Today’s element is energy – a simple word that contains a wide variety of meanings. Long ago, energy meant simply getting enough heat to keep a human community warm through winter. Although humans may well have originated from Africa, they scattered across the face of the Earth at an early stage. A Russian paper just this week in Science strongly suggests that humans were hunting well north of the Arctic Circle around 45,000 years ago – seems we can adapt ourselves to all manner of inhospitable climates!

But as time went by, energy meant other things. We needed energy not just to keep warm or cook food, but also for metal work. The required temperatures steadily rose – around 1000° C or so for copper and bronze, or about 1500° for iron. And as well as that, we wanted energy to extend the day length by giving light to continue tasks past sunset – increasingly important the further we strayed from the equator. All this energy had to come from somewhere, and human societies devoted an increasing proportion of their time to extracting the raw materials – wood, coal, oil and so on, all ultimately from long-dead living things. And at different times and places we have also derived energy from the effort of animals and slaves, the movements of water or wind, steam, the sun, chemical and radioactive changes in matter, and so on.

All of these things have an impact on the environment. We often think about the impact of manufacturing use – like England’s New Forest being cut down to provide raw material for the Royal Navy – but simple generation of energy soaks up a very large amount. We switched from wood to coal here in England partly because it is a more efficient source of heat, but partly also because we were burning trees way faster than they could grow, and were running short of them. Here’s a visual way of looking at our use of energy – this chart tells us that the consumption per person of energy for all purposes is over 100 times what it was for our remote ancestors. When you also factor in the huge numerical increase in the human population, it is clear that we are extremely energy hungry.

My historical novels are set about half way along this chart – energy was being used for all kinds of purposes, but could be met largely from local sources without need for major imports. Environmental impact was largely for other reasons – for example the hill country of Canaan used to be heavily wooded, but almost all of it was cleared in the early Iron Age to make way for larger settlements.

It’s no secret that managing our demand for energy, and the consequences of that demand in terms of unwanted heat, pollution, exhaustion of natural resources, and so on, is a major problem facing us today. Not only that, but the volumes of raw materials we need, and the limited parts of the earth’s surface which hold them, mean that large parts of our transport network have to be given over just to transporting energy-making materials.

