Time is a funny thing, especially as regards our perception of the flow of time. The same objectively-measured period of time can seem unbearably slow to one person, and disappointingly fast to the next. But fundamentally, our perception of time has been fashioned by generations of human and pre-human ancestors growing up on planet Earth.

We have become very deeply, viscerally accustomed to the various time rhythms of this planet – the 24-hour light dark cycle which gives us days, the 28-day lunar cycle which gives us months, and the 365-day solar cycle which gives us years. There are, of course, longer cycles still, such as the 18-year lunar rising pattern – our prehistoric ancestors seem to have been aware of this, though most of us today have forgotten it. Living anywhere on the surface of the Earth other than the extreme polar regions, all life is given, and responds to, days, months, and years.

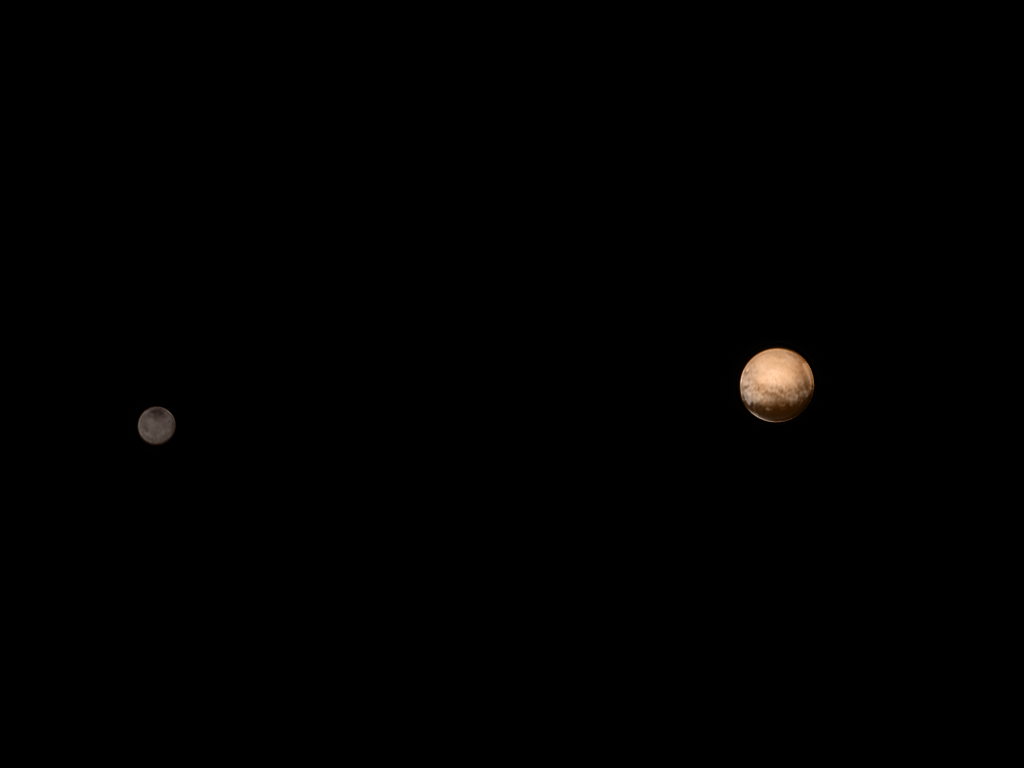

So one of the questions I posed myself while writing The Liminal Zone was, what would life be like if those rhythms were absent? Pluto’s moon Charon doesn’t have this range of patterns. There is a cycle of about a week, during which Pluto and Charon revolve around their common gravitational centre. As they do this, the light from the distant sun shifts to give light and darkness – so a “day” is about a week on Charon. They are tidally locked to each other, presenting the same face to their partner just as our Moon does to us, so that the “day” and the “month” are the same. But beyond that, there is no natural cycle for future inhabitants to shape themselves around until you get to Pluto’s orbit around the sun – 248 Earth years long.

How would this absence of multiple cycles affect human experience out there? Right now, the short answer is that we do not know. I imagine that, at least at first, occupants would retain a nominal Earth-based cycle of 24-hour days, with weeks, months and years built up from there. But on some level, I suspect that the missing natural cues for these cycles would start to weigh on us.

Some readers of The Liminal Zone have commented that there is a slightly timeless aspect to the characters in the novel. They respond to, and act on, slowly changing patterns rather than the swift passage of events. An impression made at first meeting tends to freeze into a lasting reaction. If so, then this is exactly what I wanted. I believe that the absence of natural months and years (in the way we are intimately familiar with, here on Earth) would, little by little, soak into the lives and psyches of those people. In the end, the vast slowness of life in the Kuiper Belt, the liminal zone of the whole solar system, would prevail. As Elaine, one of the central characters, says of herself, “There is nothing more important than the recognition of patterns.” The hurry and bustle of weeks, days, hours, minutes, seconds, has yielded in her to an appreciation of how patterns once experienced tend to repeat themselves in different ways into the future. For her, those patterns are the stationary points in the apparent disorder of the cosmos: they are the situations she likes to recognise and gravitate towards.