ship, in which a group of a few hundred or thousand individuals live on board a large but conventional spaceship, expecting to pass through many generations before arriving at their destination. Here, the ship is the whole planet, and the hopeful survivors are numbered in billions. To achieve this, the Earth is equipped with a huge number of fusion-powered thrusters which slowly propel the planet away from our sun. The crisis of the film occurs as they attempt to use the gravity of the planet Jupiter as a slingshot to get more speed.

Now, the basic scenario of the sun expanding is not actually expected to occur for another five billion years or so, so a forty year time horizon is a bit crazy… but it does allow us to witness near-contemporary technology and human attitudes at work in a crisis, and I am enthusiastic about books set in this near time horizon! But could the thruster idea actually work? Could the Earth’s orbit be altered by such a means?

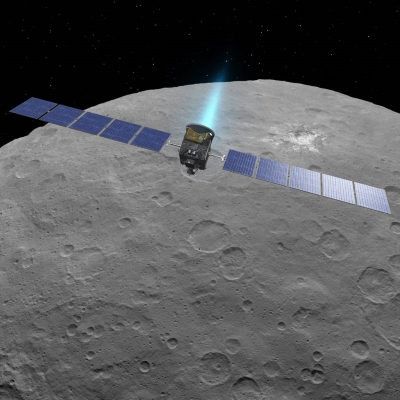

The perennial threat of a meteor or asteroid on collision course with Earth has triggered a few suggestions as to how we would shift the orbit of that incoming body. A large bomb, for example, or a long series of smaller ones, detonated on the surface of the meteor so as to deflect irts course. These methods only really work on something that is small to start with, and any explosion large enough to shift the Earth’s orbit is probably going to do something catastrophic to the land, sea, atmosphere, or all of them together! So we can forget that one, or similar (but less explosive) variations such as docking a spaceship and pushing the body to one side using the main engines.

You could imagine launching a long series of rockets all from (roughly) the same place, which would tend to push the Earth in the opposite direction. And they would also carry up material from the Earth in the form of body and fuel weight. If you wanted to get our Earth to the orbit of Mars doing this, you’d use up around 85% of the Earth’s mass to do so – in other words you would get there, but with only 15% of the planet left. Doesn’t sound appealing.

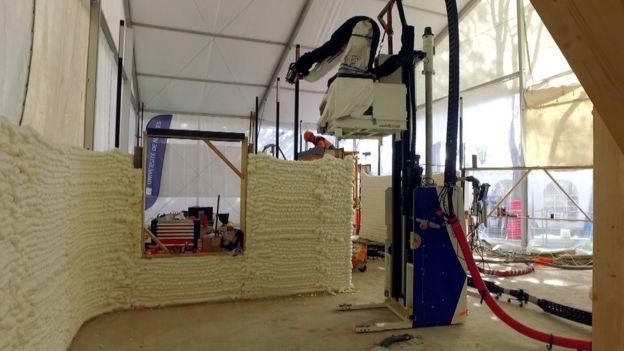

A more effective solution is an ion drive thruster (which I am keen on for other reasons as well, and which features in my own science fiction series). This, indeed, is the solution adopted in The Wandering Earth – large thruster drives are located on the Earth’s surface at major cities, while the population move underground to keep warm and avoid pollution. You keep more of the Earth’s native material this way – getting to Mars only uses up 13% of the Earth. Indeed, lots of the outdoor shots in the film show colossal excavation and earth-moving machinery tirelessly at work to feed the engines.

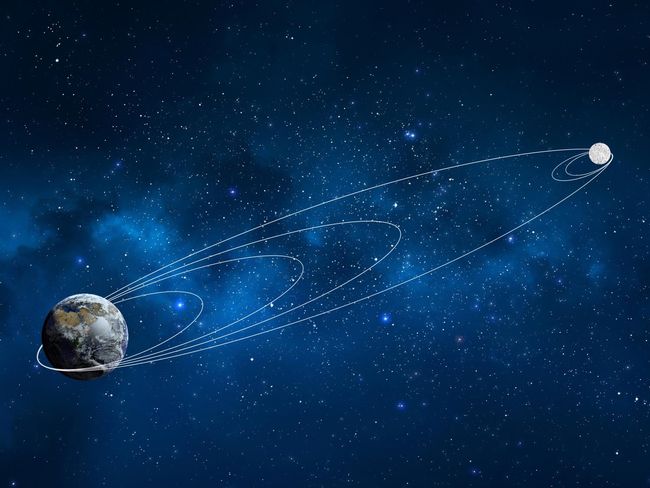

To avoid swallowing up the Earth as fuel, you have to use some external source. Two come to mind. The first is the light of the sun,. captured with some sort of mirror or solar sail. It’s slow, but you could achieve the desired effect in about a billion years. Not good enough for the film’s plot, but actually it would easily suffice for the real situation our remote descendants will need to tackle. The second is to exploit the huge amount of matter drifting around our solar system in the form of asteroids, and deflect these into new orbits which graze past our Earth. As they do this, the same slingshot effect that we normally use to accelerate small spacecraft can be exploited to move the Earth. Each interaction achieves a minuscule change, but a huge number of them eventually gets the job done. Of course, you’d have to have extreme trust in the orbital calculations, since the method relies totally on getting this long stream of asteroids as close as possible to the Earth without actually colliding with us! This, bizarre as it sounds, seems to be the most effective way to solve the problem. Each asteroid or comet can be used multiple times (until their own orbit degrades so much that they fall into the sun), so you just keep the asteroid train going round and round, pulling the Earth a little at a time. Again, it wouldn’t do for the immediate crisis presumed by the film, but it could work in the real-life long-term scenario.

So here is the conclusion of the series – we have migrated from the problems of getting into Earth orbit, to moving around between orbits, to the vastly bigger goal of moving the entire Earth in its own orbit around the sun. The common feature – you’d better do the calculations right in order to get where you want, and your intuition about how to go from A to B is not always right!