Last week we looked at how views of Venus had changed in fiction: this time it’s Mercury’s turn. Like Venus, Mercury is never visible far above the horizon – indeed, it never gets above 17 degrees here in London, less than half that of Venus. It’s another morning and evening star candidate, though far fainter than Venus, and far easier to miss unless viewing conditions are good. In classical times, Mercury was the swift messenger of the gods, presumably because of his elusive presence, rapid shift across the sky, and proximity to the sun.

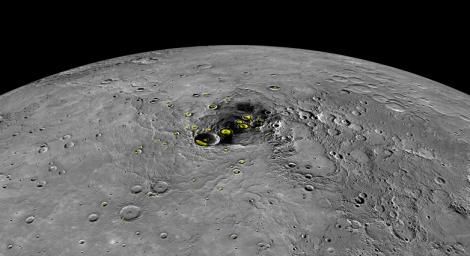

Once telescopic study of the planets began, it became obvious that Mercury was going to be pretty inhospitable. It orbits at just over 1/3 of the Earth-Sun distance, has virtually no atmosphere, and experiences temperatures up to 450°C on the sunlit side (oddly, that is much the same as Venus, but for quite different reasons). Lead, zinc, and a whole bunch of other metals would melt under these conditions. Bizarrely, even here, there are a few shady places where water ice can still exist on the surface – water is one of the most persistent and universal features of our solar system.

For a long time it was thought that Mercury was tidally locked, always showing the same face to the sun. More recently we have found that this is not the case – Mercury’s day is 59 Earth days, while its year is 88 Earth days – 2 Mercury years contain just 3 Mercury days. The combination means that every time Mercury is closest to the Earth, we see the same surface features… one of those mutual rhythms which appear all over the solar system.

You’d think that fiction writers would struggle to place a story on Mercury, but numerous people have tried. ER Eddison, in his fantasy series starting with The Worm Ouroboros, located his events there – though he was singularly unconcerned with the real planet, and simply used “Mercury” as a handy, mysterious location, at which very Earthlike deeds took place. In his writing, Mercury is simply an elsewhere location outside his readers’ everyday life.

When it was thought that Mercury was tidally locked, several authors assumed that humans would build a settlement somewhere on the dividing line between unbearable heat and implacable cold. Plots often revolved around the (supposed) vast difference between light and dark sides. For example, Hugh Walters’ Mission to Mercury supposes that the extreme heat (and cold) would lead to different personality problems (interestingly, this book also features another occasional trope, that of identical twins who can communicate telepathically).

The discovery that Mercury actually does rotate put paid to the idea of a temperate band, leaving us with a largely undesirable planet! It is a long way “down” in the sun’s gravity well, so needs a disproportionate amount of fuel to get there and back. Unless there turns out to be plentiful and easily accessed resources of some kind – gloopy patches of pure platinum, or some such – then it’s hard to see why it would ever be more than a solar research base. Authors and technologists have contemplated terraforming Mars (of which more next time) or Venus (AE van Vogt suggested that it could provide an exotic home for the elite in The World of Null-A) – I can’t think of anyone who has suggested terraforming Mercury! Kim Stanley Robinson, in several novels and short stories, suggested one solution would be a city built on rails which very slowly moved around the planet and hence always stayed in the twilight zone.

In fiction, it has become, and most likely will remain, a hostile place which might contain or provoke mystery. And in keeping with that, I’m not (currently) planning any books in my science fiction series which are set there.

Finally, you’re not (quite) too late to take advantage of the giveaway offer on the audio version of Half Sick of Shadows – details in a former blog post…