I spent part of the holiday season exploring a few online tools for visualising the time and/or space of books. There are plenty of these that allow you to hook up a web page to some sort of data source – Google spreadsheets or direct data entry are the favourites – behind the scenes this gets turned into something called JSON which works beautifully with web page displays, but is not very readable… as a user you don’t really care about that though.

For the more technically minded of us, there are freely available code libraries that you can incorporate into your own website (but not into most blogs because of the restrictions that most apply regarding scripts). I will probably look into these sometime as – perhaps inevitably – none of the already-prepared ones quite does what I want. To remind myself, if nobody else, one such library is https://code.google.com/p/timemap/. But more of that another time.

There were two variations I looked at – simple timelines, and timelines which also display related map data for a combined time + space representation. I only considered ones which allowed BC dates since otherwise they would have been entirely useless to me.

Timeline only

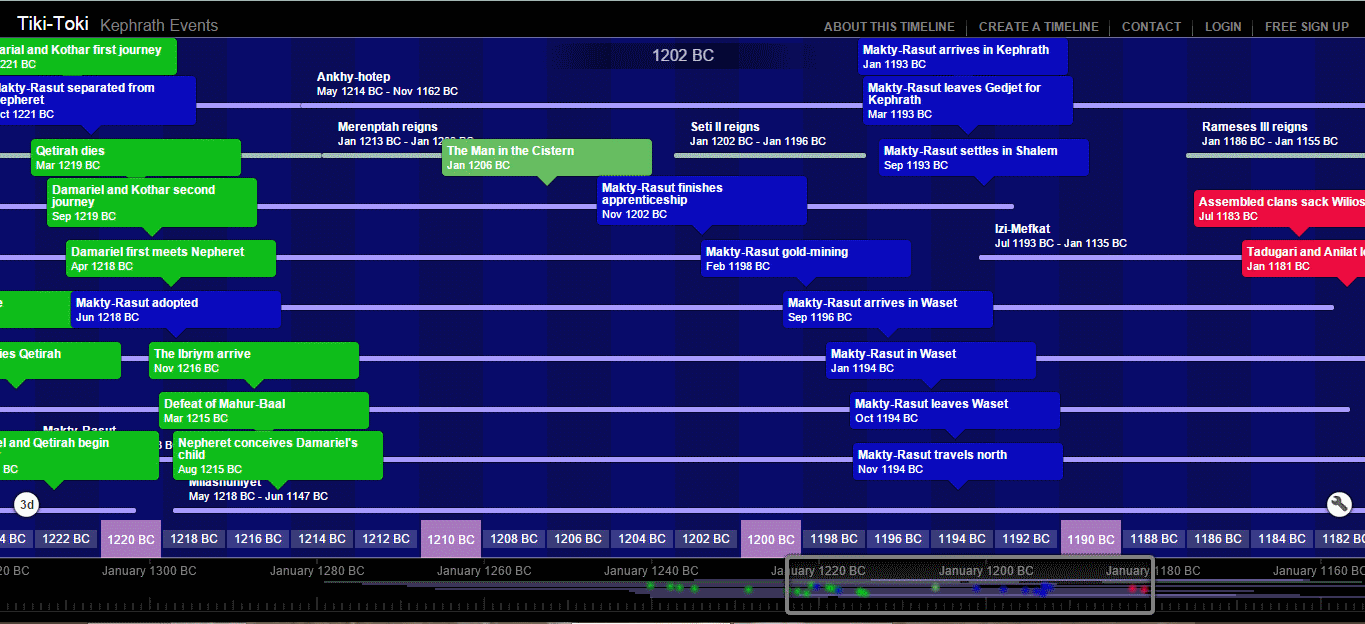

After looking at several I ended up with http://www.tiki-toki.com/timeline/entry/389701/Kephrath-Events/.

After looking at several I ended up with http://www.tiki-toki.com/timeline/entry/389701/Kephrath-Events/.

Yes I know it is a silly domain name, but that’s what you sometimes get online!

Positive things:

- The colour scheme is highly configurable

- You can set up different “categories” and use these to colour code the entries – in my case the colour coding is mainly by book, but also with separate colours for historical and biographical notes

- There are options to change the way the events are displayed – separate stripes per category, different numbers of vertical bands, etc – even a sort of pseudo 3d display

- It is free – at least for a single timeline, though you have to pay if you want to set up multiple timelines

Negative things:

- They don’t let you embed the result in your own web page (unless you pay)

- The display always opens at the first event, which in my case is well before the events that I want people to start with

- There are still things you cannot configure (like text colour)

- Data entry gets progressively more frustrating the more entries you set up (since it is all typed directly into text boxes and the like), and I’m not sure there is an easy way to set up a real data source

