Part of the background of all of my Kephrath books is Egypt. I call this the land of the Mitsriy – the name reflects both the biblical and modern Arabic names for that nation, whereas Egypt comes to us via a roundabout route through Greek.

Ancient Egypt was not as a rule interested in conquest per se, in the way that the later Assyrians, Babylonians, or Romans were. They were usually satisfied with securing a buffer area of tribes and cities to both north and south. These vassals rendered tribute of various kinds – goods, valuables, or people for the most part – in return for their local rulers being left in place by the Pharaoh. Loyalty was rewarded by support against enemies, rebellion (real or imagined) by punitive action.

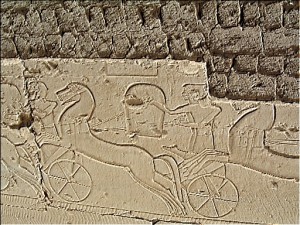

Egypt appointed regional governors – one was at Gaza (Gedjet in the stories) – but control was light. The area was not regularly policed: military action was normally a direct response to some provocation, though now and then flag-waving marches took place. Indeed, rivalry and internal fighting between cities seems to have been positively encouraged, perhaps to prevent wider alliances being formed. A few militaristic pharaohs certainly did campaign through Canaan northwards, even reaching the Euphrates River on occasion. But the purpose here was to establish zones of control with reference to the other Great Kings of the age – Mitanni and the Hittites for the most part – and there was no attempt to set up permanent garrisons in these areas.

This system started to break down around the end of the 19th dynasty (soon after 1200BC). Threats arose from other quarters, including north Africa and across the Mediterranean sea, and weaker pharaohs reduced the level of activity in the provinces. The major trade and defence route along the coast – The Sea Road – was defended all the more heavily, but elsewhere the Egyptian presence thinned out. The last great pharaoh in military terms of this era was Rameses III, who successfully defended Egypt against several attacks by The Sea Peoples and from Libya. Even he, however, decided that the only successful way to defend Canaan was to make terms with the invaders and grant them land. This event is recounted at the end of The Flame Before Us.

It used to be thought that Egyptians disappeared almost overnight from Canaan, at the end of the Bronze Age. This simple picture has been replaced by the understanding that Egyptian decline was a long and complex process. There was a continued – if reduced – presence in Canaan for a few hundred years. To be sure, there was no longer a serious military presence, and Egyptian words and wishes no longer commanded the same respect and obedience that used to be the case. But Egyptian cultural influence – building styles, pottery, systems of government, and habits of language and writing – persisted, and were influential in shaping the future of the kingdoms which emerged from this time, including the Israelites.

It’s always tempting with history to imagine “what-if” scenarios. What if the Egyptians under Rameses II had been more successful at the Battle of Qadesh against the Hittites, and gained control of the whole region up to Turkey? What if a more vigorous foreign policy had held the Sea Peoples back further north, avoiding the necessity to give territory away in the Gaza area? What if the Egyptians had poured more energy into linking up with the civilisations of Mesopotamia, instead of falling behind technologically and (in the end) being overrun? But these are for another day…