Today’s basic element is communication, and thousands of years of human development has shown that this indeed is a crucial feature in building society.

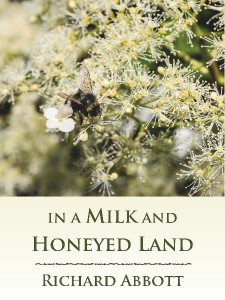

Before that, though, a quick mention of some author readings for Far from the Spaceports – whether you like YouTube, Daily Motion or Vimeo, you’ll be able to find them.

So, communication. It’s fair to say that as a species we have been quite obsessive in extending the scope and accuracy of our attempts to communicate. What began as an immediate interpersonal exchange has grown in range, variety, and diversity over the years. Nowadays, many people find themselves disoriented and frustrated when they cannot, virtually instantaneously, access the information they want.

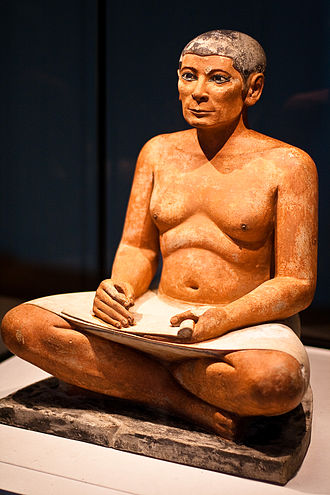

Wind back to the Late Bronze Age, and things were very different. The majority of people stayed within a short distance of their birthplace, and had direct contact only with the towns and villages in the neighbourhood. There were exceptions, and we do know that some people were well-travelled. Messengers, envoys, scribes, and traders would all be acquainted with a much wider scale of vision.

An army commander or religious leader might be called upon to travel to, or describe, remote locations, and the accuracy with which they could do this might make a world of difference to the outcome. We have topographical records and route lists from the ancient world, itemising the important features of a strange land, and how to navigate from the familiar into the unknown. And “travellers’ tales”, with vivid and usually speculative descriptions of other lands, have been a favourite story-teller’s ploy throughout history. I sometimes wonder if this accounts for today’s popularity of science fiction and fantasy – with so few unknown places left on the planet we know, we are easily persuaded to look into other realms.

There was, essentially, no way to send a message to some distant place other than making a physical journey, either in person or by proxy. On a battlefield, some orders might be signalled by horns or other instruments, or by flags and banners, but the intent had to be simple and easily understood. Right through until the modern era, the dust and confusion of battlefields has led to endless confusion and lost opportunities. On the political scale, the various empires of the ancient world struggled to keep a balance between the expansionist mindset of rulers, and the sheer practical difficulty of keeping hold of territories once acquired. The Persian empire – which would be swept away by Alexander the Great – had a complex and largely effective system of messengers and roads, but an independently-minded ruler of a remote city-state would still enjoy a very large degree of freedom.

It is hard for us to comprehend just how vast the world has seemed throughout history, if you think in terms of sending a message. Less than a century ago, some of my family members were posted to Singapore for a time. The rest of the family treated the event as though it was a permanent goodbye. True, there was surface mail, but it was extremely slow, and erratic at best. So it was safest to assume that this could be a one-way journey. Fast forward to 2015, and I was able to use my mobile phone to call my parents in England, from a hotel room near Delhi, India, to make sure that they had made a safe transition from place to another. The worst problem I faced was that the connection was a bit crackly.

