A shorter blog today focusing specifically on navigation. I mentioned before that there were two different ways of navigating through the sections of an ebook, and this little post will focus on how they work. The two methods appear differently in the book – the HTML contents page is part of the regular page flow of the book, and the NCX navigation is outside of the pages, as we’ll see later.

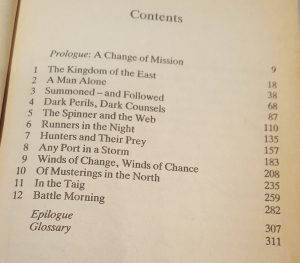

It’s an area where ebooks behave quite differently to print versions. If you have a table of contents (TOC) in a print book it’s essentially another piece of static text, listing page numbers to turn to. Nonfiction books frequently have other similar lists such as tables or pictures, but I’ll be focusing only on section navigation – usually chapters but potentially other significant divisions. In an ebook this changes from a simple static list into a dynamic means of navigation.

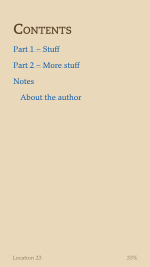

Let’s take the HTML contents first. It looks essentially the same as the old print TOC, except that the page numbers are omitted (since they have no real meaning) and are replaced by dynamic links. Tap the link and you go to the corresponding location. They look just like links in a web page, for the very good reason that this is exactly what they are!

So the first step is to construct your HTML contents list, for which you need to know both the visible text – “Chapter 1”, perhaps – and the target location. Authors who use Word or a similar tool can usually generate this quite quickly, while those of us who work directly with source files have the easy task of inserting the anchor targets by hand. It’s entirely up to you how you style and structure your contents page – maybe it makes sense to have main parts and subsections, with the latter visually indented. It’s your choice.

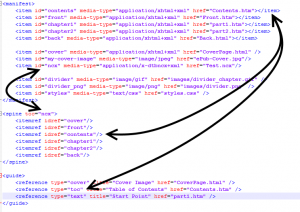

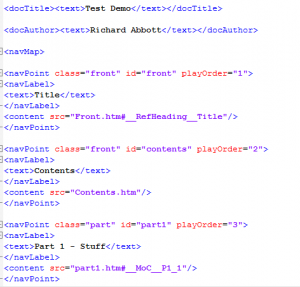

The NCX navigation is a bit different. It’s a separate file, and the pairing of visible text and target link is done by means of an XML files of a specific structure. Again. some commercial software will be able to generate this for you, using the HTML TOC as a starting point, but it’s as well to know what it is doing for you. Conventionally the two lists of contents mirror each other, but this doesn’t have to be the case. For example, it might suit you better to have the HTML version with an exhaustive list, and the NCX version with just a subset. It’s up to you. However, the presence of NCX navigation in some form is a requirement of Amazon’s, sufficiently so that they reserve the right to fail validation if it’s not present. And it’s a mandatory part of the epub specifications, and a package will fail epubcheck if NCX is missing. You’ll get an error message like this:

Validating using EPUB version 2.0.1 rules.

ERROR(RSC-005): C:/Users/Richard/Dropbox/Poems/test/Test.epub/Test_epub.opf(39,8): Error while parsing file ‘element “spine” missing required attribute “toc”‘.

ERROR(NCX-002): C:/Users/Richard/Dropbox/Poems/test/Test.epub/Test_epub.opf(-1,-1): toc attribute was not found on the spine element.

Of course, if you don’t check for validation, or if you just use Kindlegen without being cautious, you will end up with an epub or Kindle mobi file that you can ship… it will just be lacking an important feature.

Interestingly, you don’t get an error if you omit the HTML TOC – so long as everything else is in order, your epub file will pass validation just fine. This is the opposite of what folk who are used to print books might guess, but it reflects the relative importance of NCX and HTML contents tables in an ebook.

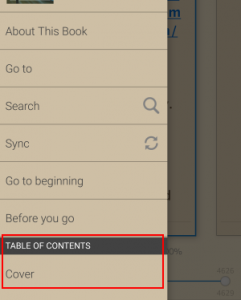

So what exactly do they each do? The main purpose of the HTML version is clear – it sits at the front of the book so that people can jump directly to whatever chapter they want. It would do this even if you just included the file in the spine listing. But if you are careful to specify its role in the OPF file, it also enables a link in the overall Kindle (or epub) navigation. This way the user can jump straight to the TOC from anywhere.

The NCX navigation enables the rest of this “Go To” menu. If it’s missing, or incorrectly hooked up in the OPF file, the navigation will be missing, and you are leaving your readers struggling to work out how to flick easily to and fro. On older Kindles, there were little hardware buttons (either on the side of the casing or marked with little arrows on the front) which would go stepwise forwards and backwards through the NCX entries.

So that’s it for the two kinds of navigation. They’re easy to include, they add considerably to the user experience, and in one way or another are considered essential.