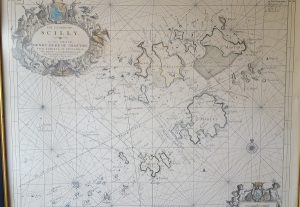

Today’s topic is – once again – inspired by an experience on the Scilly Isles. It has to do with how things look different from one point of view than they do from another. If you were going to navigate between the islands – say from Bryher round to St Martin’s – then the chances are you’d pull out a map. If you were feeling particularly cautious, or you were going in a larger boat which drew more water, maybe you’d go up a grade and get yourself a chart with underwater depths plotted. Coupled with some knowledge of the tide, you could then plot out a course.

Now if you also had a GPS navigation system, in principle you could then hand over the course to that, sit back, and enjoy the journey with no more effort. But if you didn’t have that, and you were reliant on personally converting all that map work into movements of the tiller, you’d find that it is rather more tricky than it looks.

A map is a top-down view of the world – the sort of thing you would see if you were flying. But out on the water you get a completely different perspective. You are looking along the (reasonably) flat surface of the water, seeing the sides of islands and rocks as they project up from that surface. Some things – perhaps your destination – are hidden behind other ones. Some things which look close together are actually far apart, having been brought together by visual accident. A passage between two rocks might appear wide and easy on your chart, but narrow and problematic on the water, since it calls for careful wiggling at key moments.

Now, of course, this was the norm for navigation throughout our history until very recently, and goes a long way to explaining why the profession of pilot was so important. The pilot knew his waters, and how to navigate ships of different sizes through them at different states of the tide – or indeed not to make the attempt until the tide turned.

Now, maps and charts to help navigation have been around for quite a long time – several centuries, at least. But a pilot in action was not so interested in the top down view given by a chart. What he wanted – needed – to know was the direction to steer in at any point. And this was done, by and large, by means of lines of sight. Certainly pilots necessarily built up a vast store of information of local conditions in all kinds of weather and tide. But the key to their navigation was the index of knowledge which knew that by lining up particular landmarks one behind the other, and trusting these remote guidelines over local phenomena, a difficult voyage could be broken down into a series of simple legs.

Each sight line gives you a stage in your journey: each journey consists of a chain of such guidelines. Arthur Ransome used this idea in Swallows and Amazons, where a navigation line was set up by visible marks in daytime, or lanterns after dark. John says: “This [stump marked with white cross] is one of the marks, and the other is that tree with a fork in it… come into the harbour without bothering about the rocks by keeping those two in line”. In this way they could easily get in and put of the harbour on Wildcat Island. The pilot’s job was basically the same, but upscaled to a much larger region and a hugely more complex set of navigation tasks.

But it is not just navigation on the water which has this difficulty. When we look up at the night sky, at stars and planets, we are looking at objects scattered through a vast three-dimensional space, as though they were arranged on the surface of a sphere. Extremely distant objects are pressed together, and small nearby ones can hide much larger further-away ones – as in this solar eclipse. And although changing tides are not a problem in space, things are moving at different speeds, and if you are trying to navigate – say – from one of Jupiter’s moons down to Mars, you have to take into account the change of location which will happen in the meantime. Human pilots still ply their trade in many parts of the world, and although they are usually supported by electronic backup, it still calls for in-depth familiarity with their coast, and day-by-day assessments of change. I wonder if the same will be true if and when we move into space?

You still get pilots now and then. Last year I went on cruise around Australia’s ‘Top End’, and a pilot boarded the cruise ship – a humungous vessel – to get us through the Great Barrier Reef.

Yes indeed, particular places still require them, especially for some kinds of vessel. Seeing the Great Barrier Reef from the water must have been fantastic!