I have just started reading a non-fiction book entitled The Inklings and King Arthur: J. R. R. Tolkien, Charles Williams, C. S. Lewis, and Owen Barfield on the Matter of Britain. It’s not a catchy title, but so far I am hugely enjoying the content. As you might expect, it’s academic in tone, consisting of a series of essays by different people all around how the various members of “The Inklings” approached and reworked Arthurian material. And inevitably it has provoked my own thinking in various ways.

The four men mentioned in the book title had very different views on life, religion and indeed most matters, but they were united on a few quite specific areas. One was that modern life as they witnessed it emerging was poor as regards its mythological underpinnings. Another was that the Arthurian legends – the Matter of Britain – were worth keeping alive, and retelling in ways relevant to their society.

Now, one of the fascinating things about Arthurian tales is that they are in constant conflict with one another. There is no original text, no authoritative canon of tales against which some particular version can be compared. Each subsequent reteller selects the pieces they want and rejects other pieces. They put the same characters into new settings, or mix up participants in a venture. The collection of stories is hugely diverse and contradictory. What’s more, as you push back in time to look for some point of origin, the picture becomes more confusing, not less. Some of the early traditions come from England, but others from Wales, France, and Scotland, and in many cases the direction of derivation can no longer be decide with confidence.

Authors drawing on the Arthurian tradition over the years since then have carried this habit on. Arthur and his knights have been cast into all kinds of different settings – futuristic, fantastic, or resolutely historical. Tolkein, Lewis and the other Inklings did the same – they borrowed bits and pieces as they saw fit, renamed individuals and recombined them in different settings, and energised the ongoing collection of tales with their own contributions.

Now this recombination of elements of older pieces of writing into newer ones is often called intertextuality. Usually it is a conscious choice on the part of an author, but sometimes it is unconscious, and simply reflects deep familiarity with the sources. That’s from the author’s perspective. Looked at from the reader’s point of view, it means that associations and emotions triggered by the older works are drawn forward into the newer ones.

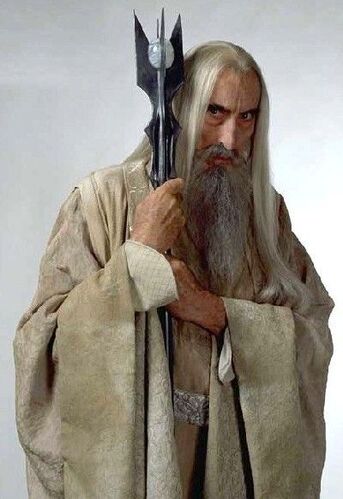

A similar process happens in film. If you have seen an actor play in a particularly striking role in one film, it is all but impossible not to see that previous character in the new one. Film-makers are, of course, well aware of this, and it often drives casting decisions. So when Christopher Lee appears as Saruman in the film version of Lord of the Rings, his previous roles in horror films constantly cast shadows around him.

Back with books and the Arthurian tradition, it has been argued that this ability to be reshaped into so many different forms is exactly what has kept it alive for so long, and through so many social changes. A fixed story that allows only one telling will wither and die, as the circumstances that gave birth to it fade into the past. By analogy with biology, successful stories are those which can adapt to new environments and new pressures.

All of which makes the quest for a historical Arthur, however interesting from a historian’s viewpoint, a rather pointless exercise from the literary one. Of course there are fascinating stories of Arthur and his companions to be told from a historical perspective – say a fifth or sixth century military leader after the Romans have left and before the Saxons consume the land. I have read some of those stories, and enjoyed them. But there are other stories of Arthur which are rooted in fantasy and magic, or where the quest for the Grail takes the questers out of our ordinary world. And stories where the company is located in another place and time. Or science fiction versions where the physical connection with England is at best tenuous. And the magic of intertextuality means that none of these are more or less proper than a conventional historical fiction version.