Exodus is set in a near-future earth in which today’s threat of global terrorism has pushed America into virtual dictatorship. Although still nominally democratic, personal freedom has been almost entirely sacrificed to military and economic interests. But this is simply the stage for the book’s real plot – securing an escape route to another solar system for a small group to avoid the consequences of a late-detected asteroid strike. Like so many stories these days, Exodus is part of a trilogy, and the story is left on the verge of the next stage.

Buy Exodus from Amazon.co.uk

Buy Exodus from Amazon.com

The plot is quite diverse, dealing with political machinations in the US as well as the selection process for the passengers, a glimpse of the scientific advances needed for the journey, and a little about the shipboard life on the way. A striking feature of Andreas’ writing is that she is not afraid to skip over spans of time where nothing much happens, in order to focus on the next key event. So for example very little is said of the actual journey through space.

The plot is quite diverse, dealing with political machinations in the US as well as the selection process for the passengers, a glimpse of the scientific advances needed for the journey, and a little about the shipboard life on the way. A striking feature of Andreas’ writing is that she is not afraid to skip over spans of time where nothing much happens, in order to focus on the next key event. So for example very little is said of the actual journey through space.

The characters are almost exclusively American, but of quite a limited range – Hispanic names are there, but I don’t recall any native American, Indian or far-east Asian names. Perhaps this was supposed to mirror the generally paranoid thinking of the society, but it felt rather unreal to me. As regards the rest of the world, Europe is largely there to provide scientific know-how for the project and then wave the ship goodbye, and no other countries get a look-in at all. One scientific goal of the journey was to secure genetic diversity on the new world, and I suspect that in this regard, one would have to class the mission a failure. But again, perhaps this is really saying that political agenda always trumps scientific ideals.

I felt there were some odd omissions. Interpersonal relationships are almost entirely platonic – in a bunch of about 1600 people who think they are the last representatives of humanity, about the closest we get to romance is one man musing to himself that one of the women “didn’t look too bad”. More seriously, having had a careful explanation before launch of the compelling need for exponential population growth from the start, nothing is then done about this. I feel sure that, especially in a centrally dominated society but for sound survival reasons as well, some fraction of the women would have been pregnant before landing. But so far as the plot of the book is concerned, only politics, seen as the pursuit of authority and dominance, is important.

Technically the Kindle version has been reasonably well produced. There were a number of typos, only a few of which interrupted reading. The prose style is very plain, and coming from a historical fiction background I prefer something richer. The main obstacle was the paragraph length which through most of the book was huge, often spanning multiple Kindle page turns I would strongly recommend that another edit trims this down into digestible chunks which fit better with an ereader page.

I thought a lot about a final rating and felt in the end that the interest value of the plot just about pushed this from three to four stars. I was never at serious risk of giving up and I did want to see the travellers through to their destination. But I would have liked Exodus much more if the issues mentioned had been tackled, and I did feel that parts of the story didn’t quite hang together as they should.

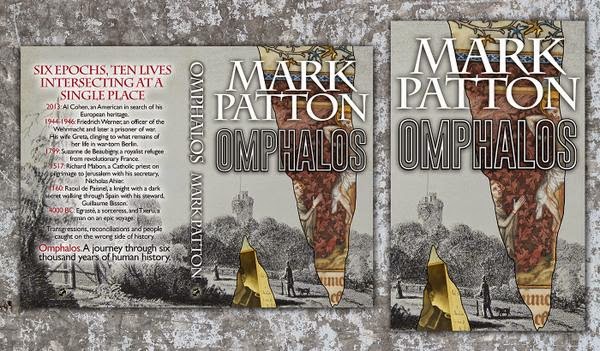

The closest analogy I have read is The Source, by James Michener, but Mark achieves here something which in my view is more memorable and more human. The Source tended, despite the author’s efforts, to lose the personal dimension against the grand sweeps and calamities of history. Also it progressed linearly forwards through history rather than giving the sense of diving deep, and then slowly surfacing again. Mark, while still setting his various characters in times of flux and crisis, never allows these settings to obscure personal dramas and interpersonal relationships. Sometimes the links between the layers are obvious; other times there are only little clues in the narrative to spark the connection.

The closest analogy I have read is The Source, by James Michener, but Mark achieves here something which in my view is more memorable and more human. The Source tended, despite the author’s efforts, to lose the personal dimension against the grand sweeps and calamities of history. Also it progressed linearly forwards through history rather than giving the sense of diving deep, and then slowly surfacing again. Mark, while still setting his various characters in times of flux and crisis, never allows these settings to obscure personal dramas and interpersonal relationships. Sometimes the links between the layers are obvious; other times there are only little clues in the narrative to spark the connection. I guess what has remained the biggest disappointment for me in Ursula LeGuin’s words is the sense of establishmentarianism in them. She persevered at writing kinds of literature which were, in the early days, not reckoned to be “proper” genres at all. Now they are accepted, and she herself has been accepted – which is fantastic. But does that then mean that the establishment becomes the norm? Perhaps all it has done is tried to absorb what was – and hopefully still is – a voice of dissent.

