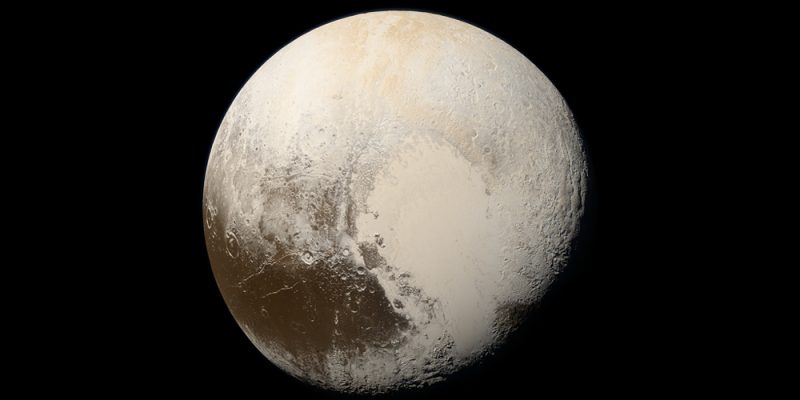

I’ve blogged before about how Pluto – orbiting between 30 and 50 times as far from the sun as our Earth, and so receiving at best one thousandth of the radiant energy from the Sun – has proved to be a hugely interesting place to explore. This is in stark contrast with old science-fiction books, which dismissed Pluto as a featureless frozen lump with no real attraction to spacefarers. The data returning from NASA’s New Horizons probe, which is still being pored over and analysed, has changed all that, revealing Pluto and its major moon, Charon, as fascinating worlds in their own right.

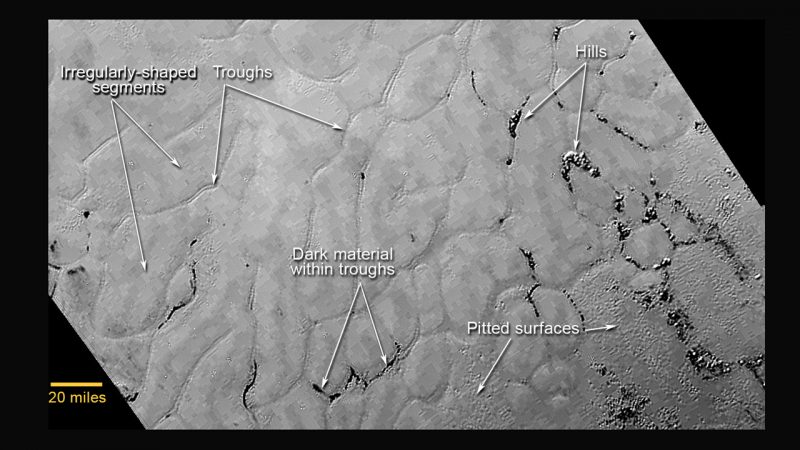

There has been some evidence before now, that Pluto might have an ocean below its surface. For example, there were pictures like the one below, showing that the smooth region of Sputnik Planitia (the white region shown above, just right of centre) has surface details which look for all the world like an ice skin over liquid. In addition, the layer of ice across the surface is thinner here than the average across Pluto.

Now, several other bodies out in the distant reaches of the solar system do have oceans – the best known being Europa – but typically these are on moons orbiting one or other of the giant planets. Europa, for example, is Jupiter’s fourth-largest moon. In these cases, the gravity of the planet causes tides which constantly flex the moon. This flexing in turn causes internal heat, and so the liquid remains liquid rather than freezing solid. Pluto has no such planet to orbit around, and the mechanism by which a sub-surface ocean might stay liquid was unknown.

Two recent pieces of research have strengthened the idea, and provided a suggestion of just how the ocean might stay liquid. First, scientists studying the part of Pluto diametrically opposite to Sputnik Planitia noticed black “ripples” of rock where the surface had been thrown into a turmoil which it is hard to imagine. According to the survey, another rock, about 250 miles across, collided with Pluto some long time ago, creating the Sputnik region. The shock waves then travelled both around Pluto’s surface and through its interior, ending up focused on the opposite side as though through a lens. Such shock waves travel fast through a planet’s rocky core, more slowly around the surface layer, and slower still through a sub-surface ocean. The role of the ocean is clear: for these different types of wave to coincide on the opposite side, the fast transit through the core is balanced with the slow one through liquid, ending up at the target at the same time as the medium ones around the surface.

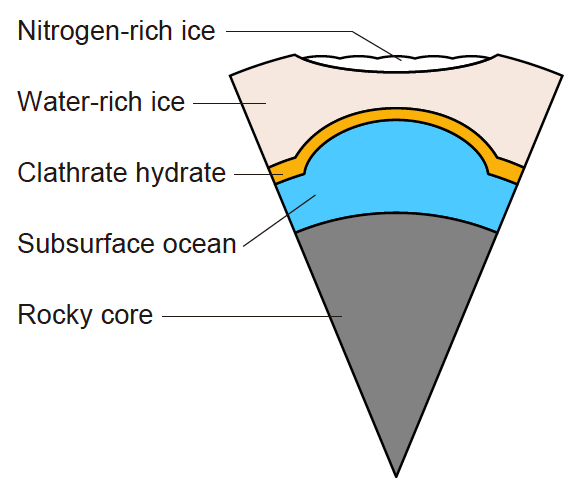

So, how would the liquid remain liquid over long spans of time? The clue here comes from some computer simulations made by a joint Japanese-American team, in which they study the most likely scenario which remains consistent with other facts we know about Pluto. They suggest that a thin layer of chemicals called hydrates (crystalline solids resembling water ice) would act as an insulating blanket, keeping the liquid warm enough not to freeze. The hydrate layer is based on methane, which would rise up from Pluto’s core and collect at this level of the planet.

An ocean on (or, rather, under) Pluto is surely one of the least expected outcomes of the New Horizons’ observations. As we find steadily larger numbers of exoplanets beyond our own solar system, it is worth wondering – if Pluto of all places can maintain an ocean, then how many more ocean planets and moons might there be out there?

Meanwhile, the release date for my next novel, The Liminal Zone, is getting closer. It’s the next in the Far from the Spaceports series, but set a couple of decades later, when the joint exploration of the solar system by people and AI personas has moved beyond the asteroid belt all the way out to Pluto’s moon Charon…