- There’s no map

Timeline plus map

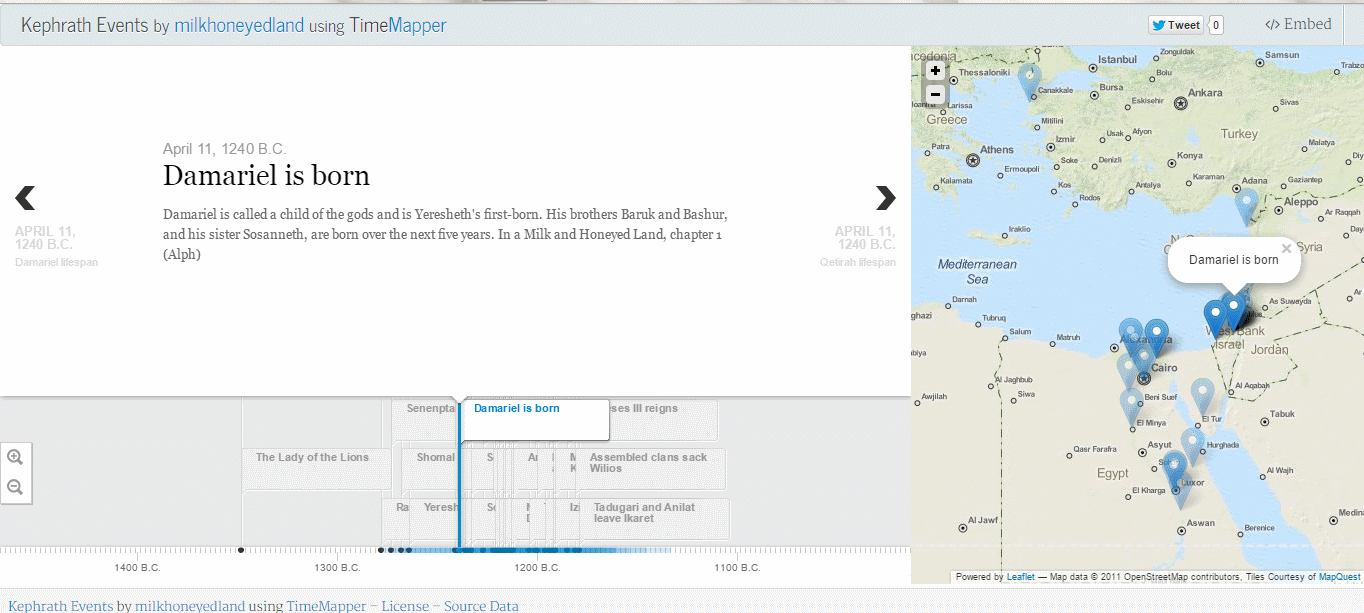

There are not so many of these, and I chose http://timemapper.okfnlabs.org/milkhoneyedland/kephrath-events.

There are not so many of these, and I chose http://timemapper.okfnlabs.org/milkhoneyedland/kephrath-events.

This gets closer to what I wanted, but is still not perfect.

Positive things:

- The map resizes itself automatically to fit your geographic needs

- The integration between timeline and map is pretty good, and you can load the screen at any event you choose

- Data entry scales well since it is based on a Google spreadsheet rather than manual entry

- It is free

- There is an easy way to embed the result into your own web page

Negative things:

- There are very few configurable colour options, and in particular all map pointers are the same colour so you cannot discriminate easily between threads

- The map itself cannot be configured to show less information, so in particular you cannot hide modern placenames

The problem of modern names, boundaries, etc was one which I faced some years ago with a mobile app to explore early alphabetic developments, and found at the time that ESRI maps, unlike Google, can be configured to show only geographic features rather than human infrastructure. This is where the Google timemap library would come in handy… among other things it allows you to switch between different map providers. And I am sure that you can configure the look just however you want. This can be a project for when The Flame Before Us is finished!

Now those of my friends who write historical fiction could quite easily do something similar here – any date range from remote past into the future can be accessed, and the geography of the planet has – for the most part – not changed so very much over the range most of us write about.

And writers of science fiction or fantasy could fairly easily make use of the timeline aspects of this, though I do not yet know if timeline dates can be configured to say something like “Star Date 12345”. However, the map aspect might be a problem. Some books make use of non-standard geography, like erratically appearing islands (such as Borschland) which, as yet, Google and the other map providers have overlooked.

Other books are set on different planets altogether. I guess a truly dedicated writer with the necessary technical skills could write their own map tile server which would define the necessary worlds (rather like Google have done with their Moon and Mars variants of Google Earth).

So where am I going to take this? Well, I think it is a good way to present something about the book. I will be adding in new bits and pieces as they become available and time permits. And later this year I intend putting in the work to customise the map, colours and so on.

But I also think it needs a bit more than just the raw data. Some photos of relevant places would be nice, or maybe links to book extracts or character studies. The timeline, even when enhanced by the map, is only a first step into a visual exploration of the books.

The raw textual material in the Hebrew Bible bearing on Jerusalem is as follows. Judges chapter 1 has two references. In verse 8 we read

The raw textual material in the Hebrew Bible bearing on Jerusalem is as follows. Judges chapter 1 has two references. In verse 8 we read

The typical pattern is to open with a state of stability and peace, which is then disrupted in some way – perhaps by a natural crisis, or by wickedly motivated individuals. The disruption may be presented from several different points of view, depending on the length of the work. The pivotal event is at the centre to resolve the crisis – in some texts it might be a battle, for example, but in others it will be a celebration of a god, nation or individual. Merenptah’s Israel Stele has “A great wonder has occurred for Egypt“. The Hebrew “Song of the Sea” (Exodus 15, first half) has “Who like you among the gods? Yahweh!“. After the central affirmation the situation ‘unwinds’, commonly in symmetric ways to the opening layers, and the setting is restored to peace and stability.

The typical pattern is to open with a state of stability and peace, which is then disrupted in some way – perhaps by a natural crisis, or by wickedly motivated individuals. The disruption may be presented from several different points of view, depending on the length of the work. The pivotal event is at the centre to resolve the crisis – in some texts it might be a battle, for example, but in others it will be a celebration of a god, nation or individual. Merenptah’s Israel Stele has “A great wonder has occurred for Egypt“. The Hebrew “Song of the Sea” (Exodus 15, first half) has “Who like you among the gods? Yahweh!“. After the central affirmation the situation ‘unwinds’, commonly in symmetric ways to the opening layers, and the setting is restored to peace and stability.