:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/64886612/Screen_Shot_2019_07_31_at_2.46.38_PM.0.png)

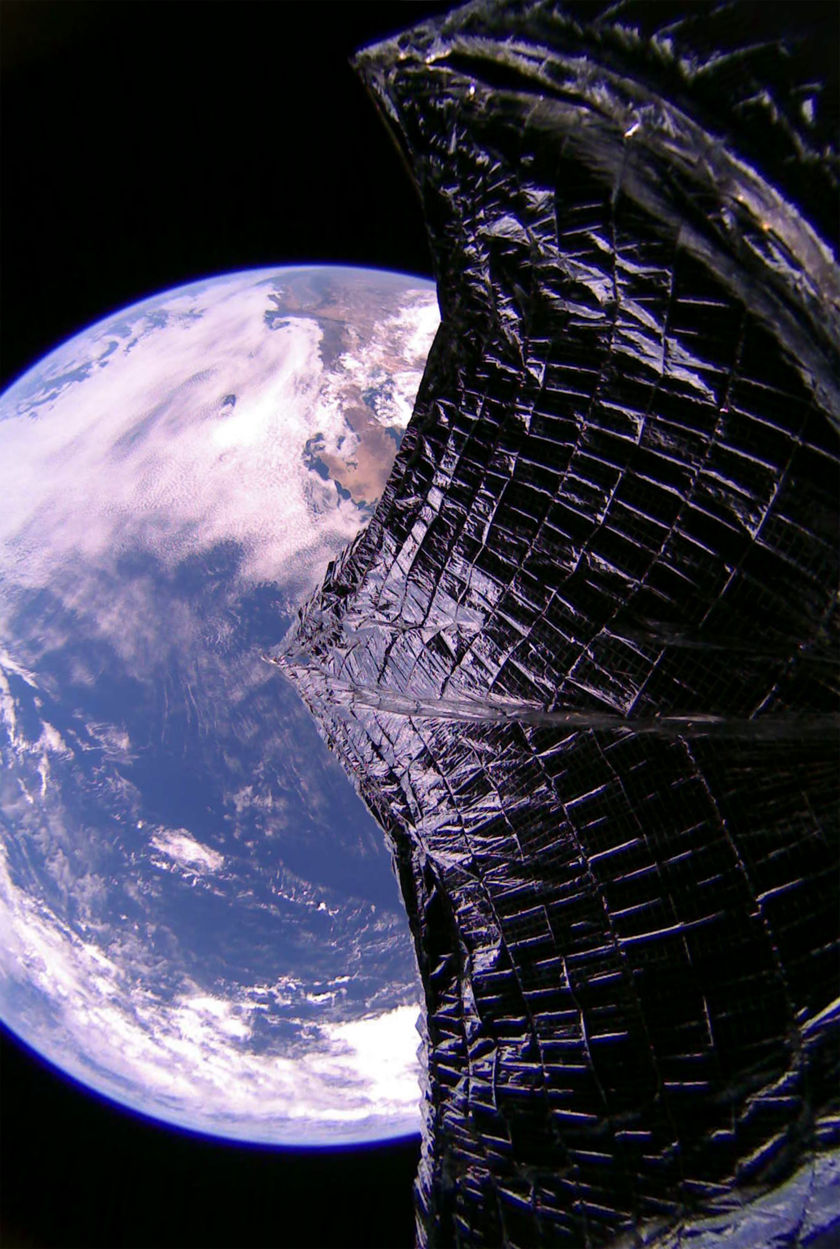

A few weeks ago I blogged about lightsails, and in particular mentioned the Planetary Society’s spaceship LightSail 2, which was launched specifically in order to test this technology. The idea was relatively simple – get a small satellite, about the size of a cereal box, into earth orbit, then deploy the sail and see whether the orbit can be controlled using solar radiation alone.

Now, this isn’t really the sphere of operations that you would generally consider a lightsail – they function at their best when on a long journey and can build up momentum second by second. Here in Earth orbit, the overall effect is to make the orbit more elliptical – one part of the orbit is raised in altitude, but another part is lowered, and at some point the little satellite will encounter too much resistance from the atmosphere and will come down, burning up as it does so. The advantage of doing it so close to home is that there is hardly any signal lag, so controlling the sail’s angle, and tracking the consequences of changes, is very much easier.

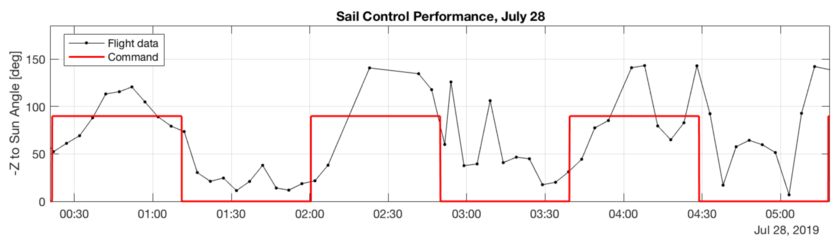

To cut a long story short, the experiment worked. After a couple of weeks, the orbit had been raised around 3km. That doesn’t sound much, but it’s enough to show that the whole thing is controllable. A lot of analysis has been carried out on the orbital changes – you can imagine that as the satellite goes around the Earth, the angle relative to the sun is constantly changing. It was important to show that the observed changes were the result of ground commands, not just the random effects of sunlight shining at odd angles. So the orbital data has been heavily scrutinised, and came out successfully at the end.

The extended mission period also gave the ground control team experience in how to best use the constantly changing angle. By the end of those two weeks of deployment, they had learned what worked well and what didn’t. It’s good experience for this kind of mission, but as I said earlier, a more realistic use-case would be to go on a transfer trajectory to a more remote destination – say Mars – and on such a journey. the angle between sail and sun would not vary anywhere near so much.

The experiment will continue through the rest of August, maybe a bit longer, and anyone who wants to see the current status can go to http://www.planetary.org/explore/projects/lightsail-solar-sailing/lightsail-mission-control.html which gibves all kinds of geeky information as well as a neat map showing the current location of LightSail 2.

While talking about space news, it’s certainly worth mentioning India’s Chandrayaan 2 mission. That has just left Earth orbit, and aims to soft-land about 600km from the Moon’s south pole in about a week. The approach used is similar to that of Israel’s Beresheet, in which a series of gradually elongated elliptical orbits around the Earth is eventually traded at a transfer point to a series of gradually diminishing orbits around the Moon. The lunar south pole is thought to be the most promising location for water ice, lurking on the surface in deep shadow areas and hence available very rapidly for human use. Proving that this really is – or maybe is not – the case is an important step towards building a permanent settlement on the Moon. The landing itself is scheduled for early September. The main mission web site is at https://www.isro.gov.in/chandrayaan2-home-0 and here’s a short video describing it.

Hopefully I shall be saying some more about that in September. But inevitably at present, the question for this blog is what these events have to do with fiction. My own vision of the future exploration of the solar system has spaceships using an ion drive rather than lightsails, since I expect these to be faster, and more effective in the volume outside the asteroid belt, as solar radiation drops off. But I can easily image automated lightsail ships being used for cargo which is not time-critical – not unlike how we send some freight by air and some by water today.

But the lunar south pole has been suggested many times as a good place to build a base, going back at least to Buzz Aldrin’s Encounter with Tiber. I makes perfect sense to me, and it would be great if Chandrayaan 2 was able to directly confirm that water ice is there.