I heard today that I had passed the study element of a Personal Alcohol Licence, which (after I have gone through a police background check and a few other formalities) allows me to authorise the sale of alcohol in England and Wales. Not in Scotland, Northern Ireland, or indeed anywhere else in the world, but I guess you have to start somewhere.

Now, this is far from my most advanced academic qualification, but the intriguing thing about this one is that it legally entitles me to supervise – and therefore take legal responsibility for – the public sale of what is undoubtedly a kind of drug. Without the licence, I can work under someone else’s supervision, but cannot just set up and flog booze on my own account. With it, and subject to a bunch of other constraints, I can do just that.

You can imagine that a fair proportion of the material, and the final test, focused around UK law relating to drink. There are obvious things to do with the age of the drinker, but I also learned that it is a specific legal offence to sell alcohol to someone who (in the considered opinion of the seller) is already drunk. Too much like shooting fish in a barrel, I suppose. Most of the laws fit around common sense, though as with any body of legal material you are left a little perplexed as to why specific conditions were imposed.

Anyway, all this set me thinking about law and qualification. The government of the day, however it was decided, has for a very long time indeed decided that it is entitled to a certain proportion of the profits from various kind of sales – and alcohol has typically been way up the list. And of course where rulers try to enforce a ruler, some subjects will concoct cunning schemes to get around the additional expense – excise duty spawns groups of smugglers almost by definition. But you only risk smuggling goods where the financial equation makes sense – small, easily concealed items where the tax duty is high enough that you can pocket a decent cut for yourself, while still leaving the buyer feeling they have done very well out of the deal.

So customs duties, and the body of regulations which underpin them, have been around for millennia. And – typically – part of those regulations consists of ways to appoint specific individuals as those few who are allowed to make transactions. In days of old, one suspects that many of these appointments were based on nepotism or bribery… if you had the right connections, or could stump up enough starting cash, you could find yourself in a comfortable position and set up for life. Nowadays the process is rather more transparent, and the barriers to entry are very much lower.

But equally, things have been tightened up in other ways. A couple of hundred years ago, it was fairly common for ex servicemen to use their prize money, or sign-off pay, or whatever they had saved up, to buy a little inn somewhere, and make a tidy living brewing or distilling booze of widely varying quality, and plying locals with the results. (Any pub you find called the Marquis of Granby recalls charitable donations by this 18th century gentleman who donated money to wounded servicemen). Provided you could afford a small building and a few bits and pieces to do the fermentation, you could set yourself up, no questions asked. These days, you have to go through hoops like planning permission, health and safety, police, plus of course getting a premises licence. There are all kinds of reasons why an apparently sound business plan might be rejected by officialdom.

So that is looking back… but what about forwards? Right now the only human outpost we have away from the Earth is the ISS. It’s not very far away – about 400km above the surface of the Earth, less than the distance from one end of England to the other. And I don’t suppose that the occupants have much privacy or opportunity to set up fermentation or a distillery up there. Though I did hear today that Budweiser has funded one of the science experiments on board, seeking to improve strains of barley with increased resistance to environmental stress. So maybe next year someone wil fund a experiment to make beer up there and see how yeasts behave in microgravity!

