Last week I spoke about science fiction and fantasy, and the crossover world between them. Today I want to look at another genre which offers a twist on the normal world. Many of my author friends write historical fiction – stories based around real historical contexts or people.

My own series of Late Bronze books, which were my first real foray into writing books at all, fit neatly into that category. Kephrath, the town at the centre of those three books, is a real place, and the wider events fit in with one interpretation of the scanty historical record. The people I describe are credible for their place and time, but they are imaginary. Obviously I’d like Damariel, the village priest and seer, to have really lived in history, but we don’t know, and probably will never know for sure.

Now, by setting those books at the end of the Late Bronze Age – around 1200BC or so – I gave myself a huge advantage. This wasn’t my original motive: I simply liked that part of history and wanted to approach it in fiction. But the unexpected advantage is that our knowledge of that time is very scant.

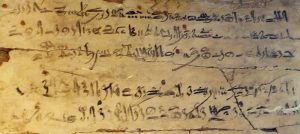

Serious academic debates take place over how to understand particular texts, or how to reconcile apparent contradictions. The regnal dates of Egyptian pharaohs are often speculative by years or even decades (despite the seemingly definitive values often written in books or web pages), and that uncertainty multiplies when you look to other nations. Accurate details of anybody lower in rank than the most elite are extremely sparse. So I am writing in a place where fixed facts are scattered very sparsely.

Now many of my friends do not have this luxury. They are writing in places and times where recorded facts hem them in on all sides. Their stories are still fiction, but their characters often have little freedom of action in their densely packed surroundings.

This wouldn’t matter so much – after all, a story is a story, you’d think. But a small number of reviewers are ruthless in their critique of perceived anachronisms, and waste no opportunity to highlight them. Now, don’t get me wrong, I enjoy research along with everyone else – but one feels that such reviewers miss the point that they are, in fact, reading fiction. I am sure that this is a tiny minority of the total readership, but they seem to exert undue influence, certainly over the sensibilities and anxieties of authors.

I have every respect for authors who, despite these difficulties, persevere in writing about places and times that they thoroughly love. And I’m certainly not suggesting that those who write other kinds of books are simply trying to avoid trouble: all of us in the indie world write what we do because that’s what we want to write about! But it is interesting that there are other close relatives of historical fiction which avoid some of the pitfalls.

There’s alternate history – at some point in the past, events diverged from what we know. A classic of this kind is Pavane, by Keith Roberts, where the timeline branches with the assassination of Queen Elizabeth I. But there are many others – probably the best known to many readers of this blog will be Alison Morton’s Roma Nova series. History unfolds a bit like our own… but also a bit different, and depending on the intention of the author either the similarities or the differences can be centre stage. So long as the world is internally consistent and convincing – which is no simple job – it doesn’t really matter if the facts get , let us say, jumbled up.

Another option is historical fantasy – a setting from history is chosen, but with a twist. The twist can be to take seriously beliefs and assumptions of a past age – such as the reality of magic, for example. Or it can be a much more radical departure. Guy Gavriel Kay, in The Lions of Al-Rassan, presented what was essentially the complex political and religious situation in Moorish Spain as Christianity started to recover territory. And yet… it also isn’t that. The world isn’t quite true to that portion of our own history, but has its own quirks and direction. (I read it with a book club, and it didn’t quite work for me as a novel, but I have every admiration for the feat of imagination involved.

Science fiction occasionally gets in on the act, as well. Ursula LeGuin used her considerable knowledge of sociology and anthropology to root her alien cultures in a credible past. So one of the cultures in Rocannon’s World is a bit like meeting Medieval Europeans… but again, it’s not quite like meeting them. And fantasy novels of course need a plausible culture to root themselves in, whether that be the familiar territory of elves and orcs, or something from elsewhere in the world.

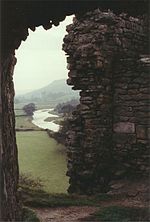

Meanwhile, of course, there are those brave souls who set their books in this world, in a real part of history, and with their characters surrounded by real historical individuals. For my part, if and when I return to history from the intoxicating world of science fiction, it will probably be back in the ancient past – much longer ago than the comparatively recent times of the Late Bronze Age. We shall see.