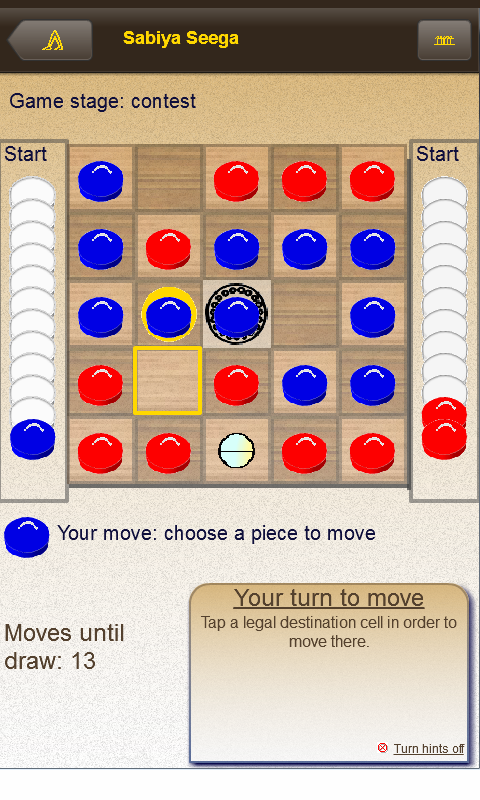

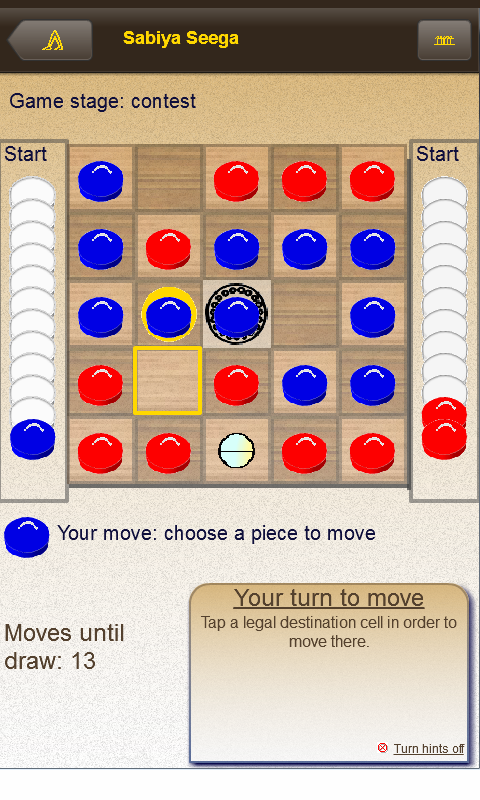

Well, last week saw the release of my new game-app Sabiya Seega, out to various app stores for both Android and Apple phones and tablets. While I can’t say that it has taken the world by storm yet, I have been delighted by a quick response, especially at the iStore and Barnes & Noble. Perhaps people really have been waiting anxiously for this game to appear on their mobile devices! So I thought I’d say a bit more about it here.

Like most board games from the ancient world, we cannot be certain of the rules, and it is a fair guess that there were many local variations rather than a single universally agreed form. Seega boards are nowhere near so commonly found as Senet or Aseb (the Royal Game of Ur), although it has successfully retained a following in parts of Africa through all the years until today. Although the Greeks said they had learned the game in Egypt, direct evidence for this is lacking. Where we do have possible remains of boards – such as in Petra – these are not unambiguous, and might have been used for a different purpose altogether.

What we do know is that the principles of Seega became popular in a range of games across Europe. In particular, the capture method of sandwiching the target counter between two of your own counters appears in games spreading all through the Greek and Roman worlds up eventually to the Vikings.

The original game seems to have been played on several different sized boards – all of odd numbers of cells on a side, so that there is a central cell which in the early stages must be left blank. The first release of Sabiya Seega only allows 5×5 boards, with 12 pieces on each side, but future releases will be more flexible about this.

Something that fascinates me is what role games were thought to have in ancient cultures. Senet, for example, seems to have been strongly linked with religious and spiritual issues, and many of the pictures we have show a tomb occupant engaged in play. Was this just a picture of elite relaxation, or was a direct link seen between the game stages and the progress of the player through the afterlife? Some modern writers think so, suggesting that the game was played by different people with very different aims in mind, from fun or gambling through to religious symbolism and engagement with the other world.

With Seega we cannot be sure, as visual images are scarce. Something that might have made a key difference here is that Seega involves no chance element. Unlike Senet or the Royal Game of Ur, where skill and chance are combined and so even the best of players might suffer ill-fortune, the moves in Seega are completely under the players’ control. Perhaps this set a trend for a mental attitude that inclined towards the military rather than the religious?

So such is unknown about this game, and I have tried to reflect that by providing multiple game options. Players can tweak the settings how they please between games to give themselves different experiences of play.

I hope you enjoy playing Seega – it is available for both Android and Apple phones and tablets from the major app stores. There are even other board or pencil-and-paper versions you might play! Open up your favourite app store and search for Sabiya Seega (or DataScenes Development) and see what you think. For more information navigate to http://apps.datascenesdev.com and follow the links there.

Back to writing – or maybe reviewing – next week!