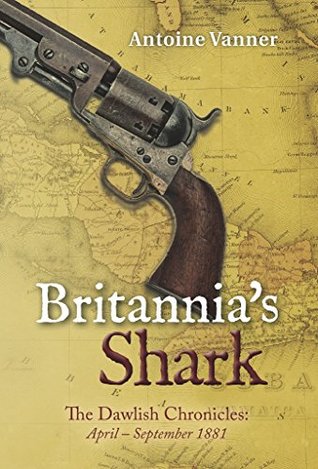

Today I am delighted to welcome Antoine Vanner to the blog, who has kindly answered a number of interview questions. This is a follow-on to my review of Britannia’s Shark a few days ago.

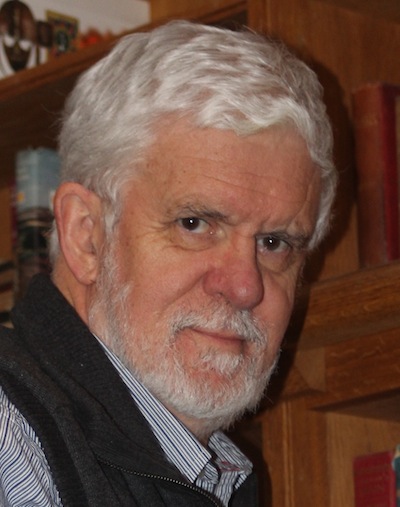

Antoine is the author of (to date) three novels on the life and exploits of a Royal Navy captain of the late 19th century, Nicholas Dawlish.

I have reviewed each of these at

Britannia’s Wolf

Britannia’s Reach

Britannia’s Shark

Q. You write about an unusual period in naval fiction – the late 19th century. What first sparked your interest in this era?

A. There are two parts to the answer, the first related to the period and the second to the naval aspects.

I’m fascinated by the political, social and economic progress made by the Western World in the second half of the 19th century and I’m equally intrigued by the gigantic steps taken by science and technology at the same time. Like most Baby Boomers I had grandparents who had been born and had come to maturity in the last decades of that century and from them I learned enough to regard it as “history you can touch”. The scientific progress – achieved by titanic figures like James Clerk Maxwell, Pasteur, Mendeleev, Darwin, Röntgen, Koch, Ronald Ross, Lord Kelvin and a myriad others – transformed understanding of the world and heroic engineers – such as Edison, Tesla, Marconi, Parsons, Bell, Bessemer, Roebling, Greathead, Bazalgette and many more – established technologies that have flourished and spun off further developments ever since.

I’m fascinated by the political, social and economic progress made by the Western World in the second half of the 19th century and I’m equally intrigued by the gigantic steps taken by science and technology at the same time. Like most Baby Boomers I had grandparents who had been born and had come to maturity in the last decades of that century and from them I learned enough to regard it as “history you can touch”. The scientific progress – achieved by titanic figures like James Clerk Maxwell, Pasteur, Mendeleev, Darwin, Röntgen, Koch, Ronald Ross, Lord Kelvin and a myriad others – transformed understanding of the world and heroic engineers – such as Edison, Tesla, Marconi, Parsons, Bell, Bessemer, Roebling, Greathead, Bazalgette and many more – established technologies that have flourished and spun off further developments ever since.

A parallel revolution occurred in naval technology and it was to have profound political and historic implications not fully recognised at the time. In the 1850s, for example, senior commanders had served in sailing warships in the Napoleonic Wars. Yet officers who entered the service in that decade – such as the later Admiral Lord Fisher – were to create the navy that fought World War 1. They had the vision during their careers to harness developments in metallurgy, hydrodynamics, propulsion, breech-loading artillery, radio, torpedoes and even aircraft. New navies were to arise to challenge British supremacy – those of Germany, Japan and the United States – and in the process contribute to a slide towards the two World Wars in the 20th Century.

Q. The first Dawlish book, Britannia’s Wolf, was set mainly in and around the Black Sea. Britannia’s Reach was largely in South America. The latest, Britannia’s Shark, spans from the Adriatic to the Americas. Is his globe-trotting career typical of officers of his time? How did their experience of other lands and other cultures feed back into English society?

A. It’s remarkable just how much Victorians got about, and not just explorers like Burton, Livingstone, Kingsley and Stanley, but even people we think of as somewhat staid figures. One of my favourite authors, Anthony Trollope, who is always associated with stories of contemporary British society, travelled to Australia, to United States (in wartime and later, crossing the Rockies) the Middle East and South Africa (in Natal just before the Zulu War). Britons and American who could afford it spent holidays in Egypt, and the Holy Land seems to have been thronged with tourists. Some of the most amazing travellers were women – my favourite is Isabella Bird. She was undaunted by rough travel in America, India, Kurdistan, the Persian Gulf, Iran, Tibet, Malaysia, Korea, Japan and China – the list is endless. Her books are massively entertaining and her photographs are superb. And of course military and naval officers got to just about everywhere, either in the line of duty or on private expeditions during leaves of absence.