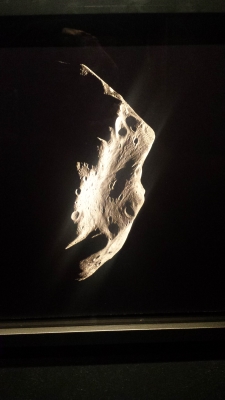

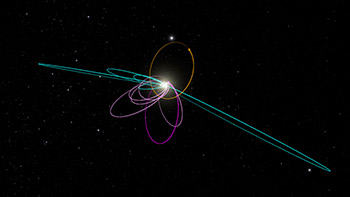

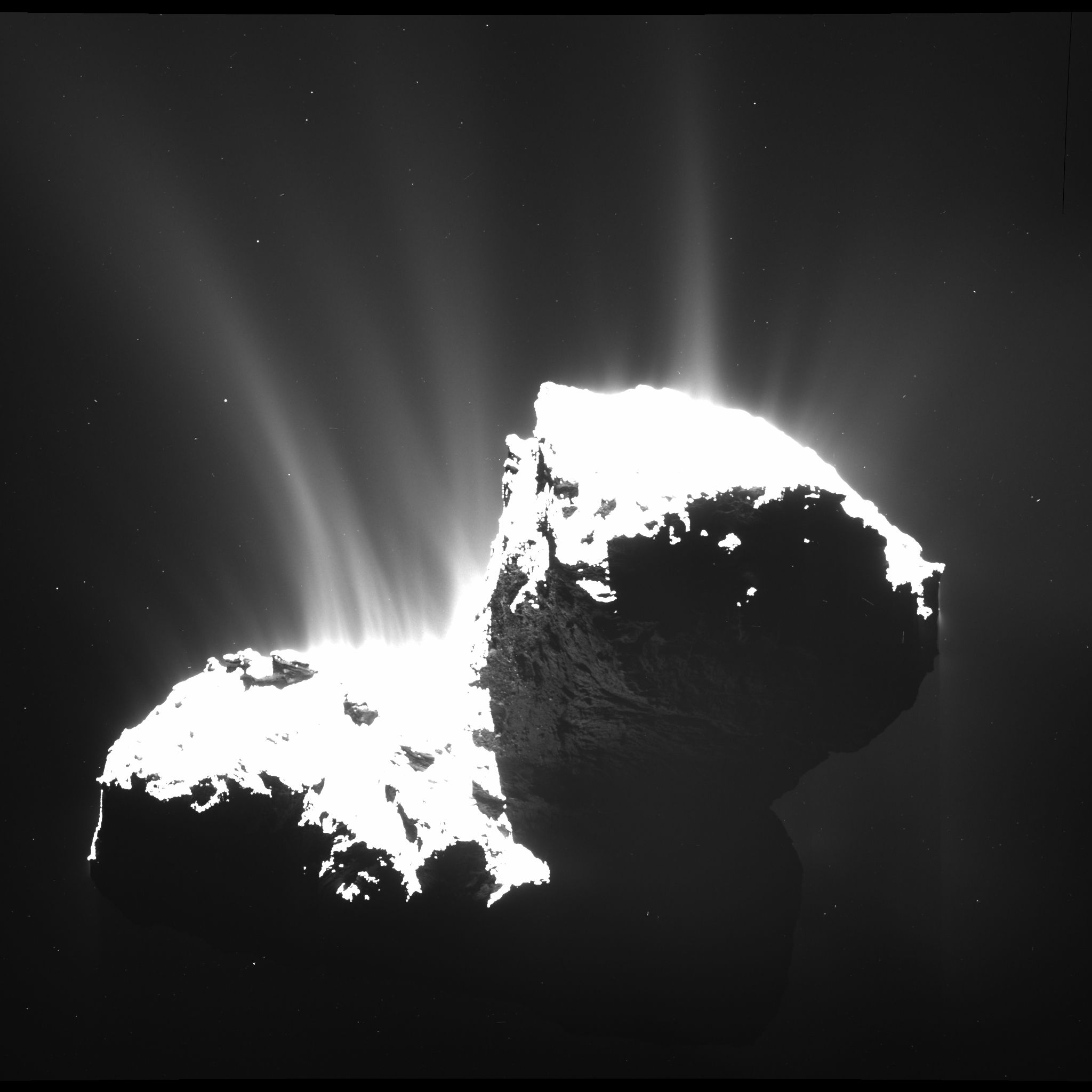

Moving on again, into the time of Far from the Spaceports, we have again lost the possibility of talking real-time to people. Even when the Apollo spacecraft were going to our moon, we had to learn to get used to about a second and a half lag in the signal. As we go further out, the lag gets longer, as signals travel at the speed of light back from the craft. When the New Horizons probe was passing Pluto and sending images back, the signal lag was about 4 1/2 hours. The corresponding time for Voyager, much further out again, is about 18 hours. Even the relatively modest distances that Mitnash and Slate have travelled out to the asteroid belt mean that they have somewhere between 1/4 and 1/2 hour delay each way, depending on the relative positions in their orbits. It can take an hour for Mit to get an answer to a simple query.

How will we readjust to a lifestyle where almost instant communication is no longer possible? It’s a strange middling position between our present day, when we can chat in real time without hindrance to a person anywhere in the world, and where we were before radio, when carrying a message to another country could take weeks or months. It is clearly a limitation that science fiction film makers find frustrating.

The universe of Star Trek, while acknowledging that physically going from place to place takes time, tends to show instantaneous real-time chat between the ships concerned and the headquarters back on Earth. For Trek geeks, there is a lot of online chatter about how this might happen, most of which seems to me to simply push the problem around without solving it. The basic idea that moving objects takes time, but moving information happens without delay, seems to go back (at least in fiction) to Ursula LeGuin’s Rocannon’s World, when Rocannon sends an instantaneous message back to Earth with the coordinates of the enemy base: “They can send death at once, but life is slower…” (it’s a fine book, and well worth reading for lots of reasons).

Mitnash and Slate, however, work within the constraints of what we know. I have not assumed that some extraordinary scientific breakthrough will change all this just yet (though I aware of, and intrigued by, current ideas for using quantum mechanical entangling to send instantaneous signals). So their world is one that has to manage with chat lag – and this affects their personal relationships as well as the simple acquisition of information. What kind of friendship and intimacy is possible when every communication is frustrated by long gaps? People – and I suppose artificial intelligences – can handle enforced separation for long periods of time and remain loyal to each other. But what about situations where you can almost have a conversation, but not quite?