I have been wanting for some time to do occasional posts on the subject of religion in the second millennium BCE. Today’s post is a general start, loosely based on the rather short piece I did for the Orangeberry blog tour (Orangeberry book tour main page, or more specifically a guest post at Just My Opinion)

In that among other things I wrote

I enjoy writing about religion, or more exactly, I enjoy writing about people who have a religious faith. It is simply not possible to write about most ages of past human experience without including the religious life somewhere. Too often in books you come across a few very simple, and in my view quite unrealistic stereotypes. So there is the rabid fundamentalist, who reacts with violence to anything that seems to threaten his or her world view. Or there is the ruthless cynic, who knows it’s all make-believe and just wants to exploit others. Or there is the naïve villager, who is duped and never questions the wider system. Or there is the wise sage who holds to personal spirituality without the inconvenient trappings of any specific religion.

Now, I have at various times in my life mixed with and known people of faith who belong to various different religions, and I have to say that these simple pictures do not do justice to most of them. In terms of religious faith as well as other areas of life, people are more complex, and more interesting, than these stereotypes. They have doubt as well as faith, selfish as well as noble motives, mixed feelings about the religious institution they belong to, and, usually, commitment to a specific form of religion rather than a vague abstraction. They are often keenly interested in other forms of religion as well as their own, even if they think that those are ultimately incorrect.

For today I want to think about the many facets of religious life. The one which seems most obvious, judging from some of the books I read, is that of doctrine. I suppose it seems easy to quantify and approach, and is frequently used as s soft target by hostile writers: “these simple deluded folk really believe that the world was made from a discarded banana skin” or some such. For writers of a scientific disposition, it may seem a natural way to define a religion.

But many people who are spiritually inclined are well aware that this is a very small part of the religious life. In actual fact, doctrine is a serious intellectual pursuit and is frequently, in part, hard to follow. It also typically, in recognition that both the universe and the human organism are fantastically complicated things, has ideas and concepts which at first sight appear completely contradictory. The Egyptians, along with other peoples, were fond of this, making the quest for “Egyptian theology” quite a fruitless one. Some religious traditions have deliberately used these oppositional ideas to try to jog people out of complacency.

