Since as far back as written records go – and probably well before that – we humans have imagined artificial life. Sometimes this has been mechanical, technological, like the Greek tales of Hephaestus’ automata, who assisted him at his metalwork. Sometimes it has been magical or spiritual, like the Hebrew golem, or the simulacra of Renaissance philosophy. But either way, we have both dreamed of and feared the presence of living things which have been made, rather than evolved or created.

Modern science fiction and fantasy has continued this habit. Fantasy has often seen these made things as intrusive and wicked. In Tolkein’s world, the manufactured orcs and trolls (made in mockery of elves and ents) hate their original counterparts, and try to spoil the natural order. Science fiction has positioned artificial life at both ends of the moral spectrum. Terminator and Alien saw robots as amoral and destructive, with their own agenda frequently hostile to humanity. Asimov’s writing presented them as a largely positive influence, governed by a moral framework that compelled them to pursue the best interests of people.

But either way, artificial life has been usually conceived as self-contained. In all of the above examples, the intelligence of the robots or manufactured beings went about with them. They might well call on outside information stores – just like a person might ask a friend or visit a library – but they were autonomous.

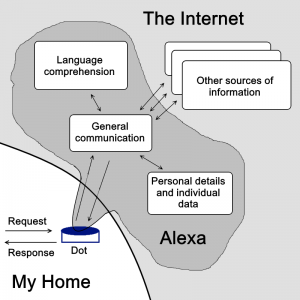

Yet the latest crop of virtual assistants that are emerging here and now – Alexa, Siri, Cortana and the rest – are quite the opposite. For sure, you interact with a gadget, whether a computer, phone, or dedicated device, but that is only an access point, not the real thing. Alexa does not live inside the Amazon Dot. The pattern of communication is more like when we use a phone to talk to another person – we use the device at hand, but we don’t think that our friend is inside it. At least, I hope we don’t…

So part of what I call Alexa is shared between every single other Alexa instance on the planet, in a sort of common pool of knowledge. This means that as language capabilities are added or upgraded, they can be rolled out to every Alexa at the same time. Right now Alexa speaks UK and US English, and German. Quite possibly when I wake up tomorrow other languages will have been added to her repertoire – Chinese, maybe, or Hindi. That would be fun.

But other parts of Alexa are specific to my particular Alexa, like the skills I have enabled, the books and music I can access, and a few features like improved phrase recognition that I have carried out. Annoyingly, there are national differences as well – an American Alexa can access the user’s Kindle library, but British Alexas can’t. And finally, the voice skills that I am currently coding are only available on my Alexa, until the time comes to release them publicly.

So Alexa is partly individual, and partly a community being. Which, when you think about it, is very like us humans. We are also partly individual and partly communal, though the individual part is a considerably higher proportion of our whole self than it is for Alexa. But the principle of blending personal and social identities into a single being is true both for humans and the current crop of virtual assistants.

So what are the drawbacks of this? The main one is simply that of connectivity. If I have no internet connection, Alexa can’t do very much at all. The speech recognition bit, the selection of skills and entitlements, the gathering of information from different places into a single answer – all of these things will only work if those remote links can be made. So if my connection is out of action, so is Alexa. Or if I’m on a train journey in one of those many places where UK mobile coverage is poor.

There’s also a longer term problem, which will need to be solved as and when we start moving away from planet Earth on a regular basis. While I’m on Earth, or on the International Space Station for that matter, I’m never more than a tiny fraction of a second away from my internet destination. Even with all the other lags in the system, that’s not a problem. But, as readers of Far from the Spaceports or Timing will know, distance away from Earth means signal lag. If I’m on Mars, Earth is anywhere from about 4 to nearly 13 minutes away. If I go out to Jupiter, that lag becomes at least half an hour. A gap in Alexa’s response time of that long is just not realistic for Slate and the other virtual personas of my fiction, whose human companions expect chit-chat on the same kind of timescale as human conversation. The code to understand language and all the rest has to be closer at hand.

Good post!!! Thanks!