Last weekend, a whole bunch of people, including a number of my online friends, have been remembering and reenacting the events surrounding the Battle of Hastings – 1066 and All That. It so happens that everyone I know who was at Hastings the other day favoured the Saxon side, from which perspective Harold is a fallen hero, who came so close to repelling the invaders in the south as well as the north. But I suppose that a great many of the participants took the Norman side, and so found themselves once again victorious.

In fact, most people I know prefer the Saxons, and harbour a deep-seated wish that things had gone differently. Perhaps this comes from a desire to cheer on the underdog, or from hearing about how viciously the Normans set about securing the land they had claimed (especially in the north). But I suspect it is also because we were brought up on tales of Robin Hood and his Merrie Men, striving as disenfranchised and downtrodden Saxons against their wicked and uncouth Norman overlords.

I have to admit that, personally, I struggle to see the Saxons as unequivocally the nice guys in our history. My own historical preference is earlier, often swimming in the uncertainty and veiled mystery of times before the written word gave us its particular perspective. And from my view, the Saxons (and Angles, etc) are new arrivals who themselves had claimed a new land by often violent methods. The tales of Arthur and his Companions, stripped of their courtly Medieval topcoat, tell us of a time when British and Welsh leaders tried to protect their homes from wave after wave of incoming aggressors.

Ultimately their stand was a failure – from south to north the Saxons defeated and occupied British land, and the points of resistance were only sandcastles in a rising tide. Perhaps the last to fall was Dunmail, in what we now call Cumbria. As this last king of the British lost his last battle, his last few loyal men took his crown and cast it into Grizedale Tarn, so the new usurper would not have the satisfaction of claiming it. Like Arthur, the promise is that Dunmail will – one day – arise again to claim his crown and kingdom.

So – making what I suspect are controversial statements – I kind of feel that there was something karmic in the events of 1066. The Saxons had arrived and pushed aside the earlier occupants, and now something very similar was happening to them.

Now, arrivals into a country are a curious thing. It’s worth thinking about how we reconstruct what happened. In the past we have had to rely on written perspectives, often put down on paper, papyrus, or clay many years later by the winners or their ancestors. Or we look at archaeological remains, which by their nature can only say so much about their owners. Did the same culture adopt new artefacts quite suddenly? Or did a new culture simply reuse the same things as their predecessors? Nowadays we can have a bit more insight from DNA testing, and the outcome of this has sometimes supported and sometimes challenged prior expectation. More of that later.

There are basically two ways that new arrivals interact with those people already there. Sometimes there is violent displacement of the old by the new. This seems to have happened in Bronze Age Britain, where there is hardly any genetic continuity between the Beaker People and their Neolithic precursors – the great stone monument builders have left almost nothing of their genetics throughout most of Britain. This DNA result rather overturned the prior thinking that the change represented a peaceful transfer of ideas.

Other times the old and new quietly absorb each other and are enriched by the process, playing out on a national or regional level the process of human reproduction, with all its delights and difficulties. Newcomers might arrive for all kinds of reasons, martial or peaceful, but after a few years one finds a fusion of the two emerging – a child of both originals.

Now, at the time of arrival, nobody knows what will happen, and it’s natural for the current inhabitants to fear and deride the incoming hoard. So the Saxons did to the Normans.. so the Britons did to the Saxons… so the Neoliths did to the Beaker People… and no doubt so the Neanderthals did to the Homo Sapiens clans. We still see this played out today, as nationalist politics finds innovative ways to arouse anxiety about “the other”. They’ll take our jobs… they’ll impose their religion… they’re not like us… slogans about “the other” can be found in pretty much every part of our world, fuelled by migrations and flights from war and famine. Personally I remain optimistic, and look for the creative fusion of cultures rather than the catastrophic collision. But looking back at history, it takes effort to find creativity, and we humans don’t always manage it.

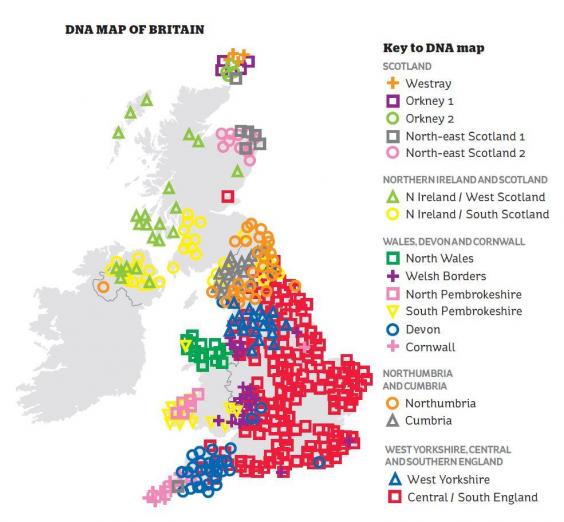

Going back to DNA, there are still limitations. We can now – tentatively, and extrapolating from individual cases – identify where intercourse has combined the heredity of two cultures. So we know that the DNA map of Britain correlates pretty well with some historical events, and not with others. We know that pretty much all humans outside Africa have a significant percentage of Neanderthal DNA. We know that a teenage girl’s finger from Siberia shows her to be the child of one Neanderthal parent and one Denisovan parent, some 90,000 years ago. But what we don’t know is the circumstances of the intercourse. Was it a socially sanctioned event, even a personally consenting one? Or was it something darker, the result of forced prostitution or rape? DNA cannot tell us, but that’s the kind of detail we would like in order to uncover the interactions of peoples. It’s one of the great anxieties of mankind – do the newcomers arrive in peace or war?