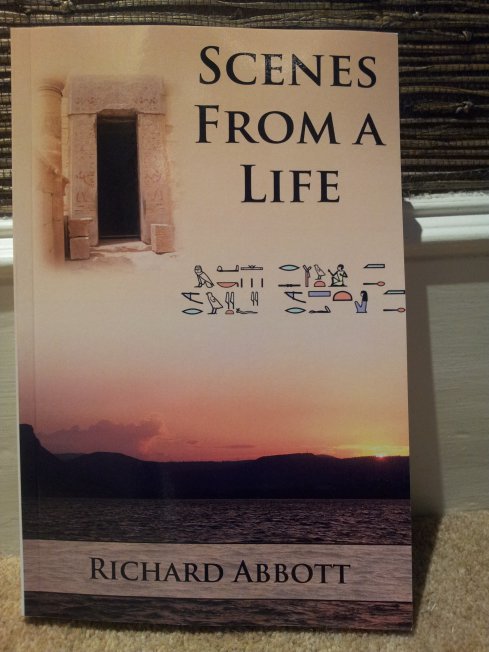

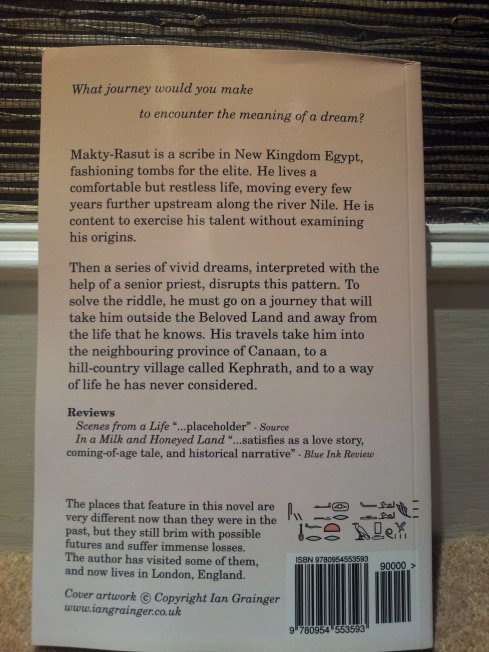

But more to the point, doctrine is not the centrally important thing to most religious groups that some writers present it as. To be sure, some groups place a very high store on sound knowledge, but still only as one facet amongst a much larger whole. In the Late Bronze Age world that I write about, doctrine is almost invisible. Readers will get very little sense of the details of Canaanite or Egyptian thinking from my books. The “favourite” goddess in Kephrath is Taliy, hardly one of the better known members of the Canaanite pantheon. Makty-Rasut, the main character in Scenes from a Life, expresses personal devotion to Seshat – again a figure that I suspect most people will need to use Google to learn about!

The second main area that you often find explored in fiction is spiritual experience; this typically gets a positive press, as it seems not specifically to tie in with the details of religion – “Trust your feelings, Luke”. It is certainly true that people recount their personal encounters with the numinous in very similar ways, regardless of their specific personal tradition. It is also true that these experiences are, seemingly, accessible to all, and evidence suggests that many, perhaps most people experience something of this at least once during their lives. Such experiences may be triggered by prayer or praise, but also by natural beauty, or sex, or moments of altruism. But equally, people who experience these moments more than just once in a lifetime have usually been involved with a particular religious tradition for a long time, and are thoroughly steeped in its particular disciplines and habits of thought. Even Luke has to disappear for an unspecified period of time to become trained and effective.

But there are other dimensions of religion which are often overlooked by writers. One is that of personal devotion. It seems attractive to some people to write about big temple ceremonies and lavishly dressed priests or priestesses – but in an agricultural world with no mass transportation, such pilgrimages must have been extraordinarily rare. Social classes below the elite may never have experienced them. For most people, the religious dimension of their life would be expressed in the home, or the village, with their families, friends, or next-door neighbours. Archaeological evidence and ancient texts support each other here, and we have strong evidence of household-level observance of rites and duties. I have equipped Kephrath with a high place, a small stone circle within and around which both religious and social events happen. We know that most settlements in the ancient near east had such arrangements of stones, though we do not know the details of how they were used. Today’s “community centres”, so important to isolated immigrant groups at risk of losing their identity after moving to a new nation, serve a similar purpose of blending religious observance and social need. In the absence of a dedicated religious building, the community centre serves as the focal point. Makty-Rasut, in Scenes from a Life, has a small statue of Seshat that he carries with him as a personal focus for prayer and devotion wherever he is living.

And this brings me on to the final dimension of the religious life for today – the social aspects. For many people in today’s world, in many different religions, social dimensions are in fact the most important ones that define their identity. Many Jews, Christians, Moslems, Hindus, Buddhists, and so on find their main experience of religion in the intricate web of the society around them. Huge numbers of people now and in the past have identified their religion not by rational assent to a doctrine, nor by vivid personal experience, but by the intimacy of their social network, and the place they and their family hold within it. The shape of a society (or a sub-group within society) is fashioned as an expression of religious commitment. Professor Dunbar has written of the cohesive effect of religion within human society (see for example a presentation he gave at a debate on race, religion and inheritance) – and also questioned whether this can or should continue in the future. That is a subject for another post – for today it is enough to recognise the central place of social interactions within people’s religious life. One of the central difficulties Makty has to face, though he does not really know how to articulate this, is how to step outside his familiar social circle into a different world. His statue of Seshat serves as a link back to the world he has known.

Enough for today – in a while I shall be writing about how religion changed between the second millennium Bronze Age and the first millennium Iron Age.