Being brought up in the south of England, I had always assumed that King Arthur was basically a southerner. After all, there was Tintagel, Glastonbury, even Winchester, though I knew from an early age that the round table hanging in the castle there had no real connection with him (dendrochronology has set a date around 1275). If I thought about the north at all with reference to Arthur, it was only that maybe he’d gone up there once or twice to trounce some band of malcontents.

But then, rather later, I discovered a strong Welsh connection, and my perspective started to shift a little. I found out that more places, over most of the country, had a claim to Arthurian material, and the southern homeland idea got seriously knocked.

Of course, Arthur is a national symbol, irrespective of any historical reality, so it is natural that associations would be nationwide. And it’s clear that some suggested links are wildly speculative, presumably made by hopeful locals wanting to be attached somehow to the person of the king. But not all of them can be dismissed so quickly.

I’m going to talk in this post and the next about a few links up in Cumbria. Until recently the Lake District had been completely off my Arthurian map, but no longer. But calling it The Lake District brings to mind quiet walks by placid waters, and this is only half of the story of the region. The names Cumbria or Rheged evoke a much more robust image. Until comparatively recently, the area was better known for its rugged and apparently impenetrable mountains, than its placid waters. In 1724, Daniel Defoe wrote that it was “bounded by a chain of almost unpassable mountains which, in the language of the country, are called fells“. So what better place could there be to symbolise the wild unconquered parts of the land?

One of the two easy routes in to the wild heart of the region is from the Eden Valley, via Penrith (the other is up north from Kendal along the shores of Windermere). And indeed, signs of Arthurian connections begin in the Eden Valley. A few miles south and east of Penrith is Pendragon Castle, built, according to legend, by Uther Pendragon, the father of King Arthur. Allegedly Merlin tried to alter the course of the River Eden to make a moat, but his powers were insufficient, and the river stayed where it was. Perhaps with a little more historical footing, Uther is said to have died there after some of his Saxon enemies poisoned the well.

Closer to Penrith is the Neolithic henge known as King Arthur’s Table. Of course the monument itself is vastly older than any probable time of Arthur – probably about 2500 years older. In its day, and long after, it would have been a stunning sight – it is some 90m across, originally with two entrances though one has been obliterated by modern buildings and a road. I can easily imagine a post-Roman leader stopping by to establish some link with ancestral glories. Much later, the site was linked explicitly to Arthur when it was believed that the circular space was used for jousting. In fact we have no idea what the original purpose was, but the area has several henges within a small area, so was presumably a significant location to our remote ancestors (the second henge in the old engraving is long since lost, but nearby Mayburgh Henge still remains).

After that, move a few miles south-west to Ullswater, arriving first at Pooley Bridge. It’s an easier and more obvious route to follow into the hills than today’s A66, although the trail along the 10km of the lake ends in a series of abrupt and dramatic valley ends. Ullswater is one of the longest and deepest of the Cumbrian lakes, and has its own set of monster-in-the-deep tales, reported from early times through to modern visitors. But let’s stick reasonably close to Arthur.

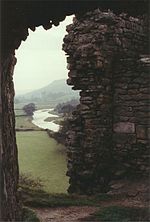

At the northern end of the lake, not far from Pooley Bridge, is Tristamont, or Trestamount, shown on many maps as Hodgson Hill. Local legend has it that this was the burial place of Tristan. Now most of the Arthurian stories present Tristan as a Cornishman by birth (born of Elizabeth to Meliodas, king of the lost land of Lyonesse), but linguistically the name can be linked to Old Welsh, and so directly to the Cumbric language. So a connection with the north-west is far from impossible. The idea of an actual castle, not just a grave, goes back to the antiquarian Rev Machell, who in the 1630s described walls and fortifications here. Now, although it is true that many standing stones and ancient walls in the region have been robbed for building, modern archaeologists are very sceptical that Machell recorded anything more than natural deposits of glacial rock. Under the right conditions, these can indeed look artificial. About the only definite sign of human construction is a ditch around the east side of this hill.

From medieval times – much later than any original King Arthur, though broadly consistent with his reimagining in courtly chivalric terms – we have the tale of Sir Eglamore and his fiancee Emma, probably originating from somewhere around the 13th century. They lived near the waterfall at Aira Force, but the knight was absent on the Crusades for a very long time. Returning unexpectedly, he startled Emma as she was sleep-walking, so that she slipped down the waterfall to her death. Eglamore lived out his days as a hermit beside the falls. It’s a very Arthurian tale, even if not directly linked to the tradition.

So that’s got some of the peripheral details out of the way – next time I’ll be looking at the central details surrounding Arthur’s death and the Lady of the Lake…