I have seen several blog articles recently on the subject of fictional dialogue. However, I have not yet seen any which have tackled the specific issue of dialogue in historical fiction. Most are concerned with matters such as use of slang or idiomatic language in contemporary writing – whether this works or not, how quickly it ceases to be relevant, and how to use it.

Historical fiction faces slightly different problems, though, and I want to tackle these over a few blog articles, especially as they are closely related to the translation of historical texts. For one thing, many of us who write about the past are also writing about people speaking another language – even the English of Chaucer’s time is quite different in certain ways from modern English. Along with a lot of other people, I write about a place and time where the characters’ language was scarcely related at all to English.

Historical fiction faces slightly different problems, though, and I want to tackle these over a few blog articles, especially as they are closely related to the translation of historical texts. For one thing, many of us who write about the past are also writing about people speaking another language – even the English of Chaucer’s time is quite different in certain ways from modern English. Along with a lot of other people, I write about a place and time where the characters’ language was scarcely related at all to English.

A reviewer of In a Milk and Honeyed Land commented that she felt that some of the dialogue was too modern, and in particular picked out my frequent use of “look” or “see“. We had a great discussion about this – one of those really positive online experiences. My basic answer was that in the Hebrew Bible, this is actually one of the more common words (hinneh). In older translations this is typically represented by “lo” or “behold“, and most modern translations simply omit it… ironically, given the discussion, because they consider it too archaic! Egyptian has a similar word (mek) which is also frequently used, and similar comments can be made of other languages of the region,

The basic idea is that this word pulls the reader or listener into the action alongside the protagonist. For example, in Genesis 15, Abram is protesting to God: “And Abram said, “Look, to me you have given no seed: and look, one born in my house is my heir.” (Both words “look” are variations of hinneh).

So from my point of view, my characters’ use of “look” or “see” is quite period-correct… but evidently it did not carry this idea to the reader in question, who herself writes historical fiction set in another age, so is very well informed.

This set me thinking about how to present historical dialogue. I suspect that for many people, “ho varlet, why dost dare stand before me? Unhand me and get onst thy knees!” would seem genuinely historical. But to my Late Bronze characters, such phrasing (always presuming that anybody actually spoke like that, which I suspect is unlikely) would be unthinkably far in the future.

This brings me to translation. By and large there are two schools of thought about this. One is to take the text and translate very literally, keeping as close as possible to the original words and sentence structure. This is usually associated with academic or other “serious” contexts. At another pole is an approach called “dynamic equivalence“, in which the translator basically tries to write what, in their opinion, the original author would have said if they were speaking today.

You can make a case for both of these, and just now I am not going to promote one way above the other. Pretty obviously, dynamic equivalence makes a text more accessible to a casual audience, but at the cost of deliberately discarding forms and patterns present in the original. In another blog post I’ll give some examples of this.

For today it’s enough just to open up this problem. How do you make your characters speak in ways that as author you are confident has roots in your period of choice… while at the same time persuading readers they are reading something set in the past?

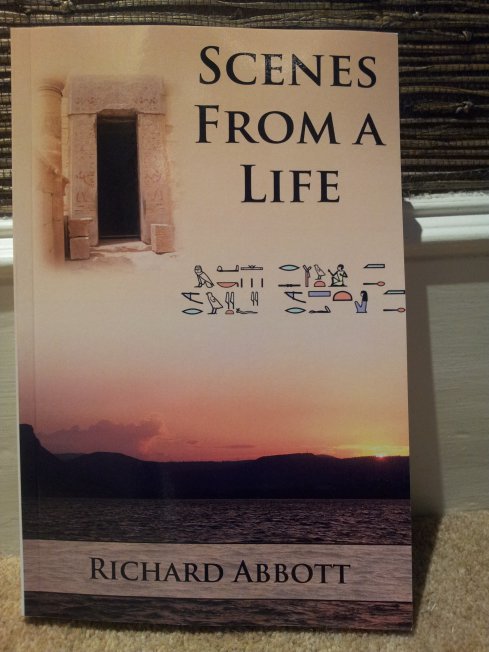

I have read books which adopt the dynamic equivalence approach and simply use modern phrasing, on the grounds that this is how the people would speak if they were alive today. As a reader, this does not work for me, but I can see the logic. And clearly it is not suitable to write totally in the characters’ idiom – how many people would enjoy In a Milk and Honeyed Land or Scenes from a Life if the dialogue was in Canaanite, early Hebrew, or Egyptian? How far should one go in trying to capture something of their way of speech, and the occasional struggles of trying to communicate cross-culturally?

And how far, I wonder, does the problem extend to other genres? When might writers of fantasy or science fiction use archaic-sounding language to good effect? Quite apart from the general techno-babble style of things, I remember being fascinated by Isaac Asimov’s coining of the word “richified” (to mean “bribed“, of course) to signal a slightly backward world… though still with space flight and other things which are futuristic to us!

Time for a review amongst all the excitement of

Time for a review amongst all the excitement of

The typical pattern is to open with a state of stability and peace, which is then disrupted in some way – perhaps by a natural crisis, or by wickedly motivated individuals. The disruption may be presented from several different points of view, depending on the length of the work. The pivotal event is at the centre to resolve the crisis – in some texts it might be a battle, for example, but in others it will be a celebration of a god, nation or individual. Merenptah’s Israel Stele has “A great wonder has occurred for Egypt“. The Hebrew “Song of the Sea” (Exodus 15, first half) has “Who like you among the gods? Yahweh!“. After the central affirmation the situation ‘unwinds’, commonly in symmetric ways to the opening layers, and the setting is restored to peace and stability.

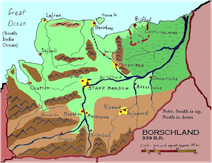

The typical pattern is to open with a state of stability and peace, which is then disrupted in some way – perhaps by a natural crisis, or by wickedly motivated individuals. The disruption may be presented from several different points of view, depending on the length of the work. The pivotal event is at the centre to resolve the crisis – in some texts it might be a battle, for example, but in others it will be a celebration of a god, nation or individual. Merenptah’s Israel Stele has “A great wonder has occurred for Egypt“. The Hebrew “Song of the Sea” (Exodus 15, first half) has “Who like you among the gods? Yahweh!“. After the central affirmation the situation ‘unwinds’, commonly in symmetric ways to the opening layers, and the setting is restored to peace and stability.  The background is the same – the country of Borschland is part of a continent in the southern hemisphere of our world. This continent is sometimes in phase with us (and so accessible) and sometimes out of phase (and so in splendid isolation). The stories revolve around the occasional crossover characters who go from here to there and choose to remain. For complex reasons, the whole continent is gripped with a passionate enthusiasm for ice skating in general and ice hockey in particular. You don’t need to have read the first novel to enjoy this book, since they form a loosely connected series rather than parts of a trilogy or some such.

The background is the same – the country of Borschland is part of a continent in the southern hemisphere of our world. This continent is sometimes in phase with us (and so accessible) and sometimes out of phase (and so in splendid isolation). The stories revolve around the occasional crossover characters who go from here to there and choose to remain. For complex reasons, the whole continent is gripped with a passionate enthusiasm for ice skating in general and ice hockey in particular. You don’t need to have read the first novel to enjoy this book, since they form a loosely connected series rather than parts of a trilogy or some such.