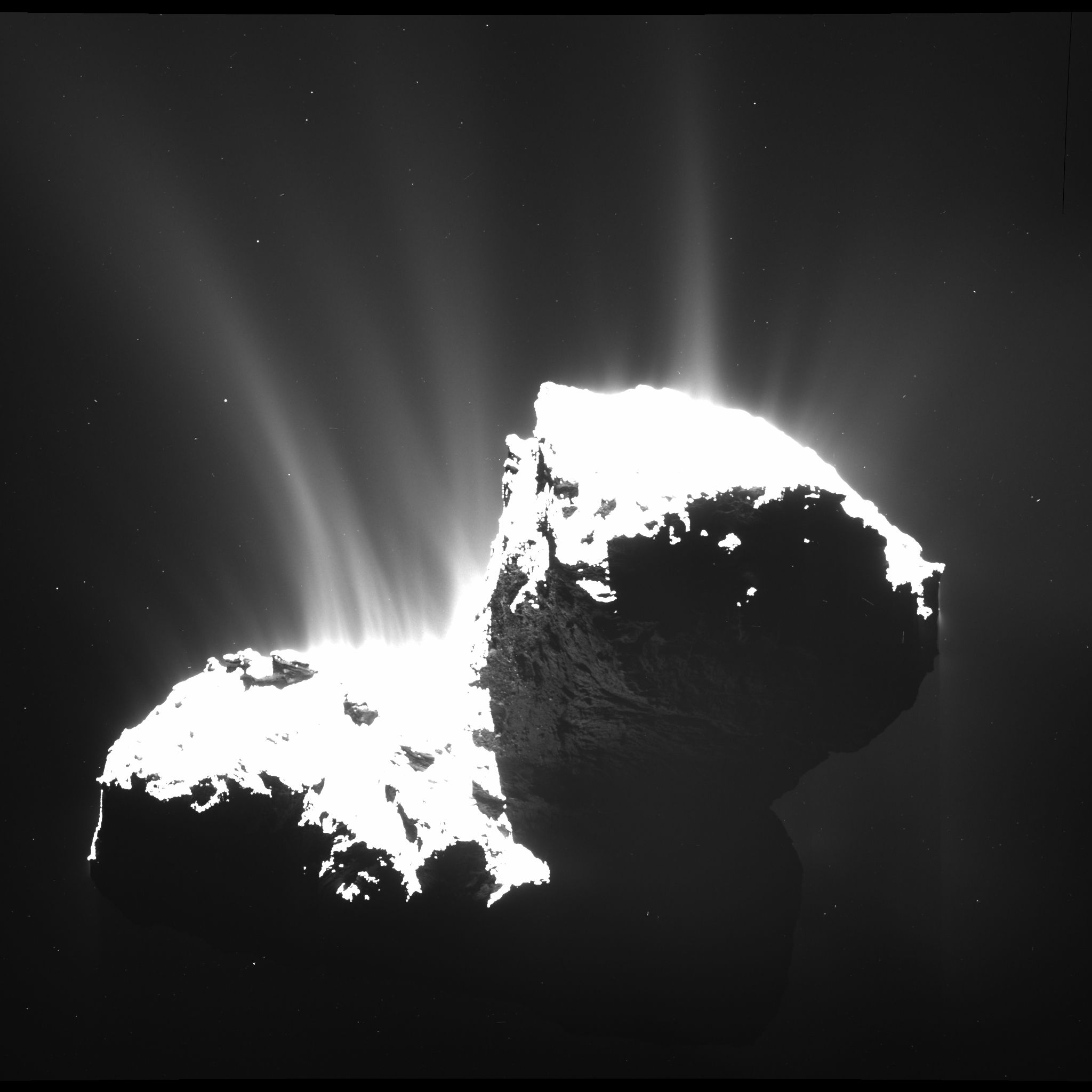

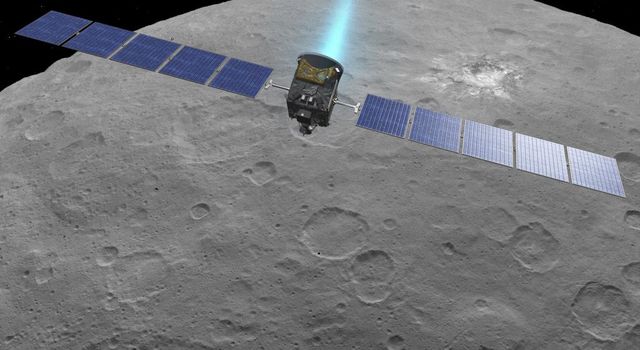

When you look out into space, and the speculative colonisation of the solar system of Far from the Spaceports, we face a different set of problems, By now, we are all used to the sight of solar panels capturing the sun’s radiation and powering probes and satellites. But as you travel further away from the sun, the quantity of light drops off rapidly. At the orbit of Mars, there is rather less than half the intensity as there is close to Earth. At Jupiter, there is less than 4%. At Pluto’s closest approach, the figure is under 0.1%.

So, even with perfect capture, the area needed increases to rather ridiculous proportions as you travel further from the sun. The current record-holder for most distant spacecraft still using solar power is NASAs Juno vessel, in its closing stages of approaching Jupiter. Juno has 3 massive solar panels, with a combined area of about 50 square meters (roughly the front face of a house) which in Jupiter orbit will generate a mere 400 watts – a handful of light bulbs. The same area in Earth’s orbit would generate about 14 kilowatts. Further out – Saturn and the still more distant planets – we would have to rely on other kinds of generator since the intensity of sunlight is too weak. Or, to put the same matter a different way, the area of solar panels required would be prohibitively large. Right now, the favoured method is a nifty gadget called an RTG, which uses the heat generated by radioactive decay (quite different from a nuclear power plant, which uses the decay products themselves). The RTG units on Voyager 1 and 2 started life in 1977 at just short of 40kg (about what you might carry onto a plane), and are expected to drop below feasible operating levels by about 2025.

Basically, energy is always going to be a problem, wherever we go. The things we like, and that we like to do, are hungry for energy. Another of those top-of-the-list items, as and when we settle out among the asteroids, the moons of Jupiter or Saturn, or anywhere else, will be to secure a reliable source of energy.

Next time… food