This is the first part of two, in which I look at the ways in which books show their age.

I read a lot of science fiction, and I watch a fair number of science fiction films and TV series. The latest addition is Star Trek Discovery, the latest offering in that very-long-running universe. For those who don’t know, it’s set in a time frame a few years before the original series (the one with Captain Kirk), and well after the series just called Enterprise.

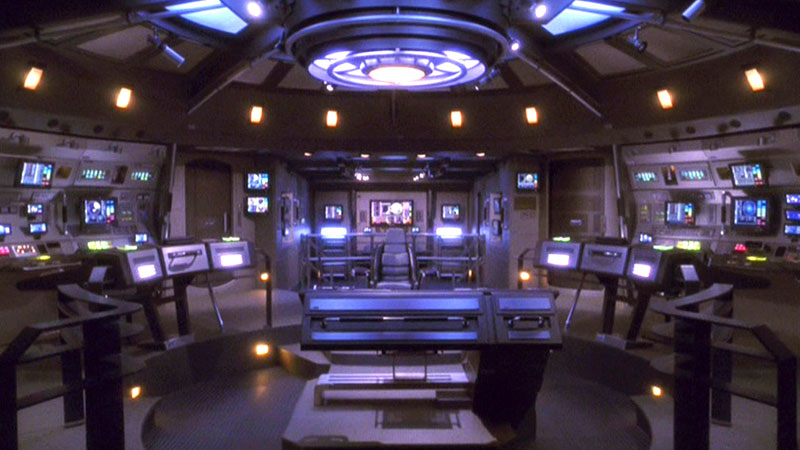

Inevitably the new series has had a mixed reception, but I have enjoyed the first couple of episodes. But the thing I wanted to write about today was not the storyline, or the characters, but the presentation of technology. The bridge of the starship Shenzhou looked just like you’d imagine – lots of touch screen consoles, big displays showing not just some sensor data but also some interpretive stuff so you could make sense of it. And so on. It looked great – recognisable to us 21st century folk used to our own touch screen phones and the like, but futuristic enough that you knew you couldn’t just buy it all from Maplin.

