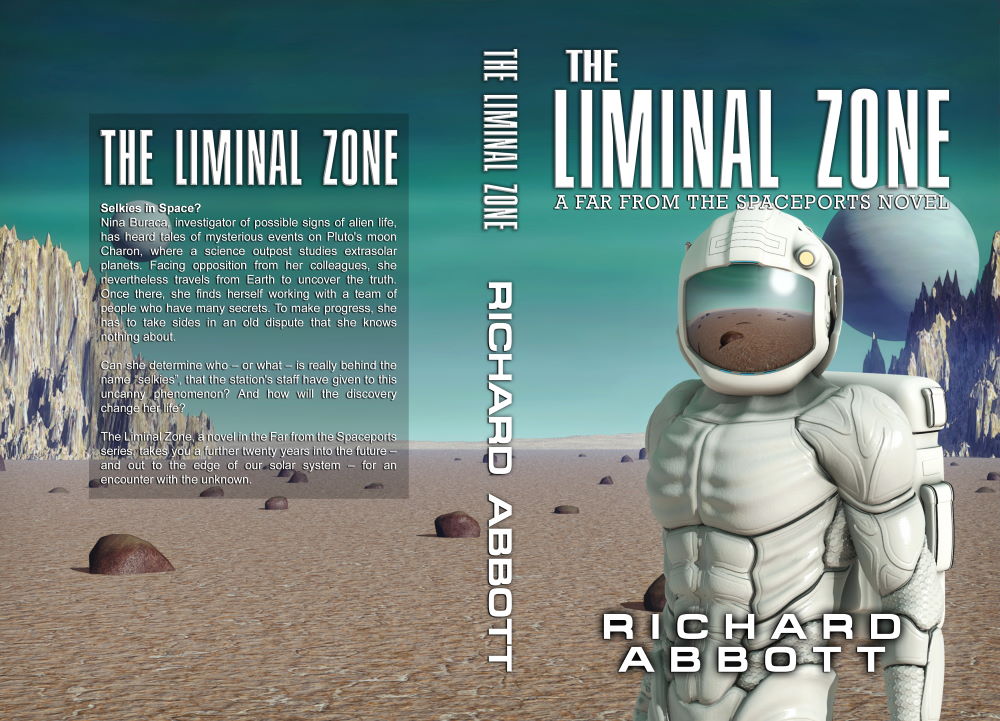

In something of a departure, I used IngramSpark (IS) as my print-on-demand supplier for The Liminal Zone, rather than Amazon’s CreateSpace (CS), which I used for my previous novels. This was largely at the suggestion of my local bookshop, who indicated that they would, and do, order from IS, but wouldn’t order from CS. Presumably the connection with Amazon as a commercial threat is too close for comfort. Now, I’d read occasional comments from other authors that they had had problems with IS, in particular with refusal to accept pdf files on submission. As things turned out, I had no problems with the internal part (the manuscript itself) and only one problem, easily resolved, with the cover.

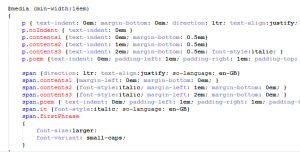

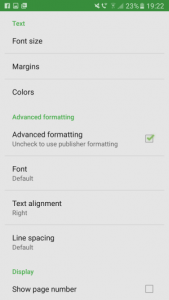

Now, readers of this blog will probably know that I am committedly geeky when it comes to generating manuscripts, and prefer to use a format method which is as close as possible to the one used by whatever software tool processes the manuscript. So for Kindle editions, I use HTML files, since that is what the Amazon tool kindlegen really prefers. Yes, it will accept other formats, and munch through them, but sometimes throws out formatting artefacts which are hard to resolve. By staying with HTML and similar files, I stay in control of the process. A typical kindlegen project looks like this:

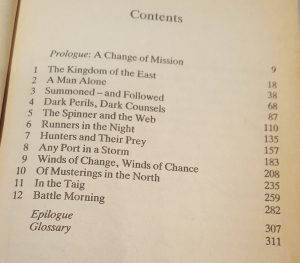

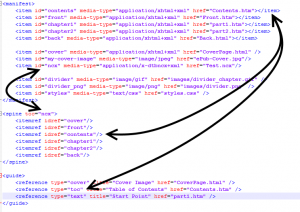

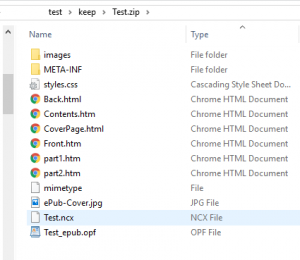

- opf file – the overall controller file providing metadata like ISBN, keywords, description, etc, and identifying other components

