I’ve been reading quite a lot recently about prehistoric sites in the British Isles in particular two short books by Aubrey Burley covering stone circles and henges (Prehistoric Astronomy and Ritual, and Prehistoric Henges)

A definition from an archaeology text book is:

“Henge: a type of ritual monument found only in the British Isles consisting of a circular area, anything from 150 to 1700 feet across, delimited by a ditch with the bank normally outside it”.

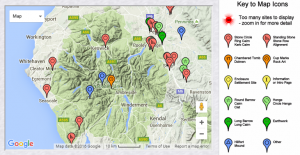

So I thought I’d add to my blog of a few weeks ago with some others through the rest of this summer. The research into these monuments is quite fascinating, especially the leaps and bounds in understanding their orientation which have been achieved in the last few decades. To cut a long story short, the main choices are between alignment with some nearby feature on the land, or some far away feature in the heavens.

Local ground features include prominent hills or mountains, especially where their shape is unusual or striking. Several Scottish sites are oriented towards hills which look like breasts, and it is not hard to imagine a belief that these were visible signs of an Earth goddess. So when you’re looking at a site, the first thing to do is look out beyond it to the skyline.

Astronomical alignments include both sun and moon, typically at key calendar points such as midsummer, midwinter, or the equinoxes. Plus the cardinal compass points. The evidence suggests that earlier sites were often aligned with respect to the moon, and were subsequently adapted by a later generation to a solar orientation. More of this another day, but the point here is that we often need to think twice about sites. It is easy from to imagine that the site was put together as a single coherent whole. The historical reality may be of a series of changes over many years, with new settlers reusing and repurposing older places. Stonehenge is a particularly good example of this.

Our own appreciation of lunar alignments has grown dramatically in recent years. Even as a casual tourist, it is quite easy to work out where the sun will rise at the calendar festivals using nothing more complicated than a compass. It remains predictably the same every year, so even without a compass it does not take long to mark out the cycle.

However, the moon’s movement is considerably more complicated, varying over a cycle lasting about 18.6 years. This is primarily because of the complex relationship between the earth’s orbit round the sun, and the moon’s orbit round the earth. Also, because the solar 365 day cycle contains almost exactly 13 lunar 28 day months, the quarterly solar festivals cannot all mesh neatly with the same moon phase. It takes a long time of regular watching to spot the patterns, and be able to understand and predict where the moon will rise and set.

The key observations over this 18.6 year cycle are of the most extreme northerly and southerly limits of rising and setting, called the Major and Minor Lunar Standstill points. These vary from place to place, partly because of changing latitude and partly through the accidents of the terrain. At latitude 55°, not far north of the cluster of henges near Penrith, the rising point of the full moon varies in its cycle by 12.5° either side of the place where the sun rises – a big shift along the landscape as seen from the centre of a henge! Even if the basic pattern is known, each region must carry out its own observations of where the moon will rise and set at these stationary points. This is where the local and distant alignment issues interact with each other. If you have recognised the exact direction to look in, what more natural impulse is there than to place your circle where that direction lines up with a prominent hill or valley?

It’s worth mentioning here that although henges may be restricted to the British Isles, lunar alignments are not. All over the world people have found places where the 18.6 year cycle is shown off to good advantage.

The astronomy of the moon’s movements is now well understood, and over the last few decades has been applied to stone circles and henges. It is not an easy task, given the considerable damage done to sites over the years by natural wear and tear together with human acts such as ploughing over ditches and banks, or robbing stones for building work. But aerial photography has provided huge insights into layout no longer visible on the surface, and some careful archaeology has uncovered items placed in particular locations.

Astonishingly, given the difficulties of observation and long baseline required, our remote ancestors have showed themselves to be well aware of the intricacies of the moon’s movement, and able to codify it in their monuments. Often these key directions are pinpointed by buried items. While there may well have been some visible signal such as a banner, it seems that the real importance was a sacred one. Apparently it was important to signal to the invisible world that you knew these patterns. In the absence of written texts from this era, we can only speculate.

To close this blog post with a striking but only very loosely related picture, here is the first image of Jupiter and a few of its moons, sent back by NASA’S Juno probe…