Today’s basic element is Air. Totally necessary for life, but invisible in its natural state, air is easy to forget until you suddenly feel the lack of it. Human societies in the past have by and large recognised air by means of its effects – the refreshing breath of wind on a still day, the almost-living force in the sails of a boat, or the abrupt violence of a storm. John’s Gospel records Jesus saying, “The wind blows where it wants to. You hear its sound, but you don’t know where it comes from or where it is going“. In ancient Egypt, the god Shu was the personified layer of air which separated earth and sky, and was one of the first two gods, along with his sister Tefnut, moisture, to be created from the breath of the original creator.

The perceived link between wind, breath, and spirituality has fascinated people for millennia. From Hebrew ruach to Taoist ch’i, the movement of air in and out of the body has often been considered to be a mirror to the mysterious movement of the divine around the things of the world.

But for all these more esoteric interpretations, air has also shaped human society in very concrete ways. We cannot comfortably live too high up a mountain without generations of adaptation. We cannot survive underwater for more than a few minutes without carrying a portable air supply. Air pollution causes ill health, demoralisation, and death. The polluting agent may be visible, like the London smogs of a century ago, or Delhi or Beijing today. Or it may be invisible, like the chemical agents which still degrade London’s air quality to unacceptable levels. Allegedly, NO2 and other particulate pollutants in London alone cause several thousand additional deaths, and cost the economy billions every year. The city has a plan to systematically reduce pollution to safe quantities, but it will take some 15 years to achieve this – always assuming that the political will to do so remains. For the meantime, most global cities struggle with issues of air quality.

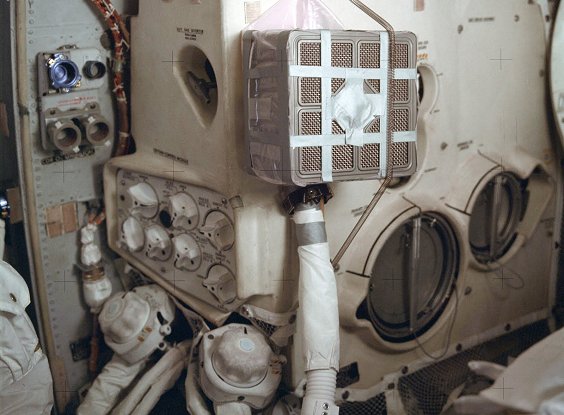

What of the hypothetical future of Far from the Spaceports? Air in its natural state is a very scarce resource in the solar system at large. If and when we colonise other places, one of the first tasks will be to ensure adequate breathable air is available. Now, it is a routine task to remove things like carbon dioxide and monoxide from air – after all, green plants have been doing it pretty well for a long time, and imitating this is an obvious thing to do. I’m sure many of us remember the improvised CO2 scrubber that helped save the lives of the Apollo 13 astronauts.

But any recycling tool like this relies on some sort of chemical transfer, and eventually the chemicals will need replacement. And any system is going to be less than 100% efficient, and what with occasional leakage from airlocks and other seams, the air and oxygen levels will decrease… and need replacing.

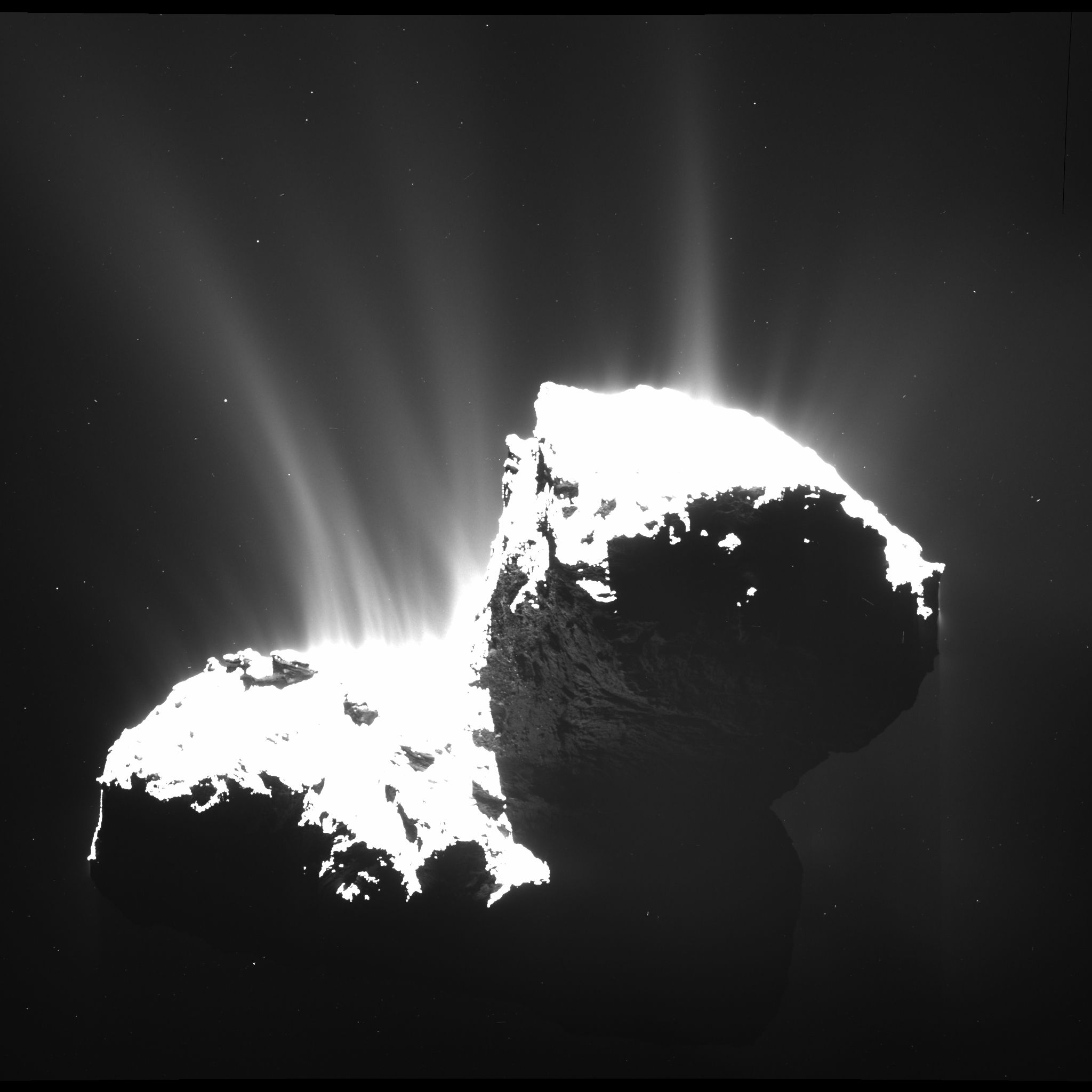

Fortunately, oxygen is the third most abundant element in the solar system (after hydrogen and helium). It can be found bound up in various rocks, as well as wherever water ice can be found – which as we saw last time is pretty much everywhere we look. One of the many surprises of the ESA Rosetta mission to comet 67P was the realisation that it was spewing considerable volumes of water – and hence oxygen – into space as it warmed up.

So acquiring an oxygen supply is not a major problem, at least for many of the locations I hypothesise in the book. But nevertheless, finding, securing and keeping fresh a reliable air supply would be near the top of the task list of the first settlers.

Next time – Light