Here is the next in the series of character studies from The Flame Before Us, presented in the form of interviews.

Today’s interview is with Hekanefer, formerly a Mitsriy scribe attached to a military unit stationed in Gedjet and part of the army responsible for defending the province. He is now living in Shalem.

I find his house amongst a maze of similar ones, in a street close beside the city wall. He has just arrived there at the end of the day. His hands are spotted with inks of various colours, and after inviting me in he disappears briefly to wash his hands. I look round while waiting for him. The tools of his trade are arranged neatly on a table, topped by a bundle of pens and brushes tied with cord.

He comes back into the room with two beakers of beer and passes me one.

“My thanks for your hospitality.”

“The pleasure is mine, and you honour my house by your visit.”

We both drink. “Is the beer to your liking?”

“It is very good. Your own brew?”

“Surely not. I have no skill at that. My brother Ramose brought it from the Beloved Land recently. I have learned to enjoy the wine of this land, as I cannot usually get good beer. This is now only a rare treat.”

“Your parents sent it?”

“Oh no.” He laughs shortly. “Ramose acquired it somewhere in the sedge lands on his journey here. Neither of my parents has spoken to me since I decided to stay in this province, and broke off the marriage promise they had made for me when I was a youth. Look.”

He points to an irregular scrap of papyrus which he has attached to a wall. There is a very short line of writing near the top, too small to read at this distance.

“They were outraged at my decision. If I do not submit to their will and return by the end of the year, they will deny that I am their son.”

“And will you go?”

“No. Too much is happening here. I will not go back there.”

He stands up again and prowls around the room, full of energy.

“I have joined a group of craftsmen here in the city. Another Mitsriy man leads us. We support each other, train one another with new skills, commend our colleagues’ work to attract new patrons. It is good. It is what my people should be doing all across this land.”

He sits again, leaning in close to me to impress his meaning.

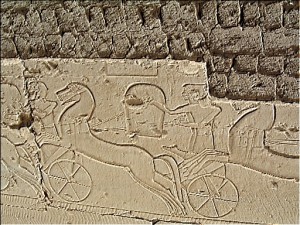

“Look now, take the field of war as example. I was with our soldiers, you know. Our chariots – the best men in our detail, chosen for their skill – were defeated by a gang of youths with javelins. It was the end of a way of life. Now, our great king took the lesson into his heart, and he ordered us to learn to fight in the new way. Do you follow?”

I nod, drawn in to the tale by his intensity.

“When we learned to fight like that, we started to find victory. But some of the men shrank back. They preferred to keep to the old ways and die, rather than reach for the new ways and live.”

He sits back, and his voice returns to its original measured tones.

“Well, my parents still cling to the old ways. They would have me hide away beside the River, marry a dull girl for some minor social advantage, and be head scribe for a local farmer, recording weights of crops and the punishment of slaves. I would have none of that.”

I knew a little of his background already.

“So you left your position as army scribe and settled here in Shalem.”

“I resigned on the day we heard of the battle along the coastal plain between my people and these newcomers. But it was not the battle that persuaded me: it was the treaty settlement which did that. We were abandoning the province, in all but name. My people should be out here, leading and inspiring the lands around, not shrinking back behind the Reeds and waiting to see what happens.”

“Are you happy here?” I gesture around the little house and its contents. “With your work? Your life?”

He gets up again and shows me a sheaf of partially finished items. There is a mixture of papyrus, wood, and clay, and a quick glance shows me that his writing spans several different formal styles.

“My work is appreciated. I am commissioned by the great ones of this city and the towns around – they call them daughter towns out here. My skills are in demand.”

“Tell me what you do?”

He pulls out one after another of the items as he replies.

“This is the written form of an oath granting title to land. This is a route itinerary going from Shalem to the holy mountain Tsaphon. Here, I am particularly proud of this one: it is the family record of one of the noble houses of the city, counting back eight generations and telling the tale of each. You will see that most of these items are written in the Kinahny signs. From time to time I still use the true writing, but not very often now.”

As he sips at his beer, I decide to chance the question.

“And your personal life? Now that you have broken off your family’s arrangement.”

He laughs.

“There is a man and wife who fled from Ikaret, who have a daughter. She is pleasant enough, but the parents make it very difficult for me to be familiar with her. And they insist on delaying matters beyond all reason. She and I have been very secretive, and I am fortunate that she was angry with her parents.”

He waves a hand dismissively.

“Some event or other on their journey here: I do not know the details. I treat the affair as a game; otherwise I would have abandoned the pursuit long since. In any case, this is a city, and I was with soldiers when I first arrived. There are other ways to find entertainment.”

He replaces the work in progress on its table and arranges the pots of ink in a neat row, colour by colour.

“This life is exhilarating. My heart is content with all that has happened. This time last year I lived in a narrow place, with the rest of my life planned out. All that has changed. I cannot imagine going back to the Beloved Land for many years yet.”

He pours us both another beaker of beer, and he tells me of his home, far away in another land. For all his bold words, the awareness of loss hovers always in the background.

Next time, the interview will be with Labayu, a Kinahny man from Kephrath who was living in the north of the land as the invaders approach.