The second part of this quick review of the Future Decoded conference looks at things a little further ahead. This was also going to be the final part, but as there’s a lot of cool stuff to chat about, I’ve decided to add part 3…

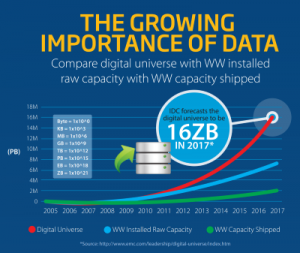

So here’s a problem that is a minor one at the moment, but with the potential to grow into a major one. In short, the world has a memory shortage! Already we are generating more bits and bytes that we would like to store, than we have capacity for. Right now it’s an inconvenience rather than a crisis, but year by year the gap between wish and actuality is growing. If growth in both these areas continues as at present, within a decade we will only be able to store about a third of what we want. A decade or so later that will drop to under one percent.

Think about it on the individual level. You take a short video clip while on holiday. It goes onto your phone. At some stage you back it up in Dropbox, or iCloud, or whatever your favourite provider is. Maybe you keep another copy on your local hard drive. Then you post it to Facebook and Google+. You send it to two different WhatsApp groups and email it to a friend. Maybe you’re really pleased with it and make a YouTube version. You now have ten copies of your 50Mb video… not to mention all the thumbnail images, cached and backup copies saved along the way by these various providers, which you’re almost certainly not aware of and have little control over. Your ten seconds of holiday fun has easily used 1Gb of the world’s supply of memory! For comparison, the entire Bible would fit in about 3 Mb in plain uncompressed text, and taking a wild guess, you would use well under that 1 Gb value to store every last word of the world’s sacred literature. And a lot of us are generating holiday videos these days! Then lots of cyclists wear helmet cameras these days, cars have dash cams… and so on. We are generating prodigious amounts of imagery.

So one solution is that collectively we get more fussy about cleaning things up. You find yourself deleting the phone version when you’ve transferred it to Dropbox. You decide that a lower resolution copy will do for WhatsApp. Your email provider tells you that attachments will be archived or disposed of according to some schedule. Your blog allows you to reference a YouTube video in a link, rather than uploading yet another copy. Some clever people somewhere work out a better compression algorithm. But… even all these workarounds together will still not be enough to make up for the shortfall, if the projections are right.

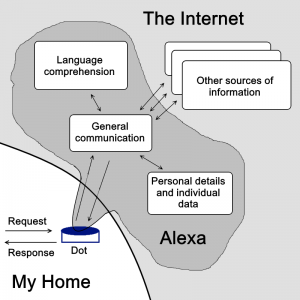

Holiday snaps aside, a great deal of this vast growth in memory usage is because of emerging trends in computing. Face and voice recognition, image analysis, and other AI techniques which are now becoming mainstream use a great deal of stored information to train the models ready for use. Regular blog readers will know that I am particularly keen on voice assistants like Alexa. My own Alexa programming doesn’t use much memory, as the skills are quite modest and tolerably well written. But each and every time I make an Alexa request, that call goes off somewhere into the cloud, to convert what I said (the “utterance”) into what I meant (the “intent”). Alexa is pretty good at getting it right, which means that there is a huge amount of voice training data sitting out there being used to build the interpretive models. Exactly the same is true for Siri, Cortana, Google Home, and anyone else’s equivalent. Microsoft call this training area a “data lake”. What’s more, there’s not just one of them, but several, at different global locations to reduce signal lag.

