A couple of weeks ago I went to a day event put on by Amazon showcasing their web technologies. My own main interests were – naturally – in the areas of AI and voice, but there was plenty there if instead you were into security, or databases, or the so-called “internet of things”.

Readers of this blog will know of my enthusiasm for Alexa, and perhaps will also know about the range of Alexa skills I have been developing (if you’re interested, go to the UK or the US sites). So I thought I’d go a little bit more into both Alexa and the two building blocks which support Alexa – Lex for language comprehension, and Polly for text-to-speech generation.

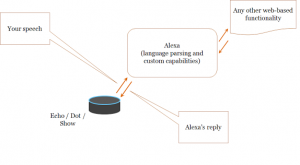

Alexa does not in any substantial sense live inside your Amazon Echo or Dot – that simply provides the equivalent of your ears and mouth. Insofar as the phrase is appropriate, Alexa lives in the cloud, interacting with you by means of specific convenient devices. Indeed, Amazon are already moving the focus away from particular pieces of hardware, towards being able to access the technology from a very wide range of devices including web pages, phones, cars, your Kindle, and so on. When you interact with Alexa, the flow of information looks a bit like this (ignoring extra bits and pieces to do with security and such like).

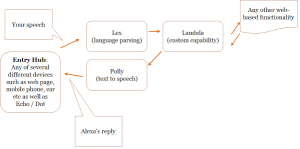

And if you tease that apart a little bit then this is roughly how Lex and Polly fit in.

So for today I want to look a bit more at the two “gateway” parts of the jigsaw – Lex and Polly. Lex is there to sort out what it is you want to happen – your intent – given what it is you said. Of course, given the newness of the system, every so often Lex gets it wrong. What entertains me is not so much those occasions when you get misunderstood, but the extremity of some people’s reaction to this. Human listeners make mistakes just like software ones do, but in some circles each and every failure case of Lex is paraded as showing that the technology is inherently flawed. In reality, it is simply under development. It will improve, but I don’t expect that it will ever get to 100% perfection, any more than people will.

Anyway, let’s suppose that Lex has correctly interpreted your intent. Then all kinds of things may happen behind the scenes, from simple list lookups through to complex analysis and decision-making. The details of that are up to the particular skill, and I’m not going to talk about that.

Instead, let’s see what happens on the way back to the user. The skill as a whole has decided on some spoken response. At the current state of the art, that response is almost certainly defined by the coder as a block of text, though one can imagine that in the future, a more intelligent and autonomous Alexa might decide for herself how to frame a reply. But however generated, that body of text has to be transformed into a stream of spoken words – and that is Polly’s job.

A standard Echo or Dot is set up to produce just one voice. There is a certain amount of configurability – pitch can be raised or lowered, the speed of speech altered, or the pronunciation of unusual words defined. But basically Alexa has a single voice when you use one of the dedicated gadgets to access her. But Polly has a lot more – currently 48 voices (18 male and 30 female), in 23 languages. Moreover, you can require that the speaker language and the written language differ, and so mimic a French person speaking English. Which is great if what you want to do is read out a section of a book, using different voices for the dialogue.

That’s just what I have been doing over the last couple of days, using Timing (Far from the Spaceports Book 2) as a test-bed. The results aren’t quite ready for this week, but hopefully by next week you can enjoy some snippets. Of course, I rapidly found that even 48 voices are not enough to do what you want. There is a shortage of some languages – in particular Middle Eastern and Asian voices are largely absent – but more will be added in time. One of the great things about Polly (speaking as a coder) is that switching between different voices is very easy, and adding in customised pronunciation is a breeze using a phonetic alphabet. Which is just as well. Polly does pretty well on “normal” words, but celestial bodies such as Phobos and Ceres are not, it seems, considered part of a normal vocabulary! Even the name Mitnash needed some coaxing to get it sounding how I wanted.

The world of Far from the Spaceports and Timing (and the in preparation Authentication Key) is one where the production of high quality and emotionally sensitive speech by artificial intelligences (personas in the books) taken for granted. At present we are a very long way from that – Alexa is a very remote ancestor of Slate, if you like – but it’s nice to see the start of something emerging around us.