The solar system is a big place, and journey time is a big issue with present technology. The Apollo capsules took just over three days to go from the Earth to the Moon, and the several current proposals for sending people to Mars involve months of travel time. The New Horizons probe which recently flew past Pluto took the better part of ten years to arrive there after leaving Earth.

Now, for narrative purposes in Far from the Spaceports, I wanted journeys between planets to last weeks rather than months or years. This gives a reasonable sense of remoteness, without the drawback of having settlements separated so far from each other as to make meaningful interaction virtually impossible.

Almost all contemporary space journeys are based on the principle of critical burn points. The vehicle performs a small number of high energy rocket firing sessions at key stages of the trip, typically at start and end, with smaller mid-journey corrections. The rest of the time is spent in free fall, unpowered. This saves fuel, and is the only feasible journey choice for chemically based rockets.

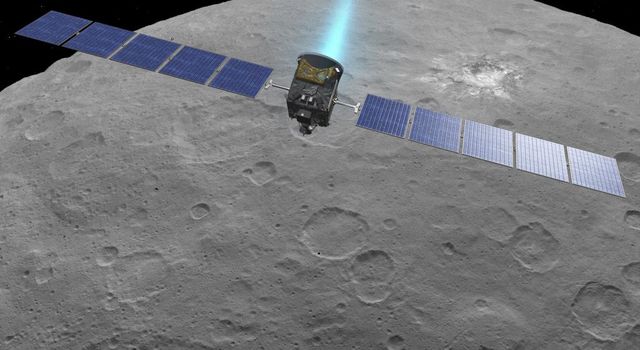

Here, for fun, is a NASA artist’s impression of the Dawn probe using its ion drive near Ceres.

But this occasional burn pattern also means that speed is limited, especially for human travellers. A person can only withstand acceleration of a few multiples of Earth’s gravity, and the total change in speed is therefore limited. You are stuck at whatever speed your short burns can achieve. Logically, it is far better, once away from the immediate vicinity of Earth, to maintain a low acceleration rate all the time. This doesn’t appear to do much over the course of a few seconds, but the cumulative effect adds up to something quite impressive. There have been experiments with this already, using a technology called the ion drive, of which more later.

For the moment just assume that there is a technology able to drive a spaceship with an acceleration of 1/20 the surface gravity of Earth. That gives the occupants a sense of up and down, and generally makes life easier. The recent film The Martian, following from similar ideas in 2001, used a rotating wheel idea to give a kind of pseudo-gravity to the astronauts, but their engine design was on the current occasional burn pattern. But if you had a drive which could be always on at a low level, then the quickest journey time to some remote point is to accelerate at constant rate to the half-way point, and then flip over and decelerate the rest of the journey. With that drive and flight plan, the average Earth-Mars trip takes about a month (just two weeks at the point where the orbits bring the planets closest together). The trip out to the asteroid belt takes four or five weeks, and a trip to Pluto about 4 months. Nicely in the range of what I want in a story.

What about reality? NASA has trialled ion drives on a couple of small probes, notably the Dawn mission which travelled to two destinations in the asteroid belt – the giant asteroid Vesta and the dwarf planet Ceres. Currently it is still in orbit around Ceres sending back scientific data. Dawn did not burn its ion drive engines full time, but it did trial them for blocks of hundreds of days at a time. Using this regime, Dawn took around four years to reach Vesta, having travelled inwards towards the sun first to acquire a gravity assist from Venus. After some science work at Vesta, Dawn took about two more years to migrate to Ceres. That’s longer than I want for the book, but it’s a whole lot better than just coasting there after a high-energy burn leaving Earth orbit.

In comparative terms, Dawn achieved an acceleration of around 1/100,000 that of Earth’s gravity, which is roughly equivalent to going from stationary to 60 miles per hour in four days (!). Even at such a low value, Dawn currently holds the speed record for spaceships sent out from Earth, with maximum speed around 11,500 meters per second. I am assuming that advances in technology bring that up to 1/20 gravity, which leads to a top speed around 130,000 m/s. I feel those are credible goals for technological advance of the hardware, given that I am also assuming that we have the ability and motivation to establish settlements on various rather inhospitable locations throughout the solar system.

Now, the actual distances between planets vary considerably depending whereabouts in their orbits each of them are – for example the Mars-Ceres trip can take anywhere between 20 and nearly 40 days with this engine. But the main thing, and the one I really wanted, was that you can go places within a month or so.

One thought on “Distance and transportation in Far from the Spaceports”