Elon Musk, founder and CEO of SpaceX, has made no secret of his plans for facilitating a colony on Mars for a long time now. But last September, in a public presentation, he explained it all in considerably more detail. The reasoning, and the raw logistical figures behind it, are still available. His credibility is built around the SpaceX programme. This in turn is based on a concept of reusing equipment rather than throwing it away each launch, and it has had a string of successes lately. The initial booster stage now returns to a landing platform, there to go through a process which recommissions it for another launch.

Quite apart from any recycling benefits, this then allows SpaceX to seriously undercut other firms’ prices of putting satellites into orbit. It still couldn’t be called cheap – one set of figures quotes $65 million – but that’s only about one sixth of the regular cost. If you’re happy to know that your equipment is going into orbit on a rocket that is not brand new, it’s a huge saving. Every successful launch, return to base, and relaunch, adds to buyers’ confidence that the procedure can be trusted.

But the big picture goes well beyond Earth orbit. Musk believes that the best way to mitigate the risks of life on Earth – global warming, conflict, extremist views of all kinds, and so on – is to spread out more widely. In a recent lecture, Stephen Hawking has said essentially the same thing. And in Musk’s vision, Mars is a better bet than the moon for this, for a whole cluster of reasons including the presence of an atmosphere (albeit a thin one compared to here) and a greater likeness to Earth in terms of gravity and size.

So reusable rockets into Earth orbit are simply a starting point. Once you have a reasonably-sized fleet of such things, you can build larger objects already in space, and fly them over to Mars when the orbital positions are ideal. The logic of gravitational pull around a planet means that the hardest, and most energy-intensive part is needed to get you from the surface up to a stable orbit. Once there, much gentler and longer-lasting means of propulsion will get you onward bound.

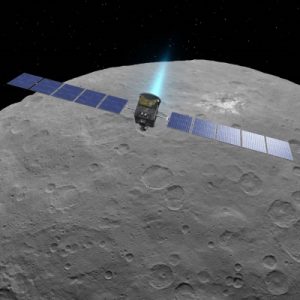

To take a contemporary situation, NASA’s Dawn probe is currently orbiting the asteroid Ceres. Its hydrazine fuel, which powers the little manoeuvring and attitude thrusters, is nearly exhausted. The mission control team are trying to decide on the best course of action. In its current high orbit only a few months of fuel remain. A closer orbit, which would give better quality pictures, would use it up in a matter of weeks. But using the main ion drive, a different power source altogether, to go somewhere else would probably give a few years of science. Fairly soon we should hear which option they have chosen, and where they consider the best balance is between risk and reward. The message for here is that staying close to a planet, or taking off from one, is costly in terms of fuel.

So Musk reckons that over the course of a century or so, he can arrange transportation for a million Martian colonists. In terms of grand sweep, it is so far ahead of anyone else’s plans as to seem impossible at first sight. But if all goes according to his admittedly ambitious plan, the first of many journeys could take place ten years from now. He – and I for that matter – might not live to see the Martian population reach a million, but he certainly expects to see it firmly established.

With Far from the Spaceports, its sequel Timing, and the work-in-progress provisionally called The Authentication Key, I deliberately did not fix a future date. It’s far enough ahead of now that artificial intelligence is genuinely personal and relational – sufficiently far ahead that it is entirely normal for a human investigator to be partnered long-term on an equal basis with an AI persona. None of the present clutch of virtual assistants have any chance at all of this, and my guess is that we are talking many generations of software development before this could happen. It’s also far enough ahead that there are colonies in many locations – certainly out as far as the moons of Saturn, and I am thinking about a few “listening post” settlements further out (watch this space – the stories aren’t written yet!). However, I hadn’t really thought in terms of a million colonists on Mars, and it may well be that, as happens so often in science fiction, real events might overtake my scenario a lot quicker than I thought likely.

Back with Musk’s proposal, one obvious consequence of the whole reuse idea is that the cost per person of getting there drops hugely. This buy-in figure is typically quoted as something like $10 billion. But the SpaceX plan drops this down to around $20,000 – cheaper than the average house price in the UK. I wonder how many people, given the chance, would sell up their belongings here in exchange for a fresh start on another planet?

I was wondering what image to finish with, and then came across this NASA/JPL picture of the Mars Curiosity Rover as seen from the Mars Orbiter (the little blue dot roughly in the middle)… a fitting display of the largeness of the planet compared to what we have sent there so far.