I’ve been thinking for a little while now about reading and writing, and decided to convert those thoughts into a blog post. I used to reckon that reading and writing were two sides of the same coin. We teach them at broadly the same time, and it seems natural with a child to talk through the physical process of making a letter shape at the same time as learning to recognise it on a page.

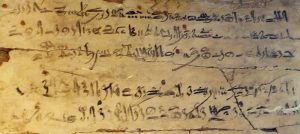

But lately, I’ve been reconsidering this. My thinking actually goes back several years to when I was studying ancient Egyptian. It is generally understood that alongside the scribes of Egypt – who had a good command of hieroglyphic and hieratic writing, plus Akkadian cuneiform and a few other written scripts and a whole lot of technical knowledge besides – there was a much ĺarger group of people who could read reasonably well, but not write with fluency or competence. A few particularly common signs, like the cartouche of the current pharaoh, or the major deity names, would be very widely recognised even by people who were generally illiterate. You see this same process happening with tourists today, who start to spot common groups of Egyptian signs long before they could dream of constructing a sentence.

The ability to write is far more than just knowing letter shapes. You need a wide enough vocabulary to select the right word among several choices, to know how to change each word with past or future tense, or number of people, or gender. You need background knowledge of the subject. You need to understand the conventions of the intended audience so as to convey the right meaning. In short, learning to write is more demanding than learning to read (and I’m talking about the production of writing here, not the quality of the finished product).

Roll forward to the modern day, and we are facing a slightly different kind of question. The ability to read is essential to get and thrive in most jobs. Or to access information, buy various goods, or just navigate from place to place. I’m sure it is possible to live in today’s England without being able to read, but it will be difficult, and all sorts of avenues are closed to that person.

But the ability to write – by which I mean to make handwriting – is, I think, much more in doubt. Right now I’m constructing this blog post in my lunch hour on a mobile phone, tapping little illuminated areas of the screen to generate the letters. In a little while I’ll go back to my desk, and enter characters by pressing down little bits of plastic on a keyboard. Chances are I’ll be writing some computer code (in the C# or NodeJS computer languages, if you’re curious) but if I have to send a message to a colleague I’ll use the same mechanical process.

Then again, some of my friends use dictation software to “write” emails and letters, and then do a small amount of corrective work at the end. They tell me that dictation technology has advanced to the stage where only minor fix-ups are needed. And, as most blog readers will know, I’m enthusiastic about Alexa for controlling functionality by voice. Although writing text of any great length is not yet feasible on that platform, my guess is that it won’t be long until this becomes real.

All of this means that while the act of reading will most likely remain crucial for a long time to come, maybe this won’t be true of writing in the conventional sense. Speaking personally, hand-writing is already something I do only for hastily scribbled notes or postcards to older relatives. Or occasionally to sign something. The readability of my hand-writing is substantially lower than it used to be, purely because I don’t exercise it much (and by pure chance I heard several of my work colleagues saying the same thing today). Do I need hand-writing in modern life? Not really, not for anything crucial.

I don’t think it’s just me. On my commuting journeys I see people reading all kinds of things – newspapers, books, magazines, Kindles, phones, tablets and so on. I really cannot remember the last time I saw somebody reading a piece of hand-written material on the tube.

Now, to set against that, I have friends and relatives for whom the act of writing is still important. They would say that the nature of the writing surface and the writing implement – pencil, biro, fountain pen – are important ingredients, and that bodily engagement with the process conveys something extra than simply the production of letters. Emphasis and emotion are easier to impart – they say – when you are personally fashioning the outcome. To me, this seems simply a temporary problem of the tools we are using, but we shall see.

Looking ahead, I cannot imagine a time when reading skills won’t be necessary – there are far too many situations where you have to pore over things in detail, review what was written a few chapters back, compare one thing against another, or just enjoy the artistry with which the text had been put together. Just to recognise which letter to tap or click requires that I be able to read. But hand-writing? I’m not at all sure this will survive much longer.

Perhaps a time will come when teaching institutions will not consider it worth while investing long periods of time in getting children’s hand-writing to an acceptable standard – after all, pieces of quality writing can be generated by several other means.

Great post Richard. I love writing – much prefer it to typing. I made a point of writing all my notes for my 1st book with a fountain pen and am doing the same with my 2nd book. I find I remember more when I have actually written it down, rather than when I’ve typed it.

Way back in school we had to write with fountain pen – no nasty biros or the like, though in sixth form then some latitude was allowed – and a very messy business it became sometimes. But I have friends who, like you, prefer real pen and ink.