The result of much of the travel was creation of academic and other institutions in Britain dedicated to the study of foreign culture and languages, and to medical, zoological, botanical and geological research based on insights gained. Those institutions are with us today and in many cases established entire new disciplines.

Q. So, Dawlish is very well travelled, and I know that you are as well. Do you try to personally visit the sites of the stories or rely on more general research? Are the stories sparked by your own travels?

A. The novels published so far, and those in the pipeline, are all based on a combination of a greater or lesser knowledge of the locales and on interest in the historic events in those places in that period. Some of this reflects broad experience of my work and residence, but on occasion it’s necessary to go for much targeted research, either at specific locations, to get the geography right, or to visit museums to see various artefacts. I’ve been to over 50 countries, for residence, work or personal travel, and in every case I’ve made myself familiar with the broad – and sometimes detailed – history. And history spins off stories!

Q. You have often mentioned how the Royal Navy of Dawlish’s era was, of necessity, skilled at working on land as well. Do you see this as a common theme of navies in history? Is there something about a life at sea which promotes a flexible and creative approach to problems?

A. The ad-hoc “naval brigades” who the Royal Navy landed so often, and which ranged in size from a few dozen to several hundred men, were the Rapid Response units of their time. Since radio had not arrived, commanders in remote locations had to be ready to take quick decisions without more senior approval and this bred very self-reliant characters. I suspect that the phenomenon was common in most large navies prior to the invention of wireless. And as regards life at sea then yes, self-reliance is almost a sine qua non. Even today a ship is an isolated, self-sustaining island once it has left port and such self-reliance is needed not only in personal terms, but as regards structure, organisation and discipline. Whether on a Greek trireme or a modern ballistic submarine, each crew member needs to know his or her job perfectly. The price of anything less can be disaster.

Q. Continuing this theme, I have a sense from your writing that you see great continuity between seamen of Dawlish’s age and our own. Looking the other way, do you think this is true of older generations? Would, say, a Napoleonic captain identify with Dawlish? A Viking? A Roman or Phoenician?

A. Externalities – especially technologies – change but human capacities do such much more slowly, if at all. When one reads of the past one is struck by just how professional naval personnel were at all times in the past, seen by the standards of their own time. When one visits a sailing warship like HMS Victory or USS Constitution one is struck by the labyrinthine complexity of their standing and running rigging, by the skill needed to manoeuvre in adverse winds, waves and currents, by the organisation needed to bring the guns into action, sometimes for hours on end. By the standards of the time officers of such vessels needed to be as competent as those on an aircraft carrier today. The same applies to seamen of earlier ages. Given a time machine, and appropriate training opportunities, I suspect that many from the past would come very quickly up to speed on modern warships.

Q. I know that military servicemen have found your writing about war very faithful to their own experience. Have you been caught up in conflict yourself?

A. There is significant military experience in the family, both direct and via in-laws, and some of this very obviously rubs off. I myself have worked in a number of trouble spots and indeed once managed a company in an area torn by a vicious terrorist campaign, in which our operations, and I myself, were targets. One gets used to living with, and planning for, some very nasty risks. And just when I thought it was safe, when I retired about ten years ago, I found myself caught on a personal basis in a murderous attack in Africa in which eight were killed. A 200 yard sprint under AK-47 fire proved Churchill’s alleged statement that “There’s nothing as exhilarating as being shot at – and missed!”

A. There is significant military experience in the family, both direct and via in-laws, and some of this very obviously rubs off. I myself have worked in a number of trouble spots and indeed once managed a company in an area torn by a vicious terrorist campaign, in which our operations, and I myself, were targets. One gets used to living with, and planning for, some very nasty risks. And just when I thought it was safe, when I retired about ten years ago, I found myself caught on a personal basis in a murderous attack in Africa in which eight were killed. A 200 yard sprint under AK-47 fire proved Churchill’s alleged statement that “There’s nothing as exhilarating as being shot at – and missed!”

Q. I find your blog http://dawlishchronicles.blogspot.co.uk/ a fascinating compendium of naval history. Could you tell us a little about your research for this and the sources behind it?

A. I thought initially as the blog being somewhere where I could post the odd article, based either on personal experience, or on some aspect of my general historical knowledge, or on information arising from my book-focussed research which I might not use directly in the actual writing. I found it a pity to let the latter go to waste. The response to the blog turned out to be amazing – people really like it and the readership numbers continue to grow. My articles aren’t detailed academic ones, but rather more like the sort of informal story-telling one might indulge in when relaxing with friends. I don’t think I’ve blogged about anything I didn’t know something about before – though sometimes very superficially. Remember that in over 60 years of reading, and with a reasonable memory, one accumulates a lot of information – but the items still often need a fair amount of library and internet research. The occasional very personal pieces – like those I wrote about having toured Syria just before the war there, or visiting the Alzhir Women’s Gulag in Kazakhstan – can be quite emotionally draining to write.

