This is the first of two posts in which I talk about some of the major things I took away from the recent Future Decoded conference here in London. Each year they try to pick out some tech trends which they reckon will be important in the next few years.

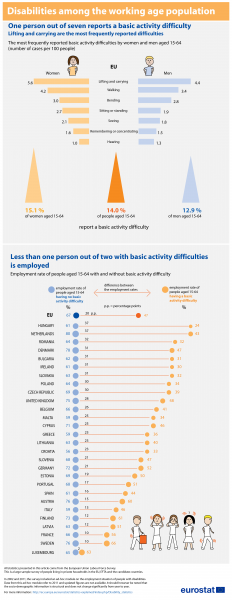

This week’s theme is to do with stuff which is available now, or in the immediate future. And the first topic is assisting users. Approximately one person in six in the world is considered disabled in some way, whether from birth or through accident or illness (according to a recent WHO report). That’s about about a billion people in total. Technology ought to be able to assist, but often has failed to do so. Now a variety of assistance technologies have been around for a while – the years-old alt text in images was a step in that direction – but Windows 10 has a whole raft of such support.

Now, I am well aware that lots of people don’t like Win 10 as an operating system, but this showed it at its best. When you get to see a person blind from birth able to use social media, and a lad with cerebral palsy pursuing a career as an author, it doesn’t need a lot of sales hype. Or a programmer who lost use of all four limbs in an accident, writing lines of code live in the presentation using a mixture of Cortana’s voice control plus an on-screen keyboard triggered by eye movement. Not to mention that the face recognition login feature provided his first opportunity for privacy since the accident, as noone else had to know his password.

But the trend goes beyond disabilities of a permanent kind – most of us have what you might call situational limitations at various times. Maybe we’re temporarily bed-ridden through illness. Maybe we’re simply one-handed through carrying an infant around. Whatever the specific reason, all the big tech companies are looking for ways to make such situations more easily managed.

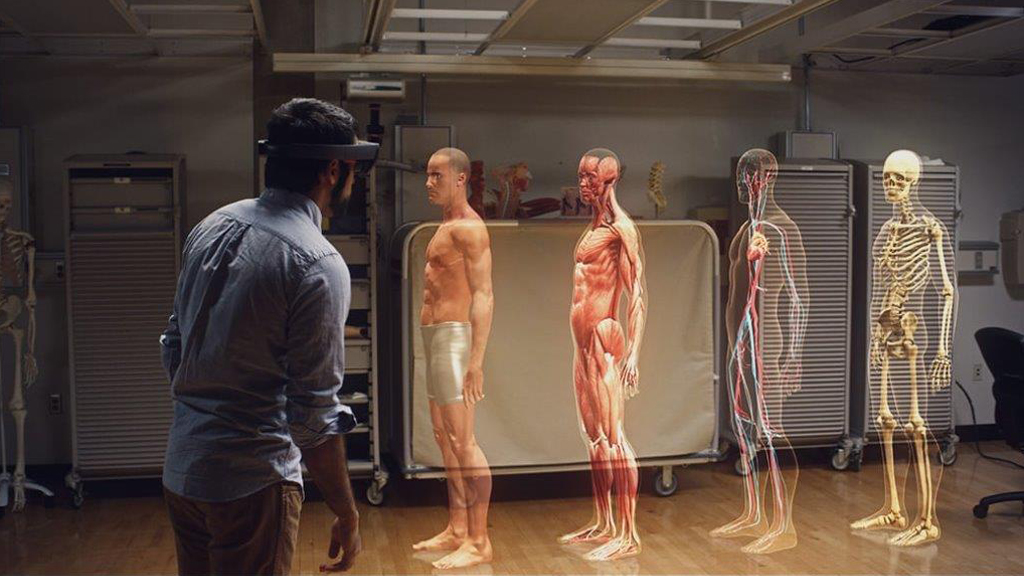

Another big trend was augmented reality using 3d headsets. I suppose most of us think of these as gaming gimmicks, providing another way to escape the demands of life. But going round the exhibition pitches – most by third-party developers rather than Microsoft themselves – stall after stall was showing off the use of headsets in a working context.

Training was one of the big areas, with trainers and students blending reality and virtual image in order to learn skills or be immersed in key situations. We’ve been familiar with the idea of pilots training on flight simulators for years – now that same principle is being applied to medical students and emergency response teams, all the way through to mechanical engineers and carpet-layers. Nobody doubts that a real experience has a visceral quality lacking from what you get from a headset, but it has to be an advantage that trainees have had some exposure to rare but important cases.

This also applies to on-the-job work. A more experienced worker can “drop in” to supervise or enhance the work of a junior one without both of them being physically present. Or a human worker can direct a mechanical tool in hostile environments or disaster zones. Or possible solutions can be tried out without having to make up physical prototypes. You can imagine a kind of super-Skype meeting, with mixed real and virtual attendance. Or a better way to understand a set of data than just dumping it into a spreadsheet – why not treat it as a plot of land you can wander round and explore?

Now most of these have been explored in fiction several times, with both their positive and negative connotations. And I’m sure that a few of these will turn out to be things of the moment which don’t make it into everyday use. And right now the dinky headsets which make it all happen are too expensive to find in every house, or on everyone’s desk at work – unless you have a little over £2500 lying around doing nothing. But a lot of organisations are betting that there’ll be good use for the technology, and I guess the next five years will show us whether they’re right or wrong. Will these things stay as science fiction, or become part of the science of life?

So that’s this week – developments that are near-term and don’t represent a huge change in what we have right now. Next time I’ll be looking at things further ahead, and more speculative…