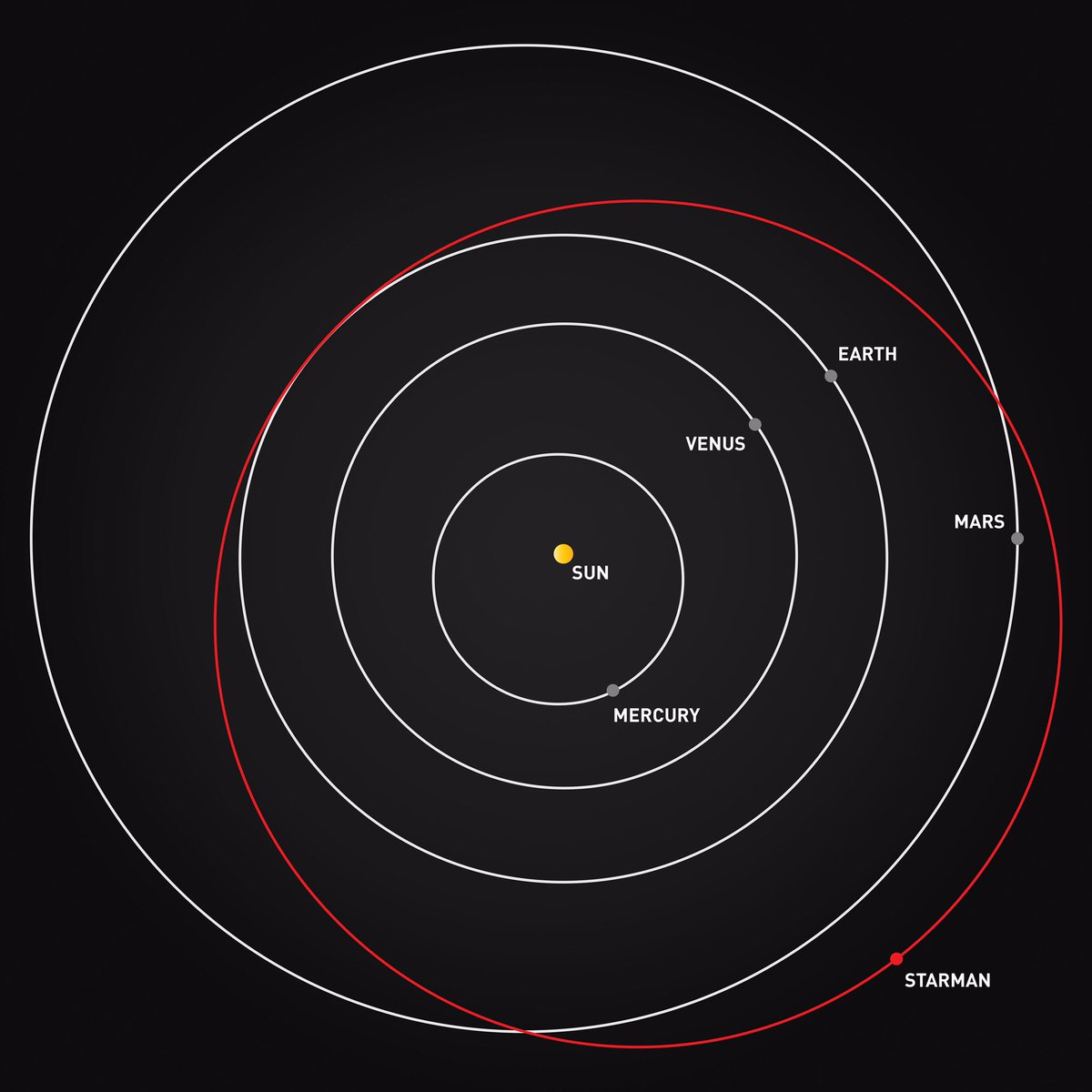

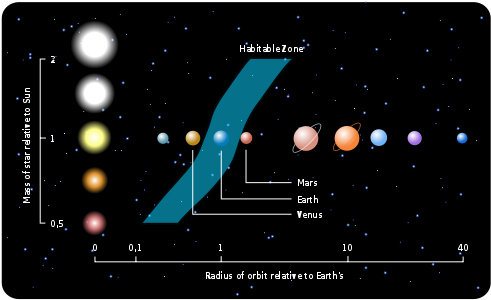

But let’s assume that within the next couple of decades we have an outpost or two somewhere else – the Moon, say, or Mars, or even a privately operated space station. How likely is it that nobody will attempt to ferment fruit or vegetable juices? And whose laws will be applied to regulate such an operation? Now run the scenario on a few more years, into the solar system I imagine for Far from the Spaceports and its sequels. There are a decent number of scattered habitats, each separated from the others by at least days, often weeks, and sometimes months of travel time. It will, I suspect, become impossible to try to enforce some kind of uniform system of laws.

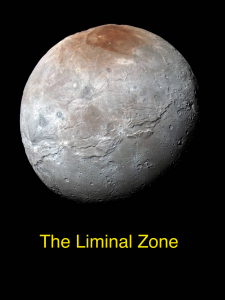

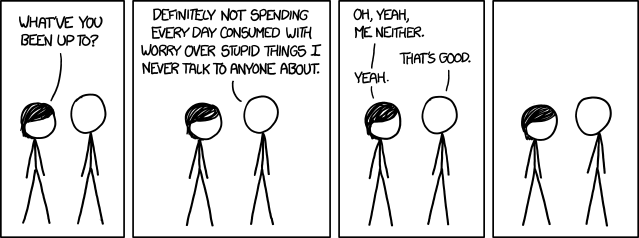

My guess is that each habitat will have its own local set of laws and customs – no doubt broadly consistent with each other, but differing in detail. Sure, you can send a message anywhere in the solar system within a day at most, but if you get a tip-off that the habitat on Charon is bootlegging some kind of moonshine drink that is not allowed on the Moon, it’s going to take your police three or four months to trek out there and investigate. Will they bother? In that kind of situation, I don’t think it is feasible to try to maintain a single unified system of laws and regulations. So now suppose I have trained for my personal alcohol licence here on Earth (which in fact I did), and then decide on a whim to travel out to Charon. Will a publican out there recognise my licence? Or will he or she make me study for a duplicate one, ending up with a signature of someone on Charon rather than Earth? Right now, in the present day, it is extraordinarily hard to transfer qualifications between countries in professions like teaching, nursing, psychotherapy, and so on – will things be any different when we’re scattered across a few dozen habitats? I suspect not, especially as my own new licence doesn’t even allow me to do stuff in Scotland!

All of which is why I like writing about that near-future band of time, when there is no Federation, no Galactic Empire, or whatever – only local enforcement of issues according to moral and social principles which makes sense to the occupants. I suspect the chief coordinating factor would be economic – if you felt that some particular habitat was doing things the wrong way, you wouldn’t trade with them. They would become isolated, and there’s nowhere in the solar system away from Earth that can actually be self-sufficient. Hence I write about economic and financial crime, as these are the things that seriously threaten lives and livelihoods.