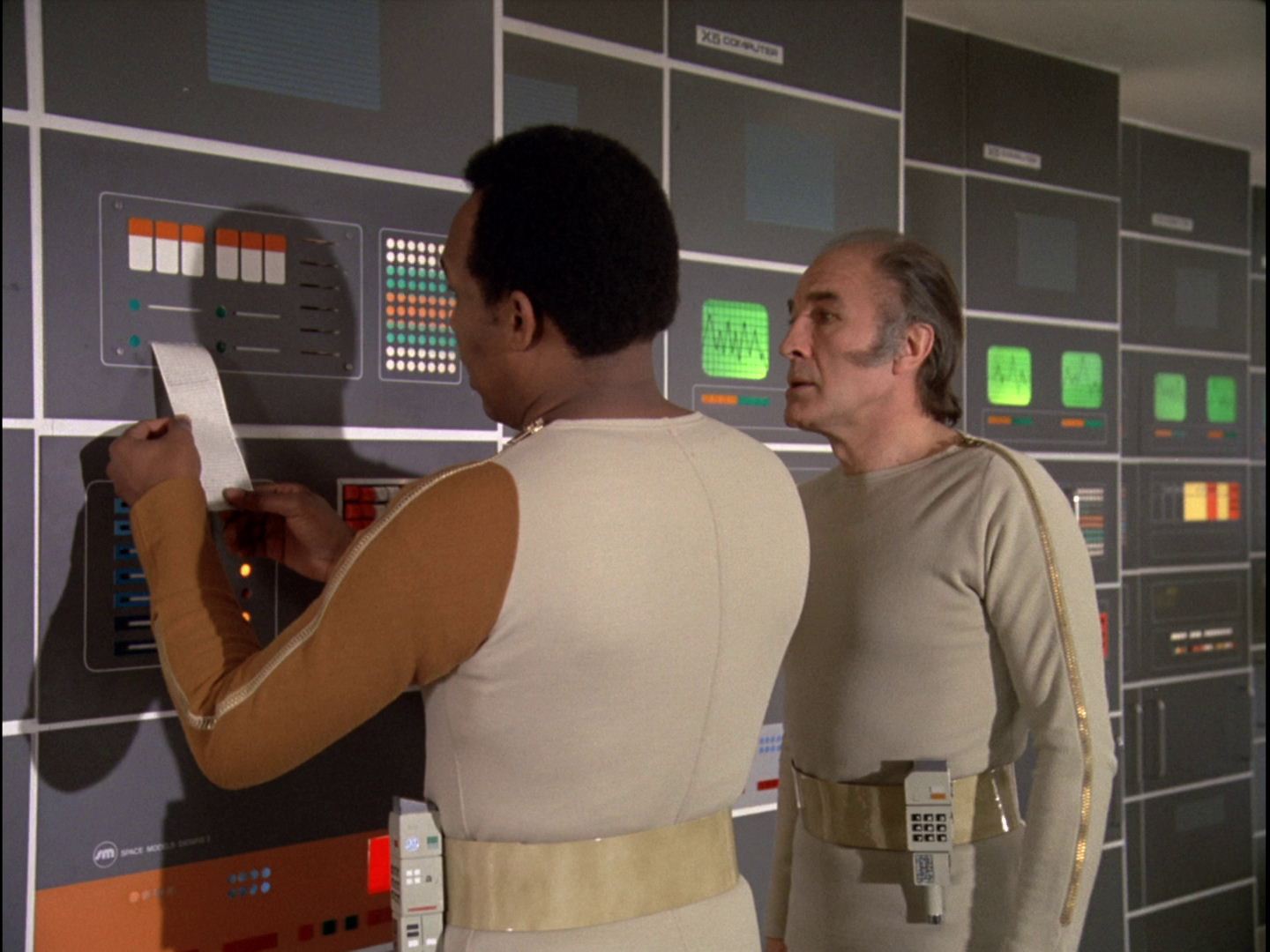

But herein lies the problem. Look back at an old episode of the original series, and the Enterprise bridge looks really naff! I dare say that back in the 1960s it also gave the impression of “this is cool future stuff”, but it certainly doesn’t look as though it’s another decade or so on from the technological world of Discovery.

Basically, our ability to build cool gadgets has vastly outstripped the imagination of authors and film makers. Just about any old science fiction book suffers from this. You find computers on board spaceships which can think, carry out prodigiously complex calculations, and so on, but output their results on reams of printed paper. Once you start looking, you can find all manner of things like this.

Now, on one level this doesn’t matter at all. The story is the main thing, and most of us can put up with little failures of imagination about just how quickly actual invention and design would displace what seemed to be far-fetched ideas. On the whole we can forgive individual stories for their foibles. If it’s a good story, we don’t mind the punched-card inputs, paper-tape outputs, and so on. We accept that in the spirit that the author intended. Also, many authors are not so very interested in the mechanics of the story, or how feasible the science is, but in different dimensions. How might people react in particular circumstances? What are the moral dimensions involved? What aspects of the story resonate most strongly with present-day issues?

The particular problem that Discovery has is simply that it is part of a wider set of series, and we already thought we knew what the future looked like! A particular peril for any of us writing a series of books.

Now it’s not just science fiction that can be left behind by the march of events. Our view of history can, and has, changed as new evidence comes to light. Casual assumptions that one generation makes about past societies, interactions, and chronology may be turned over a few years down the line. Sometimes we look at the ways in which older authors presented things and cringe. Historical fiction books might easily be overtaken by research and deeper understanding, just as much as science fiction. It’s a risk we all face.

Next time – some thoughts about my own science fiction series, Far from the Spaceports, and the particular things in that story that might get left behind. And also, the particular problems of writing about the near-future.

One thought on “Left behind by events, part 1”