I guess what has remained the biggest disappointment for me in Ursula LeGuin’s words is the sense of establishmentarianism in them. She persevered at writing kinds of literature which were, in the early days, not reckoned to be “proper” genres at all. Now they are accepted, and she herself has been accepted – which is fantastic. But does that then mean that the establishment becomes the norm? Perhaps all it has done is tried to absorb what was – and hopefully still is – a voice of dissent. The raw textual material in the Hebrew Bible bearing on Jerusalem is as follows. Judges chapter 1 has two references. In verse 8 we read

The raw textual material in the Hebrew Bible bearing on Jerusalem is as follows. Judges chapter 1 has two references. In verse 8 we read The Summer Queen follows the life of Eleanor of Aquitaine (Alienor here, a more accurate representation of the name) up to the point where she is about to arrive in England as the new queen of this land. She is already a highly travelled and shrewd ruler of her own territory and others, and the expectation is set in the reader that things are on the up, after some unpleasant experiences in the first part of her life.

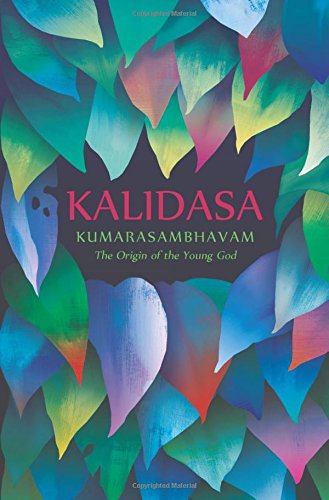

The Summer Queen follows the life of Eleanor of Aquitaine (Alienor here, a more accurate representation of the name) up to the point where she is about to arrive in England as the new queen of this land. She is already a highly travelled and shrewd ruler of her own territory and others, and the expectation is set in the reader that things are on the up, after some unpleasant experiences in the first part of her life. The theme of the work is the courtship of Shiva and Parvati, as imagined through their personal interactions, the participation of other individuals, and the rich echoes of their emerging love in the natural world. The 8th section celebrates their sexual union after their wedding. In due course this will lead to the birth of the Young God of the title, who will liberate parts of the natural and divine world from oppression. Over the years, this final section has been sometimes been regarded as an improper subject for poetry, and has often been omitted from published versions. To me this immediately brought to mind the Song of Songs in the Hebrew Bible, which has from time to time only gained acceptance by being read as allegory rather than literal delight.

The theme of the work is the courtship of Shiva and Parvati, as imagined through their personal interactions, the participation of other individuals, and the rich echoes of their emerging love in the natural world. The 8th section celebrates their sexual union after their wedding. In due course this will lead to the birth of the Young God of the title, who will liberate parts of the natural and divine world from oppression. Over the years, this final section has been sometimes been regarded as an improper subject for poetry, and has often been omitted from published versions. To me this immediately brought to mind the Song of Songs in the Hebrew Bible, which has from time to time only gained acceptance by being read as allegory rather than literal delight. This extract first appeared

This extract first appeared  The Wessex Turncoat follows apprentice blacksmith Aaron Mews, from his home near Fordingbridge, Hampshire, through forced entry into George III’s army, over to Canada. The second half of the book describes his part in the disastrous 1777 campaign against the rebellious American colonies.

The Wessex Turncoat follows apprentice blacksmith Aaron Mews, from his home near Fordingbridge, Hampshire, through forced entry into George III’s army, over to Canada. The second half of the book describes his part in the disastrous 1777 campaign against the rebellious American colonies. Do Not Forget Me Quite spans nearly twenty years of a family’s life, starting on the eve of WWI. The main focus is on the father, John, who feels morally obliged to enlist in the medical corps as hostilities commence. His wife Emma resents this, and in part the book explores the ensuing personal and family distress that follows for the couple and their children. The most evocative section is when John is invalided home before the end of the war, and John and Emma are forced to confront the consequences of their choices. Towards the end of the book Emma fades out, and their eldest daughter replaces her as a female protagonist.

Do Not Forget Me Quite spans nearly twenty years of a family’s life, starting on the eve of WWI. The main focus is on the father, John, who feels morally obliged to enlist in the medical corps as hostilities commence. His wife Emma resents this, and in part the book explores the ensuing personal and family distress that follows for the couple and their children. The most evocative section is when John is invalided home before the end of the war, and John and Emma are forced to confront the consequences of their choices. Towards the end of the book Emma fades out, and their eldest daughter replaces her as a female protagonist.