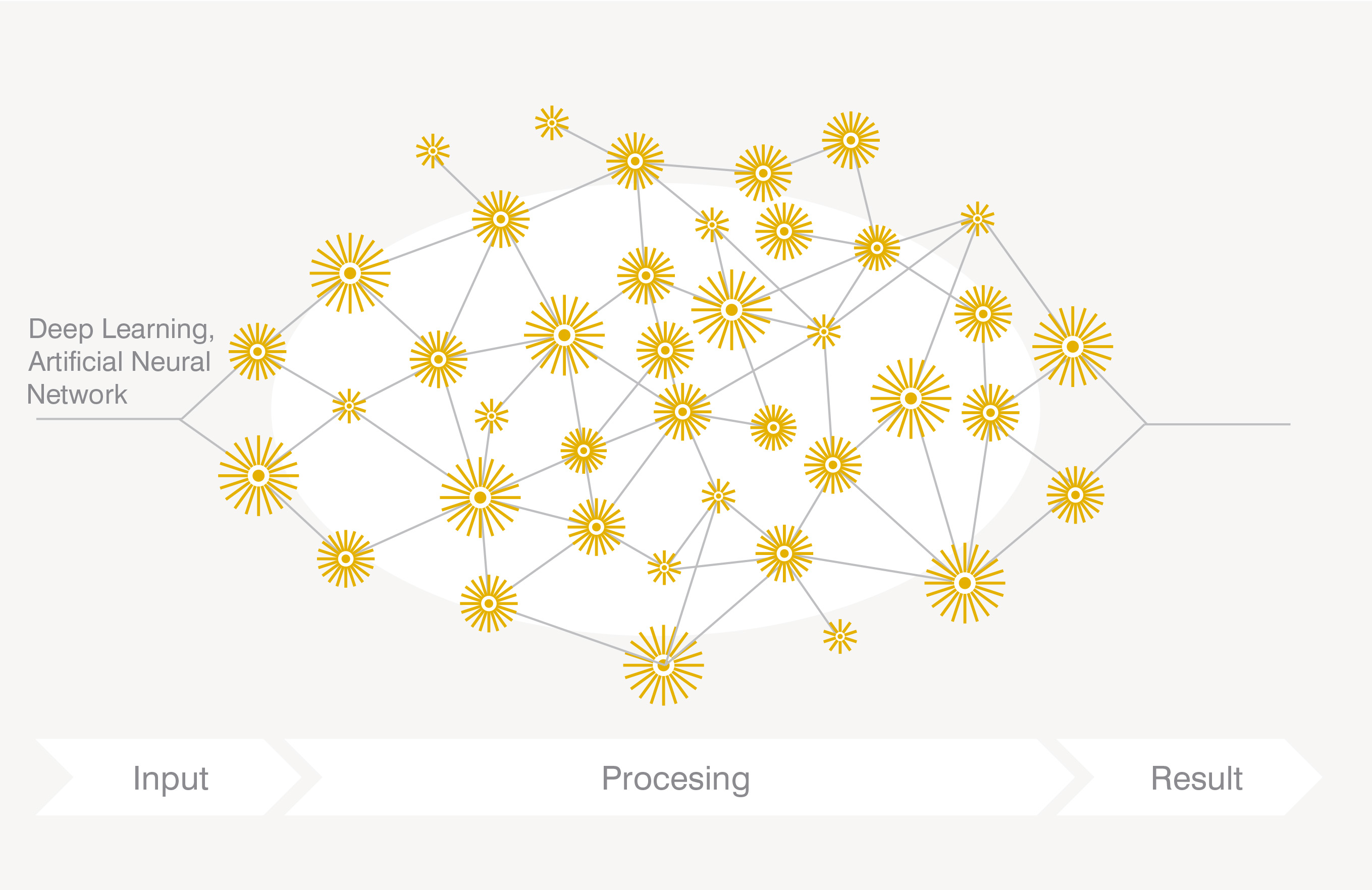

In my science fiction stories, I write about artificial intelligences called personas. They are not androids, nor robots in the sense that most people recognise – they have no specialised body hardware, are not able to move around by themselves, and don’t look like imitation humans. They are basically – in today’s terminology – computers, but with a level of artificial intelligence substantially beyond what we are used to. Our current crop of virtual assistants, such as Alexa, Cortana, Siri, Bixby, and so on, are a good analogy – it’s the software running on them that matters, not the particular hardware form. They have a certain amount of built-in capability, and can also have custom talents (like Alexa skills) added on to customise them in an individual way. “My” Alexa is broadly the same as “yours”, in that both tap into the same data store for understanding language, but differs in detail because of the particular combination of extra skills you and I have enabled (in my case, there’s also a lot of trial development code installed). So there is a level of individuality, albeit at a very basic level. They are a step towards personas, but are several generations away from them.