Q. Tell us a little about your writing process – research, drafting, polishing etc.

A. I’m now writing my seventh novel, though only three have been published so far. One of them is a non-Dawlish novel dealing with contemporary African issues. It’s quite a sombre book and reflects personal experience. I’m uncertain as to when and how to publish it. As regards the Dawlish Chronicles I like to have one book at least, and indeed two at present, “on the back burner”. By this I mean that I finish a first draft, correct and rewrite as necessary, then lay it aside while I’m writing the next one. I find that though I don’t read the back-burner novel for the nine months or so that it takes me to write the next one, my subconscious keeps challenging it as regards plot, action and sequence. I jot down any conscious insights also. When I come back to do my next revision after some nine or ten months I find myself reading very critically to start and Imay make very significant changes indeed. The dictum that “writing is rewriting” is always valid and in extreme cases one must be prepared to delete even entire chapters, write new ones, and restructure. The fourth Dawlish Chronicles novel will be getting the full revision treatment in mid-2015, aimed at publication in the fourth quarter.

Q. I suspect that you are well on with the next Dawlish novel, but can’t imagine you want to tell us too much about it yet! Can you whet our appetite by outlining some of the wider political scene that faced the Royal Navy at this time?

A. Given the ramparts of confidentiality that the shadowy Admiral Topcliffe erected around the events in questiob, and despite the cooperation of official archivists and the benefits of the Freedom of Information Act, I would hesitate to answer that one just yet! Some embarrassing incidents are involved for which a once-hostile, now-friendly nation was responsible and I’ll have to tread very carefully. But with luck, I hope all difficulties can be overcome and the full story can finally be told in about ten months’ time!

And finally – Thanks Richard for taking the time to interview me! It’s been as much a pleasure to answer your questions as it is to know you and your work!

And finally – Thanks Richard for taking the time to interview me! It’s been as much a pleasure to answer your questions as it is to know you and your work!

The pleasure is mine, Antoine! Check out online information about Antoine by following the links below:

I’m fascinated by the political, social and economic progress made by the Western World in the second half of the 19th century and I’m equally intrigued by the gigantic steps taken by science and technology at the same time. Like most Baby Boomers I had grandparents who had been born and had come to maturity in the last decades of that century and from them I learned enough to regard it as “history you can touch”. The scientific progress – achieved by titanic figures like James Clerk Maxwell, Pasteur, Mendeleev, Darwin, Röntgen, Koch, Ronald Ross, Lord Kelvin and a myriad others – transformed understanding of the world and heroic engineers – such as Edison, Tesla, Marconi, Parsons, Bell, Bessemer, Roebling, Greathead, Bazalgette and many more – established technologies that have flourished and spun off further developments ever since.

I’m fascinated by the political, social and economic progress made by the Western World in the second half of the 19th century and I’m equally intrigued by the gigantic steps taken by science and technology at the same time. Like most Baby Boomers I had grandparents who had been born and had come to maturity in the last decades of that century and from them I learned enough to regard it as “history you can touch”. The scientific progress – achieved by titanic figures like James Clerk Maxwell, Pasteur, Mendeleev, Darwin, Röntgen, Koch, Ronald Ross, Lord Kelvin and a myriad others – transformed understanding of the world and heroic engineers – such as Edison, Tesla, Marconi, Parsons, Bell, Bessemer, Roebling, Greathead, Bazalgette and many more – established technologies that have flourished and spun off further developments ever since. A. There is significant military experience in the family, both direct and via in-laws, and some of this very obviously rubs off. I myself have worked in a number of trouble spots and indeed once managed a company in an area torn by a vicious terrorist campaign, in which our operations, and I myself, were targets. One gets used to living with, and planning for, some very nasty risks. And just when I thought it was safe, when I retired about ten years ago, I found myself caught on a personal basis in a murderous attack in Africa in which eight were killed. A 200 yard sprint under AK-47 fire proved Churchill’s alleged statement that “There’s nothing as exhilarating as being shot at – and missed!”

A. There is significant military experience in the family, both direct and via in-laws, and some of this very obviously rubs off. I myself have worked in a number of trouble spots and indeed once managed a company in an area torn by a vicious terrorist campaign, in which our operations, and I myself, were targets. One gets used to living with, and planning for, some very nasty risks. And just when I thought it was safe, when I retired about ten years ago, I found myself caught on a personal basis in a murderous attack in Africa in which eight were killed. A 200 yard sprint under AK-47 fire proved Churchill’s alleged statement that “There’s nothing as exhilarating as being shot at – and missed!” And finally – Thanks Richard for taking the time to interview me! It’s been as much a pleasure to answer your questions as it is to know you and your work!

And finally – Thanks Richard for taking the time to interview me! It’s been as much a pleasure to answer your questions as it is to know you and your work!