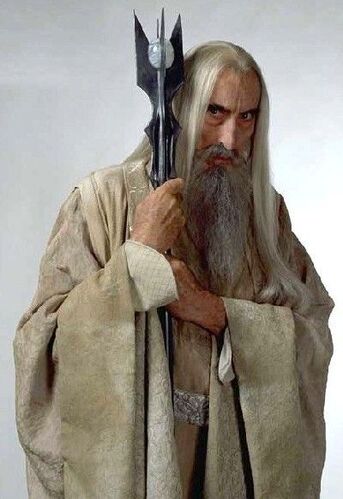

Before I start on compost, here’s a remarkable picture of Mars taken with a fairly ordinary camera, from a spaceship about the size of an average briefcase. Called a CubeSat, two of these were launched alongside the Mars Insight probe, and whistled past Mars while said probe made its way to a safe landing. More about Mars later…

It’s the time of year when – at least in the northern hemisphere – you put compost on your garden as part of bedding it down for the winter. These days that’s generally easy – you trot along to your local garden centre and get 3 bags for £12, or whatever the deal is, and you spend a suitable amount of time distributing it around your little patch. Someone else has done most of the hard work of transforming original plant and animal matter into an easy-to-use commodity.

But in a big garden you can do things a bit differently (and if you’re a farmer, you’ll be up into another league altogether, which I am not going to presume to write about). You can gather up said plant and animal matter yourself, stow it away somewhere dark and warm, add whatever extra bits and pieces you want, wait the better part of a year… and there you have your own compost. Which is what has been happening up here in Grasmere – last year’s rotted stuff, including pig manure, was ready for distribution. Not only that, but all those leaves which have been building up in the garden got put into the compost bins, waiting for their turn next year!

Now, this process has been going on pretty much ever since people discovered how to cultivate crops. Last year’s plant waste, together with stuff from whatever animals you had, and most likely human waste as well, got stashed away and spread on the fields when ready. The process has got steadily more scientific over the years, with additives to ensure that the ratios of chemicals are appropriate for the crops in question, but fundamentally nothing has changed.

But now think about what happens when you go out into space. You can grow some crops hydroponically, but this needs water which has been prepared with suitable levels of nutrients… which needs those nutrients to be available. We’ve done it up on the ISS, where the astronauts have prepared bits and pieces of salad to accompany their regular rations. But most of what is eaten in orbit has had to be carried there in a cargo supply ship. Suppose we add a couple of large modules on to the ISS and start growing things on a bigger scale. Then maybe we just need to ship the nutrients up there. That helps.

Now go a bit further. You have built a moonbase, or are living in a dome on Mars, and you want to grow your own stuff. In one sense you are surrounded by soil, but it is totally lifeless soil. It probably has a number of the basic chemicals you need, but none of the complex organic substances that your plants need. So you’re back to shipped-in nutrients… until you have either built up some human waste (and allowed it to decompose in some suitable way), or waited a year for the spare bits and pieces from one year’s harvest to rot down into compost.

This is probably reminding you of The Martian – Mark Watney manages to grow potatoes using the left-behind waste of his fellow crew-members. It goes pretty well until an accident exposes all his carefully prepared plants and compost to sub-zero temperatures and an air pressure less than that on Everest… which kills the lot and causes him to revert to Plan B (or probably, Plan F by that stage in the book). All necessary stuff, and emphasising the point that to grow Earth plants, you have to have built up a stock of Earth compost to encourage their growth.

So as I was piling leaves into the compost houses to being their long process of rotting down for this time next year, I suddenly wondered about our future. Out of all the unlikely cargos to be shipped out to our future colonies out on the Moon, Mars, the asteroids, and wherever else, wouldn’t it be supremely funny if most of them were shipping out the raw ingredients to make compost? Not an eventuality that makes its way into fiction very much… but how else are you going to grow your food?