Now, one of the main features that distinguishes personas from today’s AI software is an ability to recognise and appropriately respond to emotion – to empathise. (There’s a whole different topic to do with feeling emotion, which I’ll get back to another day). Machine understanding of emotion (often called Sentiment Analysis) is a subject of intense research at the moment, with possible applications ranging from monitoring drivers to alert about emotional states that would compromise road safety, through to medical contexts to provide early warning regarding patients who are in discomfort or pain. Perhaps more disturbingly, it is coming into use during recruitment, and to assess employees’ mood – and in both cases this could be without the subject knowing or consenting to the study. But correctly recognising emotion is a hard problem… and not just for machine learning.

Humans also often have problems recognising emotional context. Some people – by nature or training – can get pretty good at it, most people are kind of average, and some people have enormous difficulty understanding and responding to emotions – their own, often, as well as those of other people. There are certain stereotypes we have of this -the cold scientist, the bullish sportsman, the loud bore who dominates a conversation – and we probably all know people whose facility to handle emotions is at best weak. The adjacent picture is taken from an excellent article questioning whether machines will ever be able to detect and respond to emotion – is this man, at the wheel of his car, experiencing road rage, or is he pumped that the sports team he supports has just scored? It’s almost impossible to tell from a still picture.

From a human perspective, we need context – the few seconds running up to that specific image in which we can listen to the person’s words, and observe their various bodily clues to do with posture and so on. If instead of a still picture, I gave you a five second video, I suspect you could give a fairly accurate guess what the person was experiencing. Machine learning is following the same route. One article concerning modern research reads in part, “Automatic emotion recognition is a challenging task… it’s natural to simultaneously utilize audio and visual information“. Basically, the inputs to their system consist of a digitised version of the speech being heard, and four different video feeds focusing on different parts of the person’s face. All five inputs are then combined, and tuned in proprietary ways to focus on details which are sensitive to emotional content. At present, this model is said to do well with “obvious” feelings such as anger or happiness, and struggles with more weakly signalled feelings such as surprise, disgust and so on. But then, much the same is true of many people…

A fascinating – and unresolved – problem is whether emotions, and especially the physical signs of emotions, are universal human constants, or alternatively can only be defined in a cultural and historical context. Back in the 1970s, psychological work had concluded that emotions were shared in common across the world, but since then this has been called into question. The range of subjects used for the study was – it has been argued – been far too narrow. And when we look into past or future, the questions become more difficult and less answerable. Can we ever know whether people in, say, the Late Bronze Age experienced the same range of emotions as us? And expressed them with the same bodily features and movements? We can see that they used words like love, anger, fear, and so on, but was their inward experience the same as ours today? Personally I lean towards the camp that emotions are indeed universal, but the counter-arguments are persuasive. And if human emotions are mutable over space and time, what does that say about machine recognition of emotions, or even machine experience of emotions?

One way of exploring these issues is via games, and as I was writing this I came across a very early version of such a game. It is called The Vault, and is being prepared by Queen Mary University, London. In its current form it is hard to get the full picture, but it clearly involves a series of scenes from past, present and future. Some of the descriptive blurb reads “The Vault game is a journey into history, an immersion into the experiences and emotions of those whose lives were very different from our own. There, we discover unfamiliar feelings, uncanny characters who are like us and yet unlike.” There is a demo trailer at the above link, which looks interesting but unfinished… I tried giving a direct link to Vimeo of this, but the token appears to expire after a while and the link fails. You can still get to the video via the link above.

Meanwhile, my personas will continue to respond to – and experience – emotions, while I wait for software developments to catch up with them! And, of course, continue to develop my own Alexa skills as a kind of remote ancestor to personas.