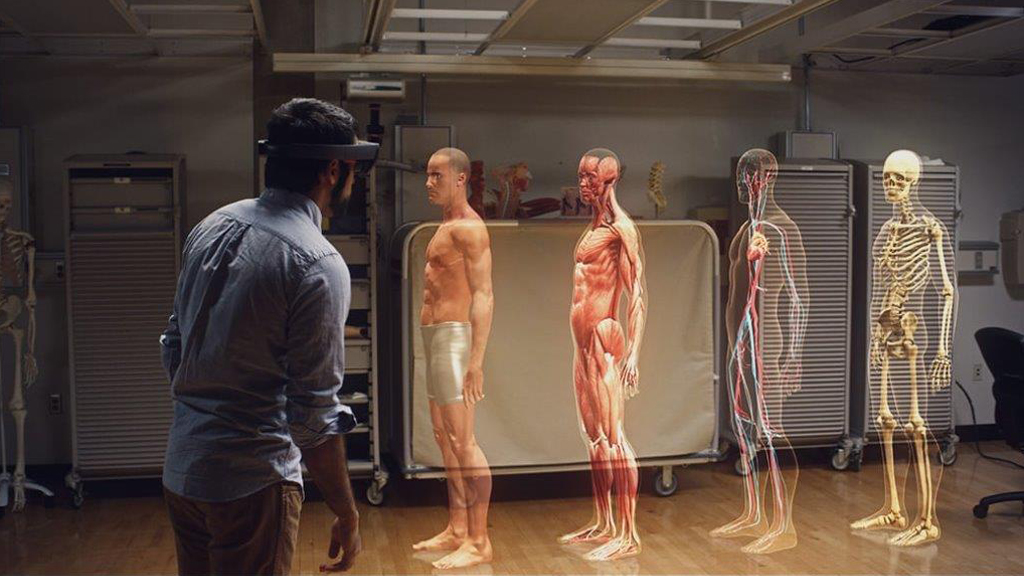

Hopefully that’s given some idea of the problem. Before looking at the idea for a solution that was presented the other day, let’s think what that means for fiction writing. My AI persona Slate happily flits off to the asteroid belt with her human investigative partner Mitnash in Far from the Spaceports. In Timing, they drop back to Mars, and in the forthcoming Authentication Key they will get out to Saturn, but for now let’s stick to the asteroids. That means they’re anywhere from 15 to 30 minutes away from Earth by signal. Now, Slate does from time to time request specific information from the main hub Khufu in Earth, but necessarily this can only be for some detail not locally available. Slate can’t send a request down to London every time Mit says something, just so she can understand it. Trying to chat with up to an hour lag between statements would be seriously frustrating. So she has to carry with her all of the necessary data and software models that she needs for voice comprehension, speech, and defence against hacking, not to mention analysis, reasoning, and the capacity to feel emotion. Presupposing she has the equivalent of a data lake, she has to carry it with her. And that is simply not feasible with today’s technology.

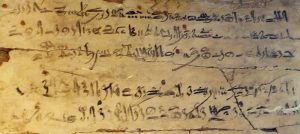

So the research described the other day is exploring the idea of using DNA as the storage medium, rather than a piece of specially constructed silicon. DNA is very efficient at encoding data – after all, a sperm and egg together have all the necessary information to build a person. The problems are how to translate your original data source into the various chemical building blocks along a DNA helix, and conversely how to read it out again at some future time. There’s a publicly available technical paper describing all this. We were shown a short video which had been encoded, stored, and decoded using just this method. But it is fearfully expensive right now, so don’t expect to see a DNA external drive on your computer anytime soon!

The benefits purely in terms of physical space are colossal. The largest British data centre covers the equivalent of about eight soccer grounds (or four cricket pitches), using today’s technology. The largest global one is getting on for ten times that size. With DNA encoding, that all shrinks down to about a matchbox. For storytelling purposes that’s fantastic – Slate really is off to the asteroids and beyond, along with her data lake in plenty of local storage, which now takes up less room and weight than a spare set of underwear for Mit. Current data centres also use about the same amount of power as a small town, (though because of judicious choice of technology they are much more ecologically efficient) but we’ll cross the power bridge another time.

However, I suspect that many of us might see ethical issues here. The presenter took great care to tell us that the DNA used was not from anything living, but had been manufactured from scratch for the purpose. No creatures had been harmed in the making of this video. But inevitably you wonder if all researchers would take this stance. Might a future scenario play out that some people are forced to sell – or perhaps donate – their bodies for storage? Putting what might seem a more positive spin on things, wouldn’t it seem convenient to have all your personal data stored, quite literally, on your person, and never entrusted to an external device at all? Right now we are a very long way from either of these possibilities, but it might be good to think about the moral dimensions ahead of time.

Either way, the starting problem – shortage of memory – is a real one, and collectively we need to find some kind of solution…

And for the curious, this is the video which was stored on and retrieved from DNA – regardless of storage method, it’s a fun and clever piece of filming (https://youtu.be/qybUFnY7Y8w)…