- multiple HTML files for the front and back matter, a contents page, and individual chapters

- a stylesheet determining how things look

- a cover image, in jpg or png format

- other interior images, in any of several formats

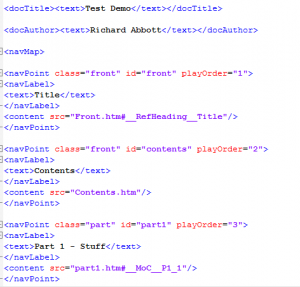

- an ncx file, which is equivalent to a table of contents but feeds in to the kindle hardware navigation, rather than being presented to the user inside the book

If you are so motivated, you can gather different elements in their own sub-folders inside the main project folder, just so long as the opf file points to the correct location.

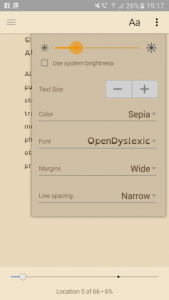

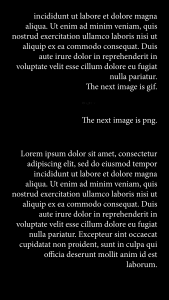

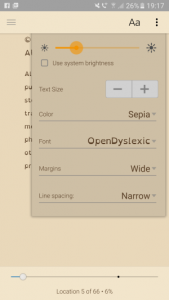

This structure has lots of advantages – first, it appeals to the programmer in me, who likes things to be laid out in a systematic and atomic manner, consistently between projects. Secondly, I can at any time generate a kindle version and deploy it to a real device, so I can catch layout weirdness early on, and also test out different viewing options that a reader might prefer. That’s hard to do if you just write in Word or a similar package. Finally, I can put placeholder content in at roughly the right location – for example my cover image for ages was nothing like the splendid one I ended up with, but was a rather boring image of the right dimensions. Likewise, I could work on sections at any point in the book, carry out edits, or simply tidy up the front and back matter if I felt lacking in inspiration.

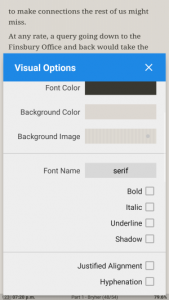

What about the paperback? IS, just like CS and presumably every other print-on-demand supplier, wants to get from you a properly formatted pdf file which adheres to specific industry standards. And here is where some folk run into problems. It is entirely possible to generate pdf files from pretty much any program you choose – Word, Notepad, and so on – simply by selecting the print-to-pdf option in your menu. However, it turns out that individual software teams are not always as careful as they might be about the compliance of their print-to-pdf commands. Sure, you get something which will display in a web page, or whatever, but when given to something more particular about standards – like the IS submission process – things do not always come out right.

So I don’t use Word – instead I use an online tool which turns out pdf files which adhere to the relevant standards. The one I use is now called Overleaf (formerly ShareLatex) and was originally designed to help university staff and students to get their papers, dissertations, and whatever, correctly laid out. It is based on a text layout engine called latex, which contains all kinds of support for mathematical equations and the like – which I don’t need – but in particular allows settings for page size, running headers and footers, correct location of new chapters, font and style support, and such like. Even better, it is based on a project layout which is directly parallel to my Kindle layout above. The files have a .tex extension rather than .htm or .html, and there is no equivalent to the ncx file, but in other respects it all maps across.

Which is great – when I get to the stage of wanting a paperback version, I reproduce my Kindle project layout in a new Overleaf project, then copy across the text from my source files into the corresponding tex file, compile the whole, and voila… one standards-compliant pdf file. Now, that then generates a whole lot of additional work to check that characters are not spilling too far into the margins, and that widow and orphan lines are taken care of. Those edits have to be back-copied into the Kindle version. But it’s all very neat and orderly, and not only leaves me with a sense that all is properly organised, but also that the results are gong to be accepted first time. Which they were!

I mentioned that there was one small issue with the cover – this was a technical one relating to the use of what pdf standards designers call colour profiles. Basically these are a neat way to reduce file size by appealing to a commonly agreed list of colour mappings. It’s a great idea, but IS require cover files which don’t use them. Workaround – resave the file without the profile information, and accept the larger file size.

All in all, my experience with IS has been uniformly positive, and